Bio-learning Based on Community Experiences in a Rural Territory of Colombia1

Bioaprendizajes gestados desde las experiencias comunitarias en un territorio rural de Colombia

Bioaprendizagem gerada de experiências comunitárias em um território rural da Colômbia

Received 19 May 2023

Accepted August 2023

|

How to cite Suárez, I.Y., & Tobón, G.C. (2024). Bio-learning Based on Community Experiences in a Rural Territory of Colombia Ánfora, 31(57), 23-48. https://doi.org/10.30854/anf.v31.n57.2024.1083 |

Ingrