How to quoteRodríguez-Ávila, Y et al ., (2024). Social Representations of the Corralejas Tragedy of January 20, 1980, Sincelejo, Colombia. Ánfora, 31 (57), 95 - 119 . https://doi.org/10.30854/anf.v31.n57.2024.1107 |

Yildret Rodríguez-Ávila2 https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2077-5121 CvLAC https://scienti.minciencias.gov.co/cvlac/visualizador/generarCurriculoCv.do?cod_rh=0000117294 Venezuela Jorge Luis Barboza3 https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6743-428X CvLAC https://scienti.minciencias.gov.co/cvlac/visualizador/generarCurriculoCv.do?cod_rh=0000078229 Venezuela Nubia Ester Hernández Flórez4 https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8756-1895 CvLAC https://scienti.minciencias.gov.co/cvlac/visualizador/generarCurriculoCv.do?cod_rh=0001360807 Colombia Olena Klimenko Klimenko5 https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8411-1263 https://scienti.minciencias.gov.co/cvlac/visualizador/generarCurriculoCv.do?cod_rh=0000757896 Colombia |

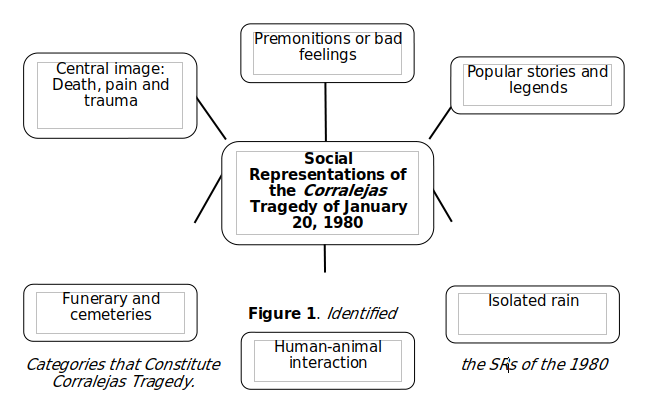

Objective: To reveal the Social Representations (SRs) that the population of Sincelejo, department of Sucre, Colombia, has regarding the Corralejas tragedy of 1980, which occurred in that city. Methodology: Grounded theory, applied to the analysis of information that was collected from various sources, key informants, and texts found on social networks through videos and comments. Finally, the information was analyzed using Atlas.Ti. Results: Six categories were revealed: premonitions or bad feelings, popular stories and legends, isolated rain, human-animal interaction, funerary aspects and cemeteries, and, finally, the central image associated with death, pain and trauma. Conclusions: The categories revealed become SRs of tragedy from the concretization of magical thinking, which sought non-rational and less stigmatizing explanations of a tradition that clashes with the modernity, and that has deep cultural roots in the Colombian Caribbean region.

Keywords: social representations; magical thinking; bullfighting festivals; corralejas ; customs and traditions; Colombia; Sincelejo (obtained from the UNESCO thesaurus).

Objetivo: develar las representaciones sociales (RRSS) que la población de Sincelejo, departamento de Sucre, Colombia, tiene sobre la tragedia de las Corralejas de 1980, ocurrida en esa ciudad. Metodología: teoría fundamentada, aplicada al análisis de la información que se recopiló de diversas fuentes; informantes clave y textos encontrados en redes sociales a través de vídeos y comentarios. Finalmente, la información se analizó utilizando Atlas.Ti. Resultados: se revelaron seis categorías: premoniciones o presentimientos, historias y leyendas populares, lluvia selectiva, interacción humano-animal, aspectos funerarios y cementerios; y, finalmente, la imagen central asociada a la muerte, dolor y trauma. Conclusiones: las categorías develadas se convierten en RRSS de la tragedia a partir de la concreción del pensamiento mágico, que buscó explicaciones no racionales y menos estigmatizadoras de una tradición que choca con la Modernidad, y que tiene profundas raigambres culturales en la región Caribe colombiana.

Palabras clave: representaciones sociales; pensamiento mágico; fiestas taurinas; corralejas; costumbres y tradiciones; Colombia; Sincelejo (obtenidos del tesauro de la UNESCO).

Objetivo: revelar as representações sociais (RRSS) que a população de Sincelejo, departamento de Sucre, Colômbia, tem sobre a tragédia das Corralejas de 1980, ocorrida nessa cidade. Metodologia: teoria fundamentada, aplicada à análise das informações coletadas de diversas fontes; informantes-chave e textos encontrados em redes sociais, através de vídeos e comentários. Por fim, as informações foram analisadas utilizando o software Atlas.ti. Resultados: se revelaram seis categorias: premonições ou pressentimentos, histórias e lendas populares, chuva seletiva, interação humano-animal, aspectos funerários e cemitérios; e, finalmente, a imagem central associada à morte, dor e trauma. Conclusões: as categorias reveladas se tornam representações sociais da tragédia a partir da concretização do pensamento mágico, que buscava explicações não racionais e menos estigmatizadoras de uma tradição que confronta a Modernidade e que possui profundas raízes culturais na região do Caribe colombiano.

Palavras-chave: representações sociais; pensamento mágico; festas taurinas; corralejas; costumes e tradições; Colômbia; Sincelejo (obtidas do tesauro da UNESCO).

Spanish colonization left a legacy of traditions with the American peoples, and one of them is bullfighting. This was adapted and syncretized in the Latin American context, and gave rise to various bullfighting activities such as coleo, corralejas and toropukllay. This article focuses on the “Fiesta en Corraleja”, an activity that evolved from the rural resident’s work on livestock farms to becoming a popular celebration. Although when it stopped being a private practice and became a public event is not known precisely, the practice dates back to 1827, according to the Sucreño journalist José Cisnero Arriaga (Flórez, 2008, p. 153).

The “Fiesta en Corralejas” is a popular tradition of the Colombian Caribbean region, which consists of a bullfighting show in which the local population interacts with cattle and horses, animals that arrived in the area because of colonization. This celebration originated mainly in the current departments of Sucre and Córdoba, located in the north of Colombia in an area of coastal savannas where livestock ranches started developing (Hernández, 2014, p. 145). To date, corralejas are carried out in 102 municipalities in the departments of Atlántico, Bolívar, Cesar, Córdoba, Magdalena, and Sucre (Niampira & Barguil, 2021).

Such is the importance that it gained over the years, that the current size of the bullring exceeds up to four times that of any in Colombia (Arrieta & Díaz, 2010, p. 41). For the locals, the festivity is divided between what happens in the arena, and what is taking place in the boxes: Family gatherings, meetings, exchange of drinks, betting and more. All this constantly accompanied by band music and fandango (Turbay, 1995, p. 28). The Corralejas were declared Cultural Heritage of the Nation (Law 1272, 2009), despite strong criticism (Hernández, 2013)(Hernández, 2013).

Initially, the corralejas were held in the Plaza de San Francisco, and this was the case for 85 years (Flórez, 2008, p. 154). However, the date and place changed. Sebastián “Chano” Romero, a prominent member of the traditional society of Sincelejo, proposed changing them to January 20 to commemorate his saint (Fals, 2002b, p. 97). Likewise, the transfer was made to Plaza Majagual because the space in the center was already insufficient. The purpose also changed: from honoring Saint Francis of Assisi, to honoring the “Sweet Name of Jesus,” which in the Christian liturgy is the 3rd of January.

However, on January 20, 1980, a tragedy occurred that marked a before and after in the history of Las Corralejas. That day, a wing of the boxes collapsed, causing the death of between 200 and 400 people, although the exact number remains uncertain due to the circumstances and lack of organization at the time. This unfortunate event generated a series of stories that have become social representations (SRs) of the tragedy.

The dispute remains in collective memory over who would provide the bulls for that January 20 as part of the beginning of the tragedy. Arturo Cumplido, a rancher from the region, used to offer his bulls as a religious promise to the Sweet Name of Jesus (Movilla, 2003). However, the political spokesmen of Pedro Juan Tudela, another rancher, won the dispute and took away the participation of the bulls for the central day of the festival. This act was recorded in the memory of the people and is constantly mentioned when remembering what happened in the Corralejas of 1980.

Furthermore, the tragedy was the result of a series of circumstances that revealed the lack of foresight in the face of a large-scale event. Among these, it can be mentioned that the prior evaluation of the land where the boxes were built was deficient, as was the technicalities of the artifact. Likewise, more tickets were sold than capacity allowed. There was also torrential rain that forced spectators to seek shelter in the covered areas, causing an imbalance in the boxes. There was a landslide which exposed the wooden posts and caused the collapse. People on the upper floors fell onto those below, resulting in the numerous deaths and injuries.

The capacity of morgues and hospitals was insufficient to care for the wounded and handle the corpses. Many bodies could not be identified, so a mass grave had to be used. To date, the exact death toll remains imprecise. Given the importance of this celebration and the symbolic, historical, and cultural significance of the event, an investigation has been carried out to analyze the social representations of the citizens of Sincelejo, regarding the tragedy of January 20, 1980.

Due to the relevance of the event and its unusualness, apart from its tragic element, January 20, 1980 is remembered by the inhabitants of Sincelejo; both by those who experienced the event firsthand and those who learned about it from the stories of its actors. In this sense, revealing the SRs that the inhabitants of Sincelejo have regarding the tragedy of "Las Corralejas de 1980" is proposed.

Keeping in mind that the epistemological foundation is based on Moscovici (1979) is important. He clarifies that SRs are almost tangible. This is because most of the SRs that an individual establishes are loaded with representations, due to the symbolic implications they entail and the practice they develop repeatedly as a ritual. Thus, by giving SRs meaning, the individual internalizes them and makes them his/her own (Moscovici, 1979, p. 38).

Consequently, SRs require experience and its cognitive appropriation that gives them meaning. If this experience is also ritualized, it becomes a belief system that is difficult to detach from and analyze. SRs can be said to be complex conglomerates that cover cognitive, emotional, social and, sometimes, physical aspects, which are integrated into a single notion or concept associated with events, situations, entities or even objects, either individually or combined. These phenomena, which Jodelet (1986, p. 475) defines as “objects,” can have roots in the mythical or the imaginary realms. In the specific context that concerns this article, the question arises: How have the SRs around the Corralejas tragedy of January 20, 1980 been configured and kept alive?

Clarifying that the link between theories of collective memory and SRs is significant in at least three aspects is also important. First, collective memory and social representation share similarities, since both are symbolic constructions rooted in diverse social and cultural groups. Second, collective memory maintains the continuity of social categories of action when creating a social representation of an object. Third, Moscovici (1979) suggests that SRs are analyzed through the definition of a subject and an object of representation. Who represents what? In the study of collective memory, the same initial approach can be adopted. Who remembers what? (de Alba, 2012).

In this qualitative study, grounded theory was used as a methodology to “obtain complex details of some phenomena, such as feelings, thought processes and emotions, difficult to extract or apprehend by more conventional research methods” (Strauss & Corbin, 2002, p. 21). In essence, this method has three components: First, data are obtained through various means: interviews, participant observation, documents, records, and films; second, the data is organized and interpreted through the procedures chosen by the researchers that involve coding them and establishing relationships amongst them; finally, the report is written and submitted to the scientific community.

In this sense, information was collected from various sources, including key informants who met the following criteria: people who had experienced the tragedy firsthand and people who, although had not been there, remembered the event because they had heard about it from their childhood. In addition, there was a body of texts collected on social networks such as Facebook, YouTube (videos and comments on those videos), news, testimonies on the web and books published about the January 20th Corralejas tragedy that tangentially addressed the topic.

Techniques such as in-depth interview and focus group were used to collect information (coded as SP and placed in italics). In this case, double interviews were carried out with the same informants until saturation was reached. The analysis of the corpus was carried out based on coding, and the Atlas.Ti software was used.

Of note: Grounded Theory is not opposed to the theory of social networks, but rather, both can be intertwined and complement each other. In this sense, Jodelet (1986) argues that SRs, as phenomena, manifest themselves in various ways that shows their versatility and multiplicity in the social and cultural sphere.

Images that condense a set of meanings, reference systems that allow us to interpret what happens to us, and even give meaning to the unexpected, categories that serve to classify circumstances, phenomena, and individuals with whom we have something to do, and theories that allow facts to be established about them. And often, when understood within the concrete reality of our social life, SRs are all of these together. (p. 472, own translation).

In this way, Grounded Theory, with its distinctive inductive approach, enables an in-depth exploration of social networks, facilitating the identification of patterns, categories and emerging meanings associated with them. This methodology also allows understanding underlying meanings, such as images that synthesize various meanings and categories that classify circumstances, phenomena, and individuals.

Within the framework of this research, the data obtained through the various techniques and resources previously mentioned, were explored with the aim of identifying a set of categories. These are intended to reveal the collective imagination associated with the object of study, and allow a deeper and more structured understanding of the shared perceptions and conceptions around this topic.

From the information collected and analyzed, six categories have been identified (Figure 1) that are considered part of the SRs of the inhabitants of Sincelejo regarding the tragedy. These categories serve to label collective memory and to appropriate a devastating event. The analysis of the research related to each of the categories is presented.

Below, evidence is presented that offers a detailed vision of the events and circumstances that surrounded the Corralejas tragedy, and that generated popular beliefs around it.

|

Movilla (2003) states that there were three warnings that indicated that a tragedy was going to occur at the Corralejas festivals: 1) “The torrential downpour of that day, January 20, 1980, left a feeling that something was going to happen at the festival of The Sweet Name of Jesus” (p. 27, own translation); 2) "politics took over all the coastal Corralejas" (p. 35, own translation); and, 3) the fact that they had "taken away" the bulls from Arturo Cumplido (p. 42, own translation). |

|

Rural residents without political malice thought that the disruption of tradition was a bad omen. And on the 20th, they went to the bullfight with the feeling, hidden behind their brows, that something disastrous was going to happen at the Corraleja. (Movilla, 2003, p. 126). |

|

“Some events preceded the festivities of 1980 that have given rise to conjectures on the part of the people of Sincelejo. Arturo Cumplido promised, since 1962, to the “Sweet Name of Jesus” to bring the bulls every January 20 until the day of his death. That year the board denied him the day and it was awarded to Pedro Juan Tulena, which is why the people of Sincelejo feared a tragedy that day.” (El Cenit, February 11, 1980. Para. 2, own translation). |

|

A victim of the tragedy narrates: "I remember that at that time [...] it could have been six in the morning, yes, a neighbor passing by was telling all of us who were outside not to go to Corraleja because that day the boxes were going to fall." (It's always rains in January 2021, 0m25s, own translation). |

|

My little brother and I had a chicken, and it was black, and she [aunt] was dressing me up. The little chicken starts to go around and around me and my little brother. They were dressing me up before going to the Corralejas, the one who dressed me up was Nurys. Then she picked up the chicken and threw it in the hallway “go bother over there.” About an hour after my sister threw the chicken it died. They say that he picked up the dead man who was my father, that is, a tragedy was going to happen in the house and my father did not die. (SP22, personal communication, September 22, 2022, own translation). |

The cited texts reveal various indications and conjectures about the tragedy in Las Corralejas. First, what Movilla stated about the three warnings that anticipated the disaster; the supernatural events, such as the one narrated by the informant SP22, and the story commented on social networks about the omen of a stranger. Thus, a series of events emerged that generated a premonition in the community of Sincelejo, and that arose from considering the disruption of tradition as a dire omen.

Below is the information collected from the informants that sheds light on the events that preceded the tragedy at the Corralejas festivals.

|

As usual, January 20 was a special date for Arturo Cumplido, they denied him that day, January 20, they gave it to another rancher, and that day it rained only in the Corraleja that the boxes fell and there were many deaths. Then they said he had a pact with the devil and they gave that date again to Arturo Cumplido. Supposedly he had a pact with the devil, that's what they said. (SP16, personal communication, August 2, 2022, own translation). |

|

My father, who at that time was a band musician, tells me that it was horrible, that the dead fell into the pots where they fried food and so on, and he also tells me that that day it only rained in that area where the Corralejas were and also says that that day they were not going to throw out Arturo's bulls since that guy had a pact with the devil. I still don't understand how they celebrate that day with pride, knowing that so many people died. (SP10 personal communication, July 15, 2022, own translation). |

|

I studied with one of Arturo Cumplido's sons. According to the legend that they told me, the accident had already occurred some time ago when I asked them: Hey, is it true? What they say your dad? That the Corralejas fell because they didn't give him the bull day? And he tells me: “Man, Beatri, according to legend and according to what I was able to hear from my father, they said that he had a pact with the Devil, because every January 20, the Corralejas were his. That time they did not give the Corralejas to Arturo Cumplido, but rather they gave them to him on the 22nd, and he said either they give them to him on the 20th or he won't launch a bull.” (SP22 personal communication, September 22, 2022). |

|

The shot, in the initial moments, is a pan over the sky that is getting dark, as if to mean that something is going to happen. The panning is in the Mochila bullfighting ring. The gray tone gradually turns dark gray until it’s black. Some lightning, captured on camera, resembles the horns of a gigantic bull. The horns can be seen on the screen at least three times. (Video referred to by Movilla, 2003, p. 130, own translation). |

|

Peasants without political malice thought that the disruption of tradition was a bad omen. And on the 20th, they went to the bullfight with the feeling, hidden behind their brows, that something disastrous was going to happen in the Corraleja. (Movilla, 2003, p. 126, own translation). |

The evidence collected reveals a series of beliefs and rumors that surrounded the Corralejas tragedy and that were shaped into popular legends of the region. According to testimonies, Arturo Cumplido, a local rancher, was denied the privilege of providing the bulls on January 20. There is speculation among the population of Sincelejo that Cumplido had a pact with the devil, and that his denial of the day of the bulls led to the tragedy. This idea is reinforced with the story of the video captured during the event that showed suggestive images, like lightning that resembled bull horns.

The information obtained from the informants reveals an interesting and complex related phenomenon: the occurrence of isolated rain.

|

January 20, traditional day, packed to bursting, there was no chance of the sky becoming overcast with rain at all, splendid sun, monumental sun. I think that around 3:30 in the afternoon the sky began to cloud, and it became cloudy and cloudy, but it was a cloud over the sector [...] that of the bullfighting ring. And it begins to apply pressure and it rains in torrents, without stopping, it rains and rains and it unleashes a superb, tremendous downpour, not a regular storm, a real downpour, really. (Gómez, 2020, 2m34s) (own translation). |

|

The cloud is positioned […] it is fixed on the Corraleja. (Gómez, 2020, 3m5s) (own translation). |

|

[…] and that day it rained only and so much in the Corraleja, that the boxes fell. (SP16, personal communication, August 2, 2022, own translation). |

|

When I arrived here at the house, it was not raining, it had not rained here, that is true, it did not rain here. (SP20, personal communication, September 22, 2022, own translation). |

|

Movilla (2003, pp. 129-131) publishes the story attributed to a former member of a security organization now abolished from Colombia, who claims that he found himself in an operation related to satanic sects in Sincelejo, a video of the day of the tragedy never made public: The shot, in the initial moments, is a pan over the sky that is getting dark, as if to mean that something is going to happen. The panning is over the Mochila bullfighting ring. The gray tone gradually turns dark gray until it’s black. Some lightning, captured on camera, resembles the horns of a gigantic bull. The horns can be seen on the screen at least three times. It seems that the cameraman knows what is going to happen because by panning he searches the sky for the signal. Much of the film focuses on the space above the Corraleja, because the ceilings of the boxes are left at the bottom of the screen, as a background that confirms the stage. The filming, according to the angles, was done from one of the sides of the construction that did not fall. You can see when the rain falls and perhaps with the boxes very close to falling, the filming is interrupted and then the view of the collapsed boxes continues, just as they appeared in the newspaper photos. |

This evidence adds an additional level of complexity, as testimonies indicate that rain played a crucial role in the event, but in an unusual and focused way. The stories highlight that the rain only affected the space where the Corraleja was located, while in other surrounding areas there was no rainfall. These observations suggest a localized rain, which raises questions about its origin and nature among the residents. The idea of supernatural rain is reinforced with the story of the former member of a security agency about the hidden video that shows a pan of the sky gradually darkening over the Corraleja, with lightning that resembles the horns of a gigantic bull.

The interaction between humans and animals has been the subject of study in various scientific disciplines and, in particular, the relationship between humans and bulls in cultural events such as the Corralejas has aroused interest and debate. Among the numerous testimonies collected, evidence has been repeatedly identified regarding the bulls that were in the arena at that time and how they were petrified, showing an unusual and unexpected reaction to human presence.

|

I threw myself to the sand and the bulls stayed still because I passed by them. There were three bulls, I passed by them, three black bulls. I was scared when I passed by them, but no, they stayed still, people were passing by and I passed by them, I found them in front of me. (SP20, personal communication, September 22, 2022, own translation). |

|

That was total panic, people desperate to get away. There is a case of a friend who was in a side box, she was young and very active, a quite empowered woman as they would say now, and she jumped from the second level, she jumped into the ring, she fell in front of a bull and the bull did nothing to her, she moved and left. (SP11, personal communication, August 3, 2022, own translation). |

|

Suddenly, I heard the roar, and I sat down. The first thing I did was put my hands on my legs to see that I had them. I was scared when I realized that I was inside the square where the four Miura bulls were, but they were petrified. They did not move from their place. (Merlano, 2022, p. 114) (own translation). |

|

Even the bulls themselves were surprised. Not even the bulls moved. It were as if they were surprised too. (SP16, personal communication, August 2, 2022, own translation). |

According to these stories, the bulls that remained motionless and petrified in the presence of people who passed near them is a constant. Testimonies describe how the black bulls stood still when people walked past them, even in front of them. A specific case is mentioned in which a person threw herself into the ring in front of a bull and it did not harm her. Another witness recounts how the bulls did not move from their spot despite the commotion and noise in the bullfighting ring.

As part of the SRs of the 1980 tragedy, the evidence presented below sheds light on the dynamics of the events, focusing on the issue of burials and the deep significance that the cemetery acquired as a sacred setting after the tragedy.

The cemetery became a significant space in the Corralejas tragedy and acquired sacred importance for the community. It was the scene where the collective rite was carried out, in which the people said goodbye to the deceased, and the mourners expressed their mutual condolences. El Charcón street, which connected the church with the Sincelejo Central Cemetery, became a procession of coffins. A witness recounts how he witnessed a long line of coffins, one after another, stretching along the street. The crowd was overwhelming, with an even larger attendance than in Corralejas themselves. These testimonies reveal the complexity and emotional burden associated with this crucial aspect of the traumatic experience.

To obtain the central memory, a review of all the speeches collected throughout the research was carried out. Specifically, the interviewees were asked the following question: When you remember the Corralejas of 1980, what is the first thing that comes to mind? Here are some of the answers:

|

A lot of pain and anguish was experienced that afternoon, my friend Luz Marina lost two sisters that fateful afternoon, and her mother from that day on, was never the same. For all that I do not share this Corralejas party, they remind me of pain, a lot of pain and sadness. (SP17 personal communication, July 7, 2022, own translation). |

|

Today, after that horrible day, where the blood and mud were caked on my new clothes, and in the midst of so much pain, the terrifying screams of those who were lying under the boards asking for help to be taken out. They died trampled by the human stampede. Agony, of those who wanted to save themselves [...]. I remember seeing many who did not help, but rather took advantage of it to rob even those who asked for help, sadness that amid so much pain the heart of many were not moved. I remember that I got on a truck that was picking up the injured or dead and we took them to the hospital and came back again, this was horrifying. (SP21, personal communication, March 5, 2022, own translation). |

|

They threw out the dead people like they were pigs, I was about 10 years old when that happened, they threw them out the doors of the house like pigs. Around my house, about five families had a dead person each, the police trucks threw them like that. (SP22, personal communication, September 22, 2022, own translation). |

|

I was inside the Corraleja […] when they collapsed. We were stunned for a while and then I went to help with the wounded, but I was nervous. I found a bottle of brandy and I drank half a bottle for my nerves and started helping to look for relatives and other people. I saw it up close, such mortality, people asking for help and others already deceased. (SP09, personal communication, March 18, 2022, own translation). |

|

When I remember the Corraleja of 1980, I remember all the things I experienced because I was a girl, and you know that when you are a child, the disaster that occurred is recorded in you: Deaths, people mourning, dead family, the people who even remained "unnamed" because they did not know what countries they were from. People came from many countries, so there in the cemetery there remain people who were never claimed because they did not know if they were in Colombia. January 20 was an immense thing, very important even for the country, then tragedy comes to me that's why I don't like Corralejas, they seem like an archaic, old thing, from old times, from the last century (SP22, personal communication, September 22, 2022, own translation). |

|

I saw how the children were skewered on [the stakes] […] that's why I don't like Corralejas, to me they seem like an archaism, from old times and I saw how the children were fried, the pots, little children, one-, two-years-old. (SP22, personal communication, September 22, 2022, own translation). |

|

My mother, upon hearing the noise and sirens of the cars carrying the wounded, ran to the hospital to help care for the wounded. At that moment, she could not leave me anywhere else but take me with her. I can’t forget that image, I have always thought about drawing it. When we passed the door after the reception, there were the dead, one after another in the hallway, covered with sheets. A policeman and a nun were talking next to the dead, there was one with his face uncovered. He was a dark-skinned man with a sharp nose. His face was bloodied. The shock was such, that I will never forget it. I don't remember anything else about that day. My mother left me with the nuns and went to tend to the wounded, a slaughter. (SP26 personal communication, July 26, 2022, own translation). |

|

Around me I saw dead, wounded people, crying. I got nervous, I got up and ran to flee the place and I came to a small bridge. I looked back and could see the boxes that had fallen. The scene was gruesome. At that moment was when I started to feel strong pain in my chest, but I had no injuries. I felt another pain in my left heel caused by a wound. (Merlano, 2022, p. 115) (own translation). |

First, the testimonies reveal the theme of trauma and emotional pain as dominant elements in the participants' memories. The losses of loved ones and the lasting impact on the lives of those affected are mentioned repeatedly, and the suffering experienced is evident.

Second, violence and death are highlighted as intrinsic aspects of the Corralejas, where testimonies describe graphic scenes of people being trampled, skewered on stakes and dying in the middle of the crowd. These stories convey the brutality that was experienced that fateful day. Third, a sense of dehumanization is observed in the testimonies, since the bodies of the victims were treated as objects or animals. There are cases of bodies thrown like pigs, and of unidentified people who were not claimed. This phenomenon reflects a loss of dignity and respect toward those affected.

From the study of the social networks of the inhabitants of Sincelejo, regarding the Corralejas tragedy of 1980, six categories were identified that reflect the beliefs, perceptions, and collective memories associated with this event. These categories emerge through the analysis of the evidence collected, and provide a detailed vision of the SRs around the tragedy.

In this sense, social networks play a fundamental role in the interpretation and understanding of momentous events in a community. In this case, popular beliefs, testimonies, and empirical evidence allow individuals to make the physical and social reality that surrounds them intelligible. The SRs about the Corralejas tragedy are connected, in this case, with magical thinking, conceived as

Characteristic of man's external behavior to achieve control of nature, promoting the realization of his desires, but also serves to achieve mastery over himself by reducing anxiety, resorting to magical thinking that allows him to control what he perceives as uncontrollable. (Petra-Micu & Estrada-Avilés, 2014, p. 29, own translation).

In this way, the society of Sincelejo of 1980, whose features contradict modernity, or, as Hernández (2013) says: "the premises of modernity have never been fully appropriated" (p. 159), rely on the powers of the imagination to construct narratives and symbols that helped them make sense of the unexplained.

For the people of Sincelejo, the tragedy in the Corralejas was surrounded by signs and premonitions that awakened the belief in a bad omen caused by the upheaval of tradition as a warning of imminent danger. These beliefs and superstitions rooted in the community, highlight the role of social networks in the interpretation of events and in the construction of shared meanings. The study of these phenomena allows understanding how individuals make reality intelligible, and how collective beliefs influence the perception and anticipation of transcendental events. In this context, SRs emerge as an organized body of knowledge derived from magical thinking that allows individuals to integrate into their social environment, interpreting the physical and social reality in which they are immersed.

Although modernity is distinguished by adopting a rational, scientific, reflective, and analytical perspective, different forms persist “of profane mystification, as well as expressions of rituality that, under multiple modalities, are evident in the secularized environment” (Machuca, 2015). In this order of ideas, Johnson (2015) affirms that the modern world has not completely "disenchanted"; magical thinking is still present despite globalization and the dizzying advances in science and technology.

These popular stories and perceptions reinforce the idea that Arturo Cumplido and the Corralejas tragedy were enveloped in a mysterious and superstitious atmosphere. Mainly because it is speculated that Cumplido had a pact with the devil, and the denial he was subjected to regarding the delivery of the bulls generated the fall of the boxes, which became a symbolic explanation to understand a tragic event. Likewise, prior warnings, such as the torrential downpour and the politicization of the festivities, fueled the perception of a bad omen and generated expectations of a disastrous event.

These stories and popular beliefs reveal the fundamental role of social networks in the interpretation and construction of meaning through the creation of symbolic narratives to understand and explain transcendental events. These SRs, rooted in the collective imagination, allow individuals to make the physical and social reality that surrounds them intelligible, as well as integrate them into a group and with them, establish daily exchange relationships. Consequently, the study of SRs in the context of historical and cultural events reveals the complex interaction between shared knowledge, beliefs, and individual and collective psychic processes.

In this sense, on many occasions, people act far from logic and rationality. Instead, they opt for superstitions, prejudices, quackery practices, horoscopes, and magical rituals, among others (Pérez, 2004), which contradict rational logic and position themselves in magical thinking to respond to extraordinary situations. For this reason, the testimonies cited here maintain the tendency to favor information that confirms their pre-existing beliefs about objective and verifiable facts, which leads to decisions and behaviors in everyday life being more influenced by personal beliefs than by objective and reliable data.

These findings point to the existence of an unusual meteorological phenomenon and suggest the presence of symbolic and supernatural elements associated with the tragedy. The isolated rain, concentrated only on the corraleja area, raises questions about its origin and possible influence on the event. Furthermore, in the video referred to by Movilla (2003), a visual narrative is revealed that hints at a connection between the dark sky, the lightning that resembles bull horns, and the subsequent fall of the boxes. These visual and symbolic elements awaken the imagination and speculation about the existence of supernatural forces involved in the tragedy.

However, keeping in mind that the analysis of social networks does not aim to provide definitive or scientific answers to the phenomena studied, but rather to explore the perceptions, beliefs, and meanings that arise in a specific community is important. In the case of the tragedy in the Corralejas, the SRs reveal the complexity and richness of popular interpretations around isolated rain and its possible relationship with supernatural forces.

In the three emerging categories identified: premonitions or bad feelings, popular stories and legends, and isolated rain, a marked predominance of magical thinking over rational thinking is observed. A clear example of this is the engineering explanation for the collapse of the Corralejas, attributed to specific factors such as: (1) the intense rain that fell that afternoon, (2) which weakened the foundations of the structure, and (3) the overload of the structure caused by the excessive sale of seats. However, faced with this technical explanation, the collective imagination chooses to attribute the tragedy to supernatural causes, which highlight the persistence of mythical beliefs and explanations in the understanding of events.

Human-animal interaction during the Corralejas has revealed "extraordinary" phenomena, such as the petrification of bulls in the face of human presence. Testimonies collected during the tragedy provide evidence of bulls remaining motionless in the proximity of people, even in dangerous situations, and raise questions about the possible reasons behind this unexpected behavior.

In this framework, it is necessary to bring up Martínez (2018):

The connection of the bourgeois elites of Sincelejo with the cultural practices of the Corralejas, shows a particular ambiguity that occurs in the process of Latin American modernity, in comparison with the European phenomenon. The idea of modernity and progress calls for the disappearance of strong emotions as a manifestation of civility, a premise that cannot be fully addressed by the elites of Sincelejo, by maintaining their attachment to the enjoyment of bullfighting, death and "barbarism." (p. 174, own translation).

The relationship between man (street vendors, cape makers, bullfighters) with the bull, manifests an identification of strength, virility, and bravery. At these parties, both experts and inexperienced, confront the animal and challenge it to attack them. However, there is also a manifest rejection on the part of a sector of the population, as stated by interviewee SP22:

The rancher throws [money] only and exclusively when the bull is down there, underneath it, he throws it at the bull, then people run, that is a danger, and it seems to me that it is even a murder by part of the rancher. (SP22, personal communication, September 22, 2022, own translation).

The stories reveal the symbolic importance of the cemetery as a place of collective meeting and expression of mourning. The fact that the cemetery was packed with coffins and that the community gathered around this striking image, demonstrates the human need to impart collective meaning to suffering and loss. The cemetery becomes a sacred space where emotions are channeled, and a spiritual bond is established with deceased loved ones.

The image of the procession of coffins and the daunting task of burying so many people in a short period of time highlights the magnitude of the tragedy and the emotional impact it had on the community. The smell of the cemetery impregnated with the presence of 300 lifeless bodies adds a sensory dimension to the pain and mourning experienced.

For Torres (2006), funeral rituals “represent the ways of life of a society, with the expression of eternal truths, achieving the establishment of unity and cultural integration” (p. 109, own translation) and its objective is to provide a framework, organization and meaning to human life through regular, formal and participatory ceremonies, which are distinguished by their close relationship with symbolic elements. Many people from different cultures find in these practices a way to impart meaning to an act of life, intending for it to have a transcendental scope. Therefore, the act concerns the person who performs it, and also collectivizes the action through a shared meaning, and reinforces values such as solidarity and unity (Acosta et al., 2023).

Ultimately, this evidence highlights the importance of funeral rituals and sacred spaces in the construction of the social representation of death and mourning. The cemetery becomes a place of collective gathering and spiritual transcendence, where the community finds comfort and a sense of continuity in the midst of pain and loss. The study of these SRs in the context of the Corralejas of Sincelejo, shows the importance of funeral rituals as fundamental elements for the reconstruction of the social fabric and the elaboration of mourning in moments of collective tragedy.

The testimonies reveal that the experience of the Corralejas of 1980 in Sincelejo was marked by death, pain, and trauma, since they still reflect the emotional impact caused by the loss and suffering experienced by those affected. In addition, graphic scenes of violence and death are described in the middle of the Corralejas, added to the dehumanization in the way in which the bodies of the victims were treated, dumped, or left unidentified or unclaimed. These testimonies also raise a social criticism of Corralejas, questioning their cultural and moral value due to the cruelty and inhumanity associated with this practice. Together, these central elements in the discourses highlight the need to reflect on the violence, suffering and transformation of this cultural tradition.

The study of social networks in the context of historical and cultural events allows understanding the way in which people interpret and construct meanings in their environment. In this sense, Jodelet (1986) states that:

The notion of social representation places us at the point where the psychological and the social realms intersect. First of all, it concerns the way in which we, social subjects, apprehend the events of daily life, the characteristics of our environment, the information that circulates within it and the people in our immediate or distant environment (p. 473, own translation).

The study of SRs connects with the theory and the proposed method, since the symbolic construction of an event intersects with the collective notion of the event itself.

In Colombia—as in other countries—parties, festivals and fairs are promoted as a country brand and are part of the collective imagination (Betancourt, 2023, p. 182). In this sense, Fals (2002a) states that, from the beginning, in this type of festivals, people from all strata are present: “mixed without distinction, to do their foolish things; and even the rich women, wives and daughters of landowners, went out to the streets to set up tables to sell sweets and liquor” (p. 155).

The Corraleja festivity, likewise, brings together the population from different social strata, and combines religion, music, dance, local gastronomy, and commerce. In short, the idiosyncrasy of the Sincelejo people, their values, beliefs, and customs (Sánchez, 2007) serve as a collective catharsis, as described by Fals (2002b):

To alleviate social tensions, encourage popular recreation, and provide opportunities for individual expansion and distinction to the exploited and marginalized workers in front of the elitist culture of the savannas—apart from horse racing, machete fencing, and similar sports—the famous bullfights today called “Corralejas” were developed (p. 96, own translation).

In this context, the dimension of the tragedy in the Corralejas of 1980 can be understood more broadly; as well as the construction of social networks that explain the contradictions of a cultural tradition that collides with modernity, and that revealed the political game that perpetuates colonial power (Hernández, 2013), and also justifies this type of celebrations on account of heritage preservation. Consequently, the collective town was marked in a before and after in its imagination with, according to the evidence collected, associated magical and symbolic elements, which raises questions about its origin and its relationship to the tragic event.

Magical thinking, closely linked to the sacred and the irrational in interpretation of Eliade (2022), reflects how tragedy and the world, or the "enchanted world," are perceived through a mythification of reality. This vision, socially shared, is an intrinsic part of the idiosyncrasy of the Colombian Caribbean coast and of Latin America in general.

In this line of thought, death, invariably associated with the sacred, represents a conclusion of the life cycle. The experience of collective death, or the collectivization of mourning, serves to attenuate individual pain. The solidarity of the people, manifested during the funeral ceremony, facilitated the process of collective mourning. At this event, families of the victims gathered, shared condolences and comfort. This showed that the pain and trauma transcended the personal realm, to become an experience shared by the entire community of Sincelejo, immersed in sadness due to the tragic outcome of its most important festival and the most notable Corraleja of the time.

Furthermore, these observations challenge traditional conceptions of the relationship between humans and animals, and invite rethinking the way in which humans understand each other, and how they relate to other species in cultural events and social contexts. The study of these SRs enriches the understanding of how individuals make physical and social reality intelligible, and how beliefs and imagination influence the interpretation of events that defy rational understanding. In this sense, a study of the sacred and the profane associated with the Corralejas tragedy of 1980 in Sincelejo is necessary.

Acosta, K., Sierra, A. M., Barboza, J. L. & Montenegro, S. (2023). Ritos funerarios y experiencias de duelo en el pasado y durante la pandemia por COVID-19: Ritos funerarios y Duelo. Revista Colombiana de Ciencias Sociales, 14 (2), 760-783. https://doi.org/10.21501/22161201.4247

Arrieta, Y. K. & Díaz, K. E. (2010). Fiestas de Corralejas en Sincelejo: Cultura, economía y política, 1966 – 1980 (Tesis de grado). Universidad de Cartagena, Colombia. https://repositorio.unicartagena.edu.co/handle/11227/288

Betancourt, M. (2023). Simulaciones visuales de la identidad. Divergencias entre imaginarios y representaciones en Colombia (Tesis de doctorado). Universidad Externado de Colombia, Bogotá. https://bdigital.uexternado.edu.co/entities/publication/428bb89e-77a0-44f8-97c6-e7b45e545c71

de Alba, M. (2012). A Methodological Approach to the Study of Urban Memory: Narratives about Mexico City. Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 13 (2), 1-20. https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-13.2.1854

Eliade, M. (2022). Lo Sagrado y Lo Profano . Paidós.

En enero siempre llueve. (1 de diciembre de 2021). ¿Qué pasó el 20 de enero de 1980? [Archivo de video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9z87ovPxDpM

Fals, O. (2002a). Historia doble de la Costa . Tomo I. Mompox y Loba. Universidad Nacional de Colombia. Banco de la República. El Ancora.

Fals, O. (2002b). Historia doble de la Costa. Tomo IV. Retorno a la tierra . Universidad Nacional de Colombia. Banco de la República. El Ancora.

Flórez, A. G. (2008). El poder de la carne: Historias de ganaderías en la primera mitad del siglo XX en Colombia . Editorial Pontificia Universidad Javeriana.

Gómez, A. (January 21, 2020). Memoria viva de aquel 20 de Enero [Audiovisual description]. Facebook. https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v=177902756610536

Hernández, A. A. (2013). La Fiesta en Corralejas: Las contradicciones de un patrimonio no patrimonializable. Boletín de Antropología, 28 (46), 143-160. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/557/55730873008.pdf

Jodelet, D. (1986). La representación social: fenómenos, concepto y teoría. In S. Moscovici (Ed.), Psicología Social II : Pensamiento y vida social (pp. 469-494). Barcelona, Páidos.

Johnson, A. (2015). Introducción. Magia y modernidad. Dimensión Antropológica, 63 (22), 41-69. https://www.dimensionantropologica.inah.gob.mx/?p=12492

Ley 1272 de 2009. Por medio de la cual se declara Patrimonio Cultural de la Nación la Fiesta en Corralejas del 20 de enero en Sincelejo, y se hace un reconocimiento a la Cultura del Departamento de Sucre y se autorizan unas apropiaciones presupuestales . Enero 5 de 2009. DO: 47223.

Machuca, A. (2015). El pensamiento mágico en el mundo secularizado. Dimensión Antropológica, 63 (22), 41-69. https://www.revistas.inah.gob.mx/index.php/dimension/article/view/7650/8514

Martínez, G. (2018). La Plaza Principal de Sincelejo . Editorial CECAR.

Merlano, A. (2022). Escarbando mis huellas . Sincelejo Arte y Creatividad.

Moscovici, S. (1979). El psicoanálisis, su imagen y su público . Huemul.

Movilla, L. E. (2003). Corraleja. Solo Dios es culpable . Tipografía Duplicar.

Niampira, A. & Barguil, J. A. (2021). La Corraleja: Representación arquitectónica desde la tradición e historia del Caribe en Colombia. Revista Mimesis, 1 (1), 113-136. https://doi.org/10.56205/mim.1-1.6

Pérez, J. (2004). Las Representaciones Sociales. En Páez, D., Fernández, I., Ubillos, S. y Zubieta, E. M. (Coords.) Psicología Social, Cultura y Educación (pp. 413-442). Pearson Prentice Hall.

Petra-Micu, I. & Estrada-Avilés, A. (2014). El pensamiento mágico: Diseño y validación de un instrumento. Investigación en Educación Médica, 3 (9), 28-33. https://doi.org/10.22201/fm.20075057e.2014.09.00005

Sánchez, M. L. (2007). La fiesta patronal en San Francisco Caltongo: Identidad y representaciones sociales (Tesis de maestría). Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana de México, Ciudad de México. https://repositorio.xoc.uam.mx/jspui/handle/123456789/26407

Strauss, A. & Corbin, J. (2002). Bases de la investigación cualitativa. Técnicas y procedimientos para desarrollar la teoría fundamentada (2.a ed.). Editorial Universidad de Antioquia.

S/a (February 11, 1980). Arturo Cumplido y el 20 de Enero. El Cenit.

Torres, D. (2006). Los rituales funerarios como estrategias simbólicas que regulan las relaciones entre las personas y las culturas. SAPIENS, 7 (2), 107-118. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/410/41070208.pdf

Turbay, S. (1995). De la cumbia a la corraleja: El culto a los santos en el bajo Sinú. Revista Colombiana de Antropología, 32 , 6-40. https://doi.org/10.22380/2539472X.1375

1 This article is part of the project: “The Central Cemetery of Sincelejo, a Cultural History 1878-1985. Social Representations in Letters and Photography," with code 72111. Financing: Received funding from the National Program of Science, Technology and Innovation in Social Human Sciences and Education of Minciencias, Colombia. Declaration of interests: The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest. Data availability: The data is found in the “Sincelejo Central Cemetery” repository.

2 PhD in Education. Research professor at the Corporación Universitaria del Caribe – CECAR, Colombia. Member of the IDEAD Research Group. Universidad Pedagógica Experimental Libertador, Venezuela. Email: yildret.rodrigueza@cecar.edu.co

3 PhD in Education. Research professor at the Corporación Universitaria del Caribe – CECAR, Colombia. Member of the IDEAD Research Group. Universidad Nacional Experimental Rafael María Baralt - UNERMB, Venezuela. Email: jorge.barbozah@cecar.edu.co

4 Ph.D. in Educational Sciences. Research professor at the Sergio Arboleda University, Colombia. Member of the Cicosvida Research Group. Email: nubia.hernandez@usa.edu.co

5 Doctor in Psychopedagogy. Research professor at the Institución Universitaria de Envigado, Colombia. Member of the PAYS Research group. Email: eklimenco@correo.iue.edu.co