|

How to cite: García, O. J. (2024). Conceptions of Childhood in the Initial Training of Teachers: A Phenomenological Research Conducted in the Teacher Training Schools of the Department of Caldas, Colombia. Ánfora, 31 (57), 143 - 172 . https://doi.org/10.30854/anf.v31.n57.2024.1115 |

Omar Javier García Martínez2 https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6266-5652 CvLAC https://scienti.minciencias.gov.co/cvlac/visualizador/generarCurriculoCv.do?cod_rh=0001137441 Colombia

|

Objective: This article presents findings from broader research aimed at exploring the significance of complementary training programs at the Teacher Training Schools of the Department of Caldas in shaping the relationship between conceptions of childhood and pedagogy in teacher training. Methodology: A hermeneutic phenomenological methodology was employed, utilizing in-depth interviews, focus groups, and associative letters to investigate three groups of teachers from each of the four Teacher Training Schools sampled in Caldas. Results: The research findings elucidate the various conceptions of childhood that emerged from the experiences of teachers, shedding light on their significance within the context of teacher training programs. They are synthesized in categories. These categories encompass reduction to developmental stages, the invisibility of cultural change in modern childhood, and conceptions of contemporary childhoods. Conclusions: The findings underscore the significance of teachers' experiences in shaping their conceptions, rooted in their own childhoods. Furthermore, the research highlights the theoretical gaps in teacher training regarding the cultural shifts in contemporary childhoods and emphasizes their critical role in shaping pedagogical practices within teacher training institutions.

Keywords: conceptions of childhood; cognition; pedagogy; teacher training. (obtained from the Eric thesaurus).

Objetivo: este artículo es resultado de una investigación más amplia, cuyo objetivo fue develar el sentido que dan los maestros de los programas de formación complementaria de las Escuelas Normales Superiores del Departamento de Caldas a la relación entre las concepciones de infancia y pedagogía en la formación de maestros. Metodología: con una metodología fenomenológica hermenéutica, en la que se indagó con el uso de entrevistas en profundidad, grupos de enfoque y cartas asociativas en tres grupos de maestros para cada normal considerada dentro de la muestra de cuatro de Caldas. Resultados: los resultados de la investigación muestran las concepciones de infancia que emergen, y el sentido que tienen desde la experiencia de los maestros. Estas están sintetizadas en categorías vinculadas con la reducción a la etapa del desarrollo, la infancia moderna que invisibiliza el cambio cultural, y las concepciones de infancias contemporáneas. Conclusiones: se concluye el sentido de las experiencias vinculadas a la construcción de concepciones determinadas en la cognición de los maestros, construidas desde la propia niñez; así como las ausencias teóricas en la formación del profesorado sobre el cambio cultural de las infancias contemporáneas y su importancia en la configuración de las prácticas pedagógicas en las instituciones formadoras de maestros.

Palabras clave: concepciones de infancia; cognición; pedagogía; formación de maestros. (obtenidas del tesauro Eric) .

Objetivo: Este artigo é resultado de uma pesquisa mais ampla, cujo objetivo foi revelar o sentido atribuído pelos professores dos programas de formação complementar das Escolas Normais Superiores do Departamento de Caldas à relação entre as concepções de infância e pedagogia na formação de professores. Metodologia: Com uma metodologia fenomenológica hermenêutica, que investigou por meio de entrevistas em profundidade, grupos focais e cartas associativas em três grupos de professores para cada escola normal considerada dentro da amostra de quatro em Caldas. Resultados: Os resultados da pesquisa mostram as concepções de infância que emergem e o significado que têm a partir da experiência dos professores. Estas estão sintetizadas em categorias vinculadas com a redução à etapa do desenvolvimento, a infância moderna que invisibiliza a mudança cultural e as concepções de infâncias contemporâneas. Conclusões: Conclui-se o significado das experiências vinculadas à construção de concepções específicas na cognição dos professores, construídas desde a própria infância; assim como as ausências teóricas na formação do corpo docente sobre a mudança cultural das infâncias contemporâneas e sua importância na configuração das práticas pedagógicas nas instituições formadoras de professores.

Palavras-chave: concepções de infância; cognição; pedagogia; formação de professores. (obtidas do tesauro ERIC).

This article presents findings from doctoral research, focusing on the insights derived from meetings with three groups of teachers in training at the Teacher Training Schools (TTS). It specifically delves into the results pertaining to the first category that emerged from the research. The research centered on a fundamental issue within Teacher Training education concerning conceptions of childhood. These conceptions, often limited to the biological realm, overlook the socio-historical and philosophical dimensions that underpin contemporary childhood studies and the conceptualization of childhood. It is noteworthy to recognize the essential role of these conceptions in Teacher Training education, as they are inherent to its nature (Decree 1236, 2020) and pivotal for its ongoing development (de Guzmán, 1986).

The research problem also stems from a concern observed across various teacher training scenarios, where the academic study and theorization of childhood as a conceptual framework are often marginalized (García and Osorio, 2020; García, 2019), largely attributed to the delayed introduction of Piagetian theories in the country (Jiménez, 2011).

Conceptions are ideas that animate teachers' pedagogical practices. These concepts are shaped by experience and, therefore, are investigated through phenomenology. This approach opens the possibility of uncovering the essential structures of language that endow that experience with meaning. Through this approach, the researcher can identify the underlying semantic structures and construct detailed analyses that reveal a profound understanding of childhood conceptions.

Historical evidence suggests that the emergence of the concept of childhood triggered the development of several key institutions: Schools, pedagogical practices reflecting the focus on children's learning, and teacher training programs (Narodowski, 1999; Runge, 2017; Valencia, 2006; Álvarez-Uria & Varela, 1991). These categories have been mutually influenced ever since.

Currently, contemporary childhoods are separated from the ages of life and the biological view of development in stages. Childhood conceptions are intricately intertwined with the human condition, drawing from socio-historical and philosophical perspectives, and are crucially linked to advancements in the welfare state of nations. Within Caldas's normality-focused institutions, childhood is often narrowly construed as a mere stage of development. While clearly influenced by Piagetian studies, this focus on childhood as solely a developmental stage is not necessarily outdated or unimportant. However, it can limit our understanding of childhood by conflating distinct concepts such as childhood, early childhood, and Early Childhood Development (ECD) within a single framework.

Teachers' pedagogical practices reflect their underlying conceptions of childhood, shaped by their cognitive processing of experience. These conceptions, in turn, determine how teachers interact with children in the learning environment. Likewise, the work, conversation, and research scenarios of teachers in the Teacher Training Schools are influenced by cognition.

This qualitative study utilizes a mixed design approach, employing hermeneutic phenomenology (Ricoeur, 2002; Greimas, 1979; Trejo, 2012) alongside historiographic research techniques (Valencia, 2006). The research draws on both the conformational path approach (Valencia, 2006) and social representations theory (Abric, 2001). Three types of analysis were conducted: (1) Doxographic and etiological analysis of documentary sources (Valencia et al., 2002; García, 2006), (2) analysis of social practices and representations using Abric's (2001) free association method, and (3) structural discourse and semantic analysis inspired by Greimas (1979).

This study focused on the Teacher Training Schools of the Caldas department. Within each school, three groups of teachers formed the unit of analysis: 1) PFC Teachers (PFC stands for "Planes de Fomento a la Calidad," which translates to "Quality Enhancement Plans"), 2) PFC Students, and 3) Practice Teachers. A purposive sampling strategy (Hernández et al., 2006) was used, guided by criteria of feasibility, participant availability, and informed consent. The instruments used were associative letters, in-depth interviews and focus groups.

The method most closely aligned with the object of study and the research question is hermeneutic phenomenology, as it directly engages with the subjective experience of individuals through the analysis of phenomena such as the conception of childhood and pedagogy. It assigns value, significance, and meaning to the essence of the narrative, which is objectified, analyzed, and then synthesized by the researcher. Similarly, historical research techniques were utilized to analyze documentary information, along with social representation techniques to collect information directly from the living sources, namely the teachers.

The primary interest of the researcher was to uncover the meanings attributed by the interviewed teachers to childhood in relation to pedagogy and teacher training. These meanings emerge explicitly in the narration of the experience, which is personal and non-transferable. They are understandable through the possibility provided by phenomenology to unveil them by engaging in epoche, utilizing the paths of transcendental reduction of that experience, and generating interpretations until uncovering the structure of the conception and its relationship with the world evident to the researcher. At the same time, the subject's experience represents the lifeworld that is interconnected with that of others, as individuals make associations based on their relationships and interactions with each other. To elucidate and understand the association of conceptions, the associative letters of Abric (2001) were used as a tool to situate and explore the connections between experience and the formation of conceptions. Subsequently, further exploration was conducted through interviews and focus group discussions. Figure 1 depicts the methodological design, illustrating successive stages of data collection, analysis, and treatment of the information gathered in the TTS.

Teachers, through reflection on their own experiences, reconstruct their understanding of childhood and how it shapes their current conceptions. That is to say, the anecdotes, sought to uncover the origins of these conceptions, yield valuable insights when teachers share their own lived experiences, as illustrated below:

Conceptions are intricate, shaped by various moments of personal history that draw from different dimensions in their formation. For authors like Abelleira and Abelleira (2019), teachers construct their conceptions based on the teachings of certain reference authors encountered during their Teacher Training education, undergraduate studies, or postgraduate education, depending on their level of training. They also shape their conceptions through interactions with other educators and encounters with elements of language that have evolved into reflections, even if their origins are not clearly defined. For instance, exposure to media messages that convey ideas about children, childhood, or the concept of a child can influence their perspectives.

The ways of constructing the conception of childhood are multiple and refer to a diffuse panorama as far as academia is concerned. Some, from a scientific paradigm of science didactics, consider the conceptions in direct relation to the academic knowledge that the teacher should exhibit. However, some, more aligned with a pedagogical approach rooted in experiential learning, argue that these ideas shape teachers' thinking and actions (Zimmerman, 2004; Guzmán and Guevara, 2010; Zimmerman & Trabazo, 2015; García & Osorio, 2020), as evidenced by their discourse when recalling memories and experiences.

Conceptions are cognitively constructed through personal processes wherein, instead of acquiring conceptual knowledge, individuals structure knowledge based on experience. This integration of knowledge occurs across various and extensive periods of life, drawing from information gathered in diverse contexts. These conceptions allow or restrict learning and determine people's behaviors. In addition, they are ideas that animate ways of thinking and doing in everyday life, and this is not necessarily done explicitly (Zimmerman, 2004).

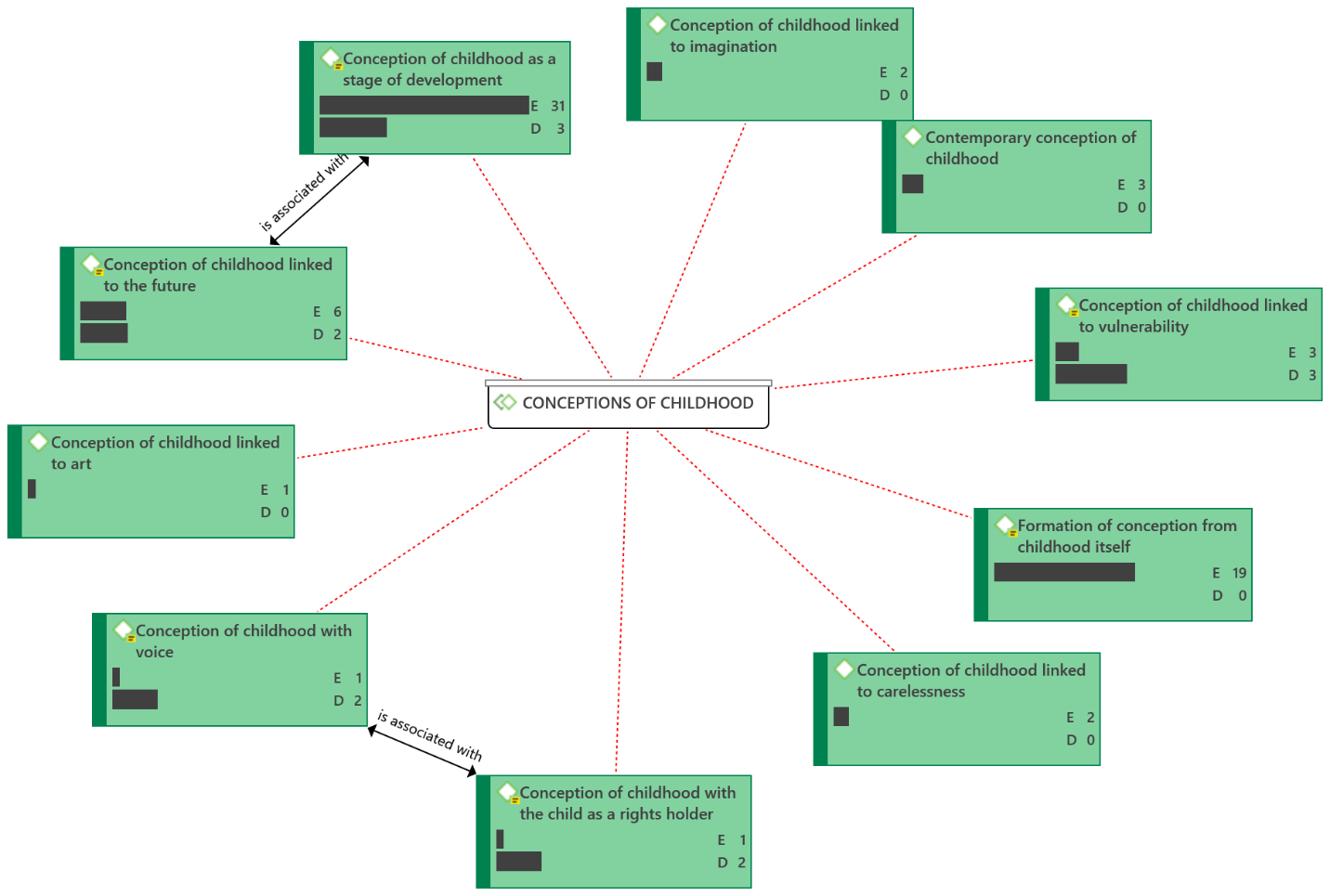

Hereinafter, one of the five semantic networks pertaining to the analysis of the results and their discussion is presented; the one called "the conceptions of childhood". Next, the synthesis of the process emerges as the conclusions of this study are presented, elucidating its connections and the profound intuitions of the researcher (Manen, 2016, p. 406).

When queried about childhood, educators in Teacher Training Schools often lean towards a developmental stage conception, often drawing from their studies or information received regarding Piagetian stages. This reduction of childhood particularly pertains to one of the age classifications, commonly referred to as early childhood, encompassing the period from birth to 5 or 6 years of age—a boundary that varies and is culturally arbitrary. Let's examine some instances from the interviews with the teachers, where they refer to this concept:

TTS 2MEO49: "[...] a stage of life during which the child develops skills that will later enable them to have greater capacity for functioning, such as social interaction, autonomy, self-awareness, and various cognitive abilities. (Personal communication, August 20, 2020, own translation).

The category that emerges from the analysis is the conception of childhood as a stage of development. This is the most frequent and recurrent way of naming and representing childhood in teachers' discourses. For them, childhood is a stage that comprises different periods, named in different ways. It is assumed, then, that there is syncretism between childhood and infancy, and between infancy and early and later childhood. When teachers consider this concept, they envision children in early childhood education from zero to five years of age and in primary basic education. That would be childhood understood as a stage of development.

Understanding it as a developmental stage, there is a strong link to developmental theories, discourses of growth and development, and early childhood development (ECD). This category of discourse is not isolated; it is interrelated with childhood linked to vulnerability, the future, carefreeness, imagination and art, and childhood with a voice, which are described below.

The conception of childhood configured in modernity has a character of division between the adult and child worlds, based on characteristics such as the need to play, lack of knowledge and experience, carefreeness, vulnerability, among others. The latter is recurrent in the speeches provided by the teachers in training at the Teacher Training Schools, who typically adopt this way of thinking about childhood. One of the anecdotes from the teachers' experiences illustrates this point.

TTS 2MPO19: "[...] it is a stage in which there is a lot of vulnerability. The child, because they are a child, is already vulnerable due to the things they have and the way they live, how they interact. There is always a vulnerability that is dependence, but they can also be exposed to other conditions such as physical vulnerabilities. For example, genetic conditions may predispose them to certain issues, they may have some type of disability or disease that affects their physical development." (Personal communication, August 5, 2020, own translation).

Vulnerability is a way of naming children as “lacking,” since they are far from achieving autonomy over self-care. It is clear from the perspective of human development that the intrauterine developmental process is incomplete compared to that of other animals. Similar to other higher mammals, human infants require adult care for their survival. However, the context in which the vulnerability of children is discussed by teachers extends beyond the dependency on adults. It is associated, based on the researcher's analysis, with issues such as the violation of rights, socioeconomic disparities, social vulnerability, inclusion, and, generally, with a view of children as lacking autonomy and unable to fend for themselves. In this social context, where basic needs are not met, children are at a much greater risk. There is no evidence of an idealistic discourse promoting autonomous childhoods or self-actualization. Instead, the discourse reflects the reality of deprived children.

In this sense, vulnerability is less related to the characteristics of Early Childhood Development (ECD), typical of human beings, and more aligned with a vision of adultcentrism where the child is not recognized as an autonomous subject. That is, vital decisions are largely influenced by age and what is considered maturity of the individual, both cognitively and affectively.

This conception of childhood is ancient and has accompanied the thinking of cultures with Greco-Latin heritage. Since ancient times, children have been regarded as the future. This leads to a postponement of the child, who becomes significant only upon reaching adulthood. In this way of thinking about childhood, the future of the child's experience becomes the past of the adult (Mead, 2002); a conception that was strengthened in modernity and continues even in this historical and cultural moment, after the twentieth century, with the conception of rights ownership, because the cultural traces are deeply ingrained. The futurization of childhood as depicted in the teachers' narratives can be illustrated through one of the stories:

TTS 3RPPO10: [...] I contribute to it, to educate is to give the steps to the students so that they begin to visualize a future, so my future I see it being a doctor, a veterinarian, not only teach them to read and write but also that they themselves discover what they need and what they can assimilate for when they are young, so that they already visualize their future [...] so that they go as if starting to make a landing of what they want and can be in the future. (Personal communication, October 20, 2020, own translation).

These ideas of childhood, and what children are, are remnants of the Greco-Latin heritage that we maintain due to our history marked by the Spanish colony. Kohan (2004), as also noted by Durán (2015), in his conceptualization of childhood, draws from the Platonic writings of antiquity, retaining certain linguistic markers that continue to shape our understanding of children. One of these markers is characterized as "Childhood as the material of politics: the material of political dreams; discourse of necessity in perspective of a better future" (p. 46).

Teaching consists of preparing those who are not yet for when they will be. The subject is deferred in this conception, wherein the subjectum, the essential aspect of who one is, is not yet the possession of this being that is in formation. This also influences an idea of formation in which one is not yet a self as such but is the seed of who one will become. This conception of childhood, however, fails to acknowledge the child as an evolving subject with a developing sense of self. It denies the child's current subjectivity, relegating their personhood solely to adulthood.

One could highlight the underlying argument of this conception by taking it to its limits. For example, one could ask: When do you stop being in training and become a subject? When one becomes young or transitions to a school? Or, as the interviewed teacher suggests, at what point do children cease to think like children, devoid of a voice, and therefore become competent to choose, discern, and understand themselves?

The answer is simple, but not easy. Progressive laws maintain that individuals, regardless of age, always possess these capacities. Such is the case in Argentina, where Law 26,743 of 2012 allows individuals to change the registration of their gender identity at any time. There is no requirement for medical treatment, including for children, and in their daily lives, individuals are entitled to use their chosen first name.

This marks an international shift in perspective, where children are viewed not merely as recipients of guidance from adult caregivers who make decisions on their behalf, but as individuals entitled to their own rights. The law stipulates that parents may object, but it also considers what is deemed to be in the child's best interest and considers the child's input. Therefore, in the case of a boy or girl who wishes to change their gender, after completing the process of changing their name in the civil registry, there is an administrative requirement for schools and communities to address them by their chosen name (Stewart et al., 2020).

Consequently, when children are denied the opportunity to exercise their rights as equal subjects, their sense of agency and future prospects are undermined. This marginalization is evident in everyday school practices. Those who witness the daily schooling scene can discern whether the child is regarded as a subject of rights by observing the stance manifested in teachers' discourse and practices. From their conceptions, they respond to the child's voice, choices, personal belongings, or the exercise of free personality development. It is in their reflection on their practices where they reveal that they persist in envisioning the child's future without transcending the heteronomous role of the student.

Negligence, vulnerability, and deprivation are characteristic features of the modern conception of childhood, as the child is perceived as being heteronomous. This trait, evident in teachers' discourse as they reflect on childhood through their experiences, reflects an adult concern for ensuring that children are able to fully experience childhood during their formative years. A commendable concern, stemming from both the conception of modern childhood and the contemporary understanding thereof. Adults, especially those who are teachers, serve as guarantors and contributors to ensuring that childhood retains its essence. One of the representative accounts reflecting this position of teachers is as follows:

TTS 1CPO15: I think childhood is a time when children should be able to be happy and not be too worried or distressed. Unfortunately, there are children who already worry about economic, social, political, and other situations at a very young age. That's not right. Childhood should be a time to enjoy, play, and be very happy. (Personal communication, August 5, 2020, own translation).

Here begins a contrast to the vision of the child which emphasizes the child as a subject requiring protection. As historian Philippe Ariès (1987) observed, this perspective prioritizes constant "vigilance" over the child. This emanating from the modern conception. Children were encapsulated in schools so that they would not access the secrets of adult life, because Rousseau defined them as different beings. This conception of childhood as a time to be happy, and the desire for this condition to prevail throughout childhood, closely aligns with the vision of UNICEF, which is worth quoting:

Being a few years old is not equivalent to experiencing childhood. Adults envy children because childhood is perceived as a worry-free period, where the primary focus is on growing up and learning to navigate life. But childhood can be lost very early in life; when someone experiences significant challenges during childhood, we often say that "they have suddenly become an adult. (World State of Childhood cited by UNICEF and OEI, 2008, p. 15, own translation).

Here, the distinction is made between modern childhood, characterized by carefreeness, and childhood, which is a chronological and legal category. This is very important to demarcate the rights of children, and the issuance of laws in nation-states that guarantee these rights before the careless way in which adults become co-responsible for their upbringing. It is desirable that this condition be experienced in the first years of life, in childhood; however, this does not imply that childhood is exhausted simply by turning eighteen. Childhood does not inevitably belong to children; it belongs to human beings regardless of their age.

Arendt et al. (1993) have an interesting way of referring to this, as they argue that there is a problem with the line that divides children from adults. This line assumes that adults cannot learn new things or be treated as if they were the same as children. Likewise, they argue that it is not a rule dependent on age, as it depends on different factors in each socio-cultural context.

This shows how the separation between the adult world and the child world is being observed as a critical scenario challenging the fundamental assumptions of modern childhood, linked only to chronological age, and present whenever children can exercise their rights in accordance with adult-centric dispositions. This presents a critical problem of contemporaneity that transcends discussions about schooling and initial teacher training.

The ancient definition of childhood, meaning voiceless, has been perpetuated for centuries as a general rule to treat those excluded from the adult-centric, patriarchal world – or, if you prefer, heteropatriarchal – because that was the norm in Western culture. Throughout the twentieth century, attempts were made to give children a voice through active pedagogies, bills of rights, media exposure, etc. Hearing the voices of teachers who are beginning to conceive children with a voice is a transformative panorama for the context of teacher education. For example, one of the PFC teachers recounts her experience as follows:

TTS 3RPO24: Listening to them, returning the word. Yesterday, I watched a lecture by Carlos Skliar about conversations, specifically focusing on the strategy of conversation in the classroom. He highlighted the potential of conversations to facilitate learning among students. Instead of merely repeating information, engaging in conversations allows teachers to create an environment where children can learn together. [...] I think it is to identify what are those conditions that they have? As I mentioned just now, there are conditions for which we, as teachers, hold significant responsibility and have many possibilities. (Personal communication, February 28, 2020, own translation).

The contemporary conception begins to emerge among the professors of the PFC through the appropriation of state-of-the-art knowledge. In this case, reference is made to a renowned Latin American author, Carlos Skliar, who acknowledges childhood as a category that extends beyond chronological age. However, the argumentation doesn't solely rely on this; the interviewed teacher mentions it in relation to giving voice back to the child. In this sense, the conception of children as subjects of rights in the twentieth century has led to a profound transformation of the ancient concept of the voiceless child (infantia), which necessitated adults to speak on their behalf to ensure recognition of their rights. Now, there is a strong conviction that at the very least, children's voices should be heard and, more importantly, considered.

Some children, such as Greta Thumberg, Francisco Vera, Fernando de Lucio, Aleida Ruiz Sosa, and Malala, have gained exposure on digital media platforms and use their platforms to demand a change in the way contemporary childhoods are addressed. They advocate against being treated as minors due to the semantic baggage associated with that term.

The next step in pedagogical reflection on children's development, if we aim to address the adult-centric and adultocratic tendencies denounced by children, would involve critically examining the human model used for their education. This entails moving away from a condescending stance towards children and instead making efforts to truly listen to them, use respectful language, avoid stigmatization, provide comprehensive information, and integrate gender perspectives into discourse. This emerging stance, evident in the discourses of teachers involved in PFC training, represents a significant step forward—a window of opportunity for developing a more nuanced understanding of childhood and contemporary childhood.

The contemporary conception of childhood entails viewing this category as integral to the human condition, distinct from mere age and biology. It refers to childhood as a dimension that allows adults to experience rebirth, projections, dreams, and creativity; traits that were traditionally associated with childhood until recently. Contemporary childhood is shaped by multiple sciences and disciplines. In today's world, where birth rates are declining and life expectancy is increasing, adults are aging more slowly, resulting in a larger population of young people. Teachers perceive the cultural change and make it evident by recognizing themselves as infants being adults.

TTS 3REO25: "[...] or sometimes when you go out with friends, with family, you even become a child. You forget that you are already an adult who should not behave like a child. You start playing with small children and things like that, which can be done with certain family members. For example, with my mother, I am very spoiled, so I am both a mother and a girl with my father [...]" (Personal communication, August 5, 2020, own translation).

Contemporary childhood is situated within the realm of the human condition, conceived as a socio-historical construct rather than a purely biological phenomenon (Postman, 1983; Bárcena, 2002; Bárcena, 2009; Marias, 2005; Narodowski, 2016; Skliar, 2012). This modern cultural framework, which delineated a separation between children and adults, traces its origins to Rousseau's romantic theories (Ariès, 1987; Arendt et al., 1993; DeMause, 1991; Caril, 2011; Kohan, 2004). The division of society, fundamentally rooted in the establishment of certain topics as secrets (Elías, 1993; Postman, 1983; Manen, 2016; Mead, 2002), was structured in a way that access to these secrets was granted only after experiencing certain life moments or events. Knowledge about children began to have a place in words, customs, traditions, libraries, and eventually in school.

This division of the world has weakened over time, particularly with the advent of screens. Initially, it began with television screens and now extends to smartphones, computers, tablets, and other forms of communication that flatten the asymmetry between adults and children. The control over secrets no longer rests solely with adults such as parents, caregivers, or teachers. Instead, it resides in the contents of television, where the portrayal of children is often influenced by adult-centric perspectives.

What all this implies, I believe, is that our culture is offering fewer and fewer reasons and opportunities for children. TV creates a communication context that fosters the idea that childhood is neither desirable nor necessary, suggesting that children are not needed. When I mentioned the end of childhood, I did not mean the physical disappearance of children, although in some contexts, this is also occurring. Our birth rate has been decreasing for the past decade, resulting in the closure of schools across the country. (Postman, 1983, p. 20, own translation).

Some Latin Americans, like Carlos Skliar, align with Postman in distinguishing childhood from infancy, as evidenced in this research and through similar arguments. Additionally, it aligns with the unsustainability of modern childhood within today's educational institutions.

When referring to childhood as part of the human condition, one also observes a similar phenomenon in adults who are increasingly resistant to old age; for example, Narodowski refers to this phenomenon as "a world without adults." Children are being treated as adults without the mediation of family or school, influenced by the knowledge presented to them by the media. On the contrary, adults are beginning to resemble children more and more. There are multiple indicators that these characteristics of modern childhood present themselves unashamedly in adulthood throughout one's life because childhood is part of the life journey. For example, theories of development have migrated from focusing solely on childhood to encompassing all stages of life, including adulthood and even death.

Childhood is a category linked to the human condition, of a socio-historical nature, unrelated to age and the strict relationship with childhood. It is desirable from every point of view to live intensely in this period before the age of eighteen, but such intensity is not limited to youth; it can be linked to new experiences at any time in life. Viewed as births, they are an awakening of the childlike condition, even though one may be chronologically an adult or physically aged. We have noticed that the division of adults and children has faded in this cultural shift that some call “prefigurative” (Mead, 2002), others, liquid modernity (Bauman, 2003) postmodernity (Latour, 2007). Finally, it is evident to many that the distinctions between childhood and other stages of life are now less clear and asymmetrical. Teachers-in-training and trainers in TTS notice this, but without access to these frameworks.

However, among all adults, children must be guaranteed childhood. An African proverb, as quoted by Marina and referenced by Mesonero (2008), states that 'To educate a child, you need the whole tribe,' a sentiment with which the school teachers concur. They observe that ensuring children's rights is the shared responsibility of all stakeholders. They emphasize the essential relationship between schools and families as human and socio-historical institutions. These institutions are established and maintained for primary and secondary socialization (Pozo et al., 2004) and, simultaneously, for safeguarding children's rights (Álvarez-Uria & Varela, 1991). In the relationship between school and family, not only are the educational rights of boys and girls enshrined, but all their rights. This obligation is mandated by existing legislation, such as the Code of Children and Adolescents (2006).

Three distinct generations of teachers, who play key roles in teacher training in Caldas, have contributed their anecdotes, knowledge, and experience to the development of this process. The synthesis concludes by summarizing both the teachers' statements and the researcher's inferences. As this is a phenomenological process and in the pursuit of consistency with Van Manen's perspective, it aims to emphasize profound intuitions (Manen, 2016, p. 406), which transcend mere opinion.

Conceptions are ideas constructed from life experiences, reflecting what happens to us (Skliar, 2003; Larrosa et al., 2018; Larrosa, 2003). However, experience alone is not sufficient; it must undergo the process of reflection to reach the level of significance sought by researchers. This implies that teachers who narrate their experiences must reflect on past events, analyze those situations, and construct a narrative using their thoughts and insights. From theories of the mind, it is evident that only the individual themselves possess privileged access to their mental states. Their ability to use language, acquired from the surrounding environment, allows them to express these states, which are then recorded in text and rigorously analyzed to attain understandings that inevitably reflect aspects of reality. These individuals have undergone teacher training experiences in various roles: as regular school students, as teachers within the program responsible for training new educators, and as mentors guiding others in pedagogical practices. Through these experiences, they have developed a cognitive framework that informs their approaches to understanding childhood.

Regarding the conceptions of childhood expressed in teachers' discourses, it is noteworthy that one of the most prevalent is the view of childhood as both a stage of life and a stage of development, often referred to as "early childhood" or the "kindergarten age". Notably influenced by Piaget's theory of cognitive development, it makes it a determinant in teachers' thinking.

This decisive perspective in the conception of childhood represents a snapshot of the phenomenon, wherein teachers' discourses are characterized by being rooted in somewhat superficial or unsubstantial formative experiences. In the academic context, despite the explicit or implicit reference to Piaget, the understanding of the theory appears to be superficial, lacking foundation, elementary, and apparent. Discourses that perceive childhood as merely a stage of development, adhering to purist, scholarly, and enlightened positions expected in tertiary education environments, become distant. It is a reproduction of words lacking depth, which obscures contemporary theories of childhood behind this discourse, barely perceptible in their conceptions. Some PFC teachers acknowledge the historical evolution of the concept of childhood, recognizing the limited attention given throughout human history to understanding children and the significance of studying childhood.

The identity of the Teacher Training School as an institution has been shaped since its inception by the connection between childhood and pedagogy. In the context of the Teacher Training School's survival, this connection with childhood and pedagogy provides them with the capacity to maintain a place in the world. The field of early childhood or basic education becomes their niche for work, development, research, and prestige (de Guzmán, 1986).

Another prevailing conception in Teacher Training Schools is the Rousseauian idea of the division between the adult world and that of children, a notion that has come under scrutiny in recent times by scholars such as Arendt (1993), Bárcena (2009), Narodowski (2016), and Postman (1983), among others. While it can be argued that this idea is revolutionary, it also sparks new controversies and is challenging to accept because it disrupts established norms of the twentieth century, along with discourses and practices related to the shaping of contemporary childhood and perceptions of childhood abstractions. So, to this day, this topic remains largely undiscussed in Teacher Training Schools, and contemporary ideas continue to be obscured from teachers.

In none of the Teacher Training Schools does the discussion about the contemporary cultural changes involving childhood, as outlined in the social sciences, humanities, and philosophy, appear (Mead, 2002), which implies an acknowledgment of the "disappearance of modern childhood." It is evident that when the researcher questions them, there is a sense of nostalgia for the children who are forced to mature early, becoming someone different from the children who were once taught by teachers trained in the traditional Teacher Training School tradition during the twentieth century (Valencia, 2006; Loaiza, 2009). This theory is no longer enough for them to understand the changing culture and children of the present.

It is evident that the sense of longing for missing childhood is anchored in one's own experience. This is a natural phenomenon in human beings, as the conception of childhood has been developed and understood through experiencing childhood itself, through daily interactions with children at school, which serves as a social mechanism to separate them from the adult world. This presupposes as natural the existence of children, even to the extent of reducing them to the category of students, as it's impossible to separate the status of being a child from schooling.

It's evident that understanding early childhood as a developmental stage is not insignificant, as it contributes to comprehending children in pedagogical practice. It's essential to enhance our comprehension of childhood by distinguishing it from other related categories such as early child development, early childhood, and childhood studies. In all cultures, the delineation of life stages is arbitrary and largely contingent on cultural perceptions. Therefore, it's relevant to acknowledge alternative categories beyond age and biology to grasp contemporary childhoods and address the challenges of education in the future. The societal shift in attitudes towards childhood has spurred the emergence of a distinct field of study known as Childhood Studies. This interdisciplinary domain brings together various sciences and academic disciplines, influenced by diverse theoretical perspectives, but primarily shaped by political considerations. Its proximity to the quest for economic development underscores its significance in understanding and addressing contemporary issues surrounding childhood.

In teachers' discourses, the prevailing conception of modern childhood is characterized by traits such as vulnerability, imagination, carefree exploration, the assertion of rights, and a forward-looking perspective. Modern childhood is built from the 17th century to the end of the 20th century. Being a child throughout the twentieth century entailed adults' protection, the gradual unveiling of the mysteries of adulthood, and safeguarding their vulnerability against the perils of the world and the solitude of self. All of this unfolded within a pedagogical landscape grounded in moral discourses that refined the perception of the child within the realm of school education, culminating in the reduction of the child's identity to that of a mere student. In this sense, Narodowski's (1999) thesis on the reduction of the child to a student is masterful:

Being a student in the modern school institution essentially entails occupying a heteronomous position of not-knowing, in contrast to the figure of the teacher, an autonomous adult who possesses knowledge. Therefore, schooling essentially involves the process of infantilization of a segment of the population, who will then be reintegrated into school but as "students". Everyone who assumes the role of a student must relinquish their autonomy regarding their knowledge and position themselves in a dependent and heteronomous manner in front of a teacher who will determine what is taught. The school erased the prior knowledge of the students unless it fully coincided with what it aimed to transmit. Being a student in the modern school institution involved occupying a space for the inscription of knowledge and powers; a vulnerable body that must be shaped, disciplined, and educated according to pre-established socio-political utopias and methodological guidelines (p. 42, own translation).

The modern student became the object of schoolwork, a process of objectification that generates the universal idea of a child prefigured biologically and pedagogically. Students will be presented with the objects of the world chosen by adults to remove it from its crude initial condition, and you will seek humanity within it or place it upon it, preparing it for a life that seemingly begins when one ceases to be a child.

The contemporary conception of childhood moves beyond the notion of age as the sole determinant, it is therefore a concept that is not biological, having nothing to do with strength or deterioration; it is the narrative. Human life has an argument, it has a projective structure (Marías, 2005, own translation). It is important that, within the Teacher Training Schools (TTS), in alignment with their identity and purpose, there is a deeper exploration of the characteristics of contemporary childhoods. This exploration should move away from the foundational assumption of modernity regarding the absolute importance of age.

Authors like Julián Marías not only suggest the arbitrariness of life stages but also acknowledge the evolving nature of these stages in contemporary times. Old age and decline have been postponed, and there are continual new projects and births, even in advanced age (Arendt et al., 1993; Bárcena, 2009). The ages of life are not merely chronological or legal constructs; rather, they are deeply intertwined with our experiences and what unfolds in our lives, shaping who we are (Larrosa, 2003). In this regard, experiences such as births, learning processes, vulnerability, or maturity are not exclusive to a particular human group defined solely by the number of years they have lived. Childhood, therefore, permeates all stages of life, not solely defined by the predominant sentiments dictated by adults toward children (Ariès, 1987). In a world where even adults are seen as eternal, vulnerable youths (Narodowski, 2016), the result is that both these cognitive perceptions of human beings and their education are being left behind.

A characteristic of the conception of contemporary childhoods is the disappearance of children or what was once perceived as modern childhood, which could be seen as a postmodern artifice signaling the demise of numerous categories toward the end of the 20th century (Latour, 2007; García, 2007). This represents a necessary deconstruction of modern childhood as we know it, prompted by the cultural traits exhibited by children that differ from those that shaped the cognition and culture of modernity. It could be argued that childhood as a category is under construction, as a cultural and cognitive transformation emerging today is evident from various fields and modes of naming, pluralizing the once singular modern conception. Hence, contemporary childhoods are being discussed theoretically today.

This "contemporary" conception, which pluralizes childhoods, is categorized by researchers such as Narodowski and Baquero (1994) [Narodowski, 1999; 2016], while others refer to childhoods, such as Alvarado and Lobet (2013). In its plural form, it implies more than a demise; it signifies a transformative link with the socio-cultural and socio-historical realms of cultural change that modern childhood has encountered. The emergence of childhood in modernity reshaped society (Ariès, 1987), consequently influencing the design of schools (Comenius, 1657) and their subsequent implementation (Álvarez-Uria and Varela, 1991). It also gave rise to moral discourses that led to the development of pedagogy (Runge, 2017; Rousseau, 2000), and the establishment of teacher training institutions (Valencia, 2006; Báez, 2005; de Guzmán, 1986). The interconnection between childhood, schooling, pedagogy, and teacher training imbues significance and identity to the Teacher Training School as an institution. However, this historical narrative, which is both present and future-oriented, has not been embraced with a sense of identity. Consequently, there is a risk that Teacher Training Schools may face extinction in the near future, as witnessed in many countries (de Guzmán, 1986).

The emerging thoughts that teachers articulate in their speeches were challenging for them to name, describe, and comprehend. The cognition shaped through experience, referred to here as "conceptions," dictates the ways of acting, feeling, thinking, and portraying childhoods within the specific context of pedagogical practice. The potency of conceptions resides in their capacity to either enable or constrain the assimilation of new information, to imbue meaning into practical actions, and ultimately to shape the professional behaviors and practices of teachers. When conceptions are rooted in reductions of what can now be understood as contemporary childhoods, teacher training processes follow suit, owing to the synergistic relationship between conceptions and practices.

Various ways of conceptualizing childhood emerge in the teachers' discourses, exhibiting clear syncretism with different stages of life and the notion of developmental stages. An evident reference to Piagetian psycho-pedagogical theory, which has permeated the academic landscape of teacher training across the educational system. At the core of these studies lies biology, shaping a perspective rooted in the natural sciences that constrains childhood to a genetic preordained transition between different stages of life for all human beings.

Childhood, as a category, is a construct of human society, defined by the attribution of certain characteristics and a designated position within societal thought (Ortiz, 2006). As a category, childhood is subject to conceptualization, description, investigation, and analysis, which aim to break it down for better understanding. This is particularly emphasized in teacher training environments through the lens of social sciences, including sociology, anthropology, history, and even elements of philosophy.

Human beings construct conceptions based on their experiences of the world, which are symbolic (Alvarado and Lobet, 2013). Arendt (1993) critically argues that Rousseau's conceptualization of childhood, which divided the world into adults and children, was an error due to the resulting division it created. Similarly, while Rousseau is acknowledged as the father of modern pedagogy, it is widely recognized by contemporary authors that Philippe Ariès brought childhood to prominence as a category for scholarly inquiry in the twentieth century. This has made childhood a subject of research within the fields of social sciences and humanities.

Ariès's insight is that childhood, as a category, emerged in modernity due to new attitudes and sentiments towards children that were previously nonexistent. Several authors, including Lebrun (1975), Elías (1993), Njenga (1987), Ariès (1987), Vincent et al (1992), Narodowski and Baquero (1994), Trisciuzzi and Cambi (1993), and Narodowski (1999), converge on the recognition of Ariès as the historian or sociologist of childhood. Other scholars who align with this perspective include Mead (2002), Alzate (2003), Bárcena (2009, 2006), Enesco (2009), Runge (2017), Martínez (2013), and Narodowski (2016), all of whom attribute the conceptualization of childhood to the pioneering work of Ariès. It is noteworthy that upon conducting an epistemological analysis of these authors and their theoretical frameworks, they are situated within the disciplines of sociology, anthropology, philosophy, and history.

Childhood is not a biological category (Postman, 1983); it is one of thought, constructed by human beings. It is important to distinguish the concept of childhood from developmental stages, which are, in fact, social constructs. Different societies divide developmental stages in various ways, and this division is arbitrary, adopted for the sake of social discourse. This phenomenon is referred to as 'social construction,' which entails an understanding of reality shaped by the subjective perceptions or assumptions shared by members of a particular society at a given time (Papalia et al., 2009).

The above is intended to demonstrate that those who write about childhood, for the most part, do so from a historical, sociological, anthropological, or pedagogical perspective. In this sense, philosophers, educators, or researchers in education seek to understand the relationship between childhood and schooling. In response to the crisis in education and the erosion of childhood within the context of modernity, there is a growing focus on reimagining educational and training methodologies.

The teachers of the TTS of Caldas are closer to the conception of a childhood staged from biology and psychology. With the prevailing conception of childhood and a significant gap identified in the alignment between this conception and pedagogical practices, there is an evident and pressing need for teacher training to be updated. Despite the challenges, there is cause for optimism as some teachers in the PFCs have begun to explore childhood readings as a socio-historical category, thus recognizing the connections between childhood and pedagogy.

Teachers express confusion when attempting to determine whether childhood, like childhood, concludes at eighteen, as they acknowledge childlike traits within themselves as adults. They recognize that childhood transcends age and encompasses abilities such as playfulness, imagination, creativity, and vulnerability, as well as the capacity to initiate personal processes and projects, learn, grow, and embrace carefree or messy endeavors. These are characteristics of human behavior that can occur at any time in life.

Contemporary childhoods are diverse, stemming from the historical evolution of the category. At least three forms of construction are recognized: those of the old regime, characterized by the voiceless child and the abuses perpetrated against them; that of modernity, emerging in Western society from the seventeenth century, which was psychopedagogically reduced to the category of student and culturally and legally evolved into recognizing children as subjects with rights in the twentieth century; and contemporary childhoods, which are hyper- or derealized (Narodowski, 1999; 2016).

Teachers in training in the Caldas schools make sense of modern childhood. It's crucial to emphasize that these constructions are representative across all three layers of teachers interviewed. This indicates that within the context, there has been a lack of sufficient theoretical exploration into the frameworks of contemporary childhoods. These frameworks now distinguish childhood from infancy and Early Childhood Development (ECD), placing childhood along the entire trajectory of life. They focus on comprehending the significance of intervening in early cognitive development to enhance the effectiveness of pedagogical practices in shaping individuals' lives.

The ways in which teachers conceptualize childhood, children, developmental stages, schooling, teacher training, and pedagogy are cognitive constructs that profoundly shape their interactions with children and the surrounding community. Embracing a cognitive framework rooted in contemporary theories of childhood can foster an understanding of its essential role within Teacher Training Schools. This understanding can then inform efforts to enhance pedagogy and research within the teacher training context, ultimately empowering educators who are entrusted with shaping childhood development.

Teachers are always in training and can modify their conceptions, their cognition and, therefore, their ways of conducting pedagogical practices. Throughout the identified categories, significant issues requiring attention have emerged, shaped by the cognitive frameworks of teacher groups. These issues often recur without thorough reflection. Specifically, mention is made of principles outlined by Ariès, such as courtesy and vigilance, alongside concepts like adultcentrism and adultcracy, which children actively highlight within societal dynamics. Moreover, the role of the family in fulfilling the teacher's communal responsibilities is emphasized. Teacher training scenarios could engage in discussions critiquing the prevailing model of human beings, aiming to instigate change within pedagogy.

Abelleira, Á. & Abelleira, I. (2019). De lo infantil, escuchando al corazón y tomando el pulso. Memorias I Congreso Internacional de Prácticas Pedagógicas (pp. 1-5). Universidad de Caldas.

Abric, J.-C. (2001). Prácticas sociales y representaciones . Ediciones Coyoacán S.A.

Alvarado, S. V., & Lobet, V. (2013). Introducción. In V. Llobet (Comp.), Pensar la Infancia desde América Latina (pp. 27-34). CLACSO.

Álvarez-Uria, F. & Varela, J. (1991). Arqueología de la Escuela . La Piqueta.

Alzate, M. V. (2003). El descubrimiento de la infancia, modelos de crianza y categoría sociopolítica moderna. Revista de Ciencias Humanas, 201( 31), 1-9. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/277030979_El_descubrimiento_de_la_infancia_II_modelos_de_crianza_y_categoria_sociopolitica_moderna

Arendt, H., Romero, J. & Cerdán, J. B. (1993). La crisis de la educación. Cuaderno Gris. Época II, 7 , 38-53. https://repositorio.uam.es/handle/10486/260

Ariès, P. (1987). El niño y la vida familiar en el antiguo régimen . (N. G. Guadilla, Translator). Taurus.

Báez, M. (2005). Las Escuelas Normales colombianas y la formación de maestros en el siglo XIX. EccoS Revista Científica, 7 (2), 427-450. https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=71570210

Bárcena, F. (2002). Hannah Arendt: Una poética de la natalidad. Daimon, (26), 107-123. https://revistas.um.es/daimon/article/view/11921

Bárcena, F. (2006). Acerca de una pedagogía de la existencia: la filosofía de la educación y el arte de vivir. Aloma: revista de psicologia, ciències de l'educació i de l'esport Blanquerna , (19), 245-262. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=2201340

Bárcena, F. (2009). Una pedagogía del mundo. Aproximación a la filosofía de la educación de Hannah Arendt. Anthropos , (224), 113-139. https://www.academia.edu/1468080/Una_pedagog%C3%ADa_del_mundo_Aproximaci%C3%B3n_a_la_filosof%C3%ADa_de_la_educaci%C3%B3n_de_Hannah_Arendt_en_Revista_Anthropos_no_224_pp_113_139

Bauman, Z. (2003). Modernidad Líquida . (Rosenberg, M. Translator.) Fondo de Cultura Económica.

Caril, S. (2011). La memoria de la infancia. Estudios sobre historia, cultura y sociedad. Paidós

Código de la Infancia y la Adolescencia [CIA]. Law 1098 of 2006. November 8, 2006. (Colombia).

Comenius, J. A. (1657). Didáctica Magna . Porrúa.

de Guzmán, M. (1986). Vida y Muerte de las Escuelas Normales: Historia de la formación del magisterio básico . PPU Promoción Publicaciones Universitarias.

Decreto 1236 de 2020 [Ministerio de Educación Nacional]. Por el cual se adiciona el Capítulo 7 al Título 3 Parte 3 Libro 2 del Decreto 1075 de 2015 - Único Reglamentario del Sector Educación- y se reglamenta la organización y el funcionamiento de las Escuelas Normales Superiores como instituciones educativas formadoras de docentes . September 14, 2020.

DeMause, L. (1991). La evolución de la infancia. Historia de la infancia . Alianza.

Durán, M. (2015). El concepto de infancia de Walter Kohan en el marco de la invención de una escuela popular. Childhood & Philosophy, 11 (21), 163-186. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/5120/512051494011.pdf

Elías, N. (1993). El proceso de civilización. Fondo de Cultura Económica.

Enesco, I. (2009). Concepto de Infancia a lo largo de la historia . Universidad Complutense de Madrid.

García, O. J. (2006). Las tendencias educativas en las tesis de los maestros normalistas y su incidencia en la formación superior del magisterio colombiano en el período de 1936 a 1948 (Specialization thesis). Universidad de Caldas, Manizales, Colombia.

García, P. (2007). Bruno Latour y los límites de la descripción en el estudio de la ciencia . Editorial de la Universidad de Granada.

García, O. (2023). Concepciones de infancia y pedagogía de los maestros de las Escuelas Normales Superiores de Caldas (Doctoral thesis). Universidad de Caldas, Manizales, Colombia. https://repositorio.ucaldas.edu.co/handle/ucaldas/19707

García, O. J. (2019). Infancia, pedagogía y formación de maestros en los programas de licenciatura de la Universidad de Caldas . Universidad de Caldas. Unpublished

García, O. J. & Osorio, M. E. (2020). Concepciones de infancia que subyacen a las prácticas pedagógicas de maestras de educación inicial. Revista Latinoamericana de Estudios Educativos, 16 (1), 211-232. https://revistasojs.ucaldas.edu.co/index.php/latinoamericana/article/view/2295

García, O. J. & Valencia, C. H. (2002). La formación del maestro normalista de Manizales en el área de Educación Física durante la década del cuarenta del siglo XX. Revista de Educación Física y Recreación , (13), 71-84. https://biblat.unam.mx/es/revista/revista-educacion-fisica-y-recreacion

Greimas, A. (1979). Semántica Estructural: investigación metodológica . Gredos.

Guzmán, R. J. & Guevara, M. (2010). Concepciones de infancia, alfabetización inicial y aprendizaje de los educadores y educadoras. Revista Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales, Niñez y Juventud , 8 (2), 861-872. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/773/77315155007.pdf

Hernández, R., Fernández, C. & Baptista, P. (2006). Metodología de la Investigación . Mc Graw Hill.

Jiménez, A. (2011). La tardía instalación de la teoría del desarrollo cognitivo de Jean Piaget en Colombia 1968-2006. Revista colombiana de educación , (60), 123-140. https://revistas.pedagogica.edu.co/index.php/RCE/article/view/845

Jiménez, A. (2017). Pensamiento pedagógico colombiano: Martín Restrepo Mejía. Una mirada a sus conceptos de pedagogía, infancia, maestro y escuela. Revista Historia de la Educación Latinoamericana, 19 (29), 245-269. https://www.redalyc.org/journal/869/86954033011/html/

Kohan, W. O. (2004). Infancia entre educación y filosofía . Laertes.

Larrosa, J., Christine, K. & Jaques, C. (2018). Elogio del profesor . Miño Dávila.

Larrosa, J. (2003). La experiencia de la lectura . Fondo de Cultura Económica.

Latour, B. (2007). Nunca fuimos modernos . Siglo XXI Editores.

Lebrun, F. (1975). Philippe Aries, siglos de Niñez . El Umbral «Puntos-historia».

Loaiza, Y. E. (2009). Sabio o Erudito: el maestro de las Escuelas Normales de Caldas 1963-1978 . Universidad de Caldas.

Law 26.743 of 2012. Establécese el derecho a la identidad de género de las personas . May 23, 2012 (Argentina).

Manen, M. V. (2016). Fenomenología de la práctica: Métodos de donación de sentido en la investigación y la escritura fenomenológica . Universidad del Cauca.

Marías, J. (2005). Las edades de la vida. Conferencia de Julián Marias . https://solidaridad.net/las-edades-de-la-vida-conferencia-de-julian-marias3087/

Martínez, M. V. (2013). La cultura material y la educación infantil en España. El método Froebel (1850-1939) (tesis doctoral) . Universidad de Murcia, España. https://digitum.um.es/digitum/handle/10201/30144

Mead, M. (2002). Cultura y compromiso: el mensaje de la nueva generación . Editorial Gedisa.

Mesonero, A. (2008). Aprender a vivir, conviviendo bien: competencia social y cívica. International Journal of Developmental and Educational Psychology, 2 (1), 427-438. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/3498/349832317045.pdf

Narodowski, M. (1999). Después de clase. Desencantos y desafíos de la escuela actual . edu/causa.

Narodowski, M. (2016). Un mundo sin adultos . Debate.

Narodowski, R. y Baquero, R. (1994). ¿Existe la infancia? Revista del Instituto de Investigaciones en Ciencias de la Educación IICE , (4), 1-10.

Njenga, G. (1987). A Social History of Family Life . https://su-plus.strathmore.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/86081d16-f2c7-48d4-b112-7b91adf55abb/content

Ortiz, A. (2006). Cassier y las formas simbólicas. In Ortiz, A. and Lanceros P., Diccionario de Hermenéutica (pp. 41-48). Universidad de Deusto.

Papalia, D., Wendkos, S. and Duskin, R. (2009). Psicología del Desarrollo, de la infancia a la adolescencia. McGrawHill.

Postman, N. (1983). La desaparición de la niñez. Boletín Iberoamericano de Teatro para la Infancia y la Juventud , (31), 1-24. https://www.cervantesvirtual.com/obra/boletin-iberoamericano-de-teatro-para-la-infancia-y-la-juventud-32/

Pozo, M., Álvarez, J. L. & Luengo, J. (2004). Teorías e instituciones contemporáneas de educación . Biblioteca Nueva.

Ricoeur, P. (2002). Del texto a la acción: ensayos sobre hermenéutica . Fondo de Cultura Económica.

Rousseau, J. J. (2000). El Emilio o de la Educación . (R. Viñas, Trad.) elaleph.com.

Runge, A. K. (2017). La conformación disparatada de la pedagogía: entre disciplinarización y profesionalización. Conferencia Inaugural Doctorado en educación, Seminario de pedagogía, Universidad de Caldas (págs. 1-17). Universidad de Caldas, Manizales.

Skliar, C. (2003). La experiencia de la lectura: estudios sobre literatura y formación . Fondo de Cultura Económica.

Skliar, C. (2012). La infancia, la niñez, las interrupciones. Childhood & Philosophy, 8 (5), 67-81. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/5120/512051606004.pdf

Stewart, V., Narodowski, M. & Campatella, M. (2020). Infancias trans: otra disrupción en las escuelas de la modernidad. Revista Colombiana de Educación, 1 (82), 263-280. https://revistas.pedagogica.edu.co/index.php/RCE/article/view/10804

Trejo, F. (2012). Fenomenología como método de investigación. Revista De Enfermería Neurológica, 11 (2), 98–101. https://doi.org/10.51422/ren.v11i2.138

Trisciuzzi, L. & Cambi, F. (1993). La infancia en la sociedad moderna: del descubrimiento a la desaparición . Riuniti

UNICEF, OEI. (2008). Plan de formación: Innovaciones en educación y atención infantil en programas formales y no formales. En el marco del proyecto: Instituto para el Desarrollo y la Innovación Educativa (IDIE-OEI) en Educación Inicial y Derechos de la Niñez. Unicef.

Valencia, C. H. (2006). Las Escuelas Normales y la formación del magisterio: primera mitad del siglo XX . Rudecolombia.

Vincent, G., Simon-Nahum, P., Leveau, R., Schnapper, D., Ariès, P. & Duby, G. (1992). Historia de la vida privada. El siglo XX: diversidades culturales. (J. L. Cremades, Trad.). Taurus.

Zimmerman, M. A. (2004). Las teorías académicas y las concepciones personales en la formación docente. XI. Jornadas de investigación. Facultad de Psicología. Universidad de Buenos Aires.

Zimmerman, M. A. & Trabazo, M. F. (2015). ¿Qué piensan los docentes acerca de lo que enseñan? Concepciones personales sobre los contenidos escolares. Revista Educación Cultura y Sociedad, 5 (2), 121-135.

1 Research carried out by the author as a doctoral thesis entitled « Concepciones de infancia y pedagogía de los maestros de las Escuelas Normales Superiores de Caldas ». Affiliated with the Research Group Teachers and Contexts at the Universidad de Caldas. Financing: Own financing. Declaration of interests: The author declares that there is no conflict of interest. Data availability: The research data are in the repository of the Universidad de Caldas: https://repositorio.ucaldas.edu.co/handle/ucaldas/19707

2 PhD and Master’s Degree in Education. Specialist in University Teaching, Universidad de Caldas. Email: omar.garcia@ucaldas.edu.co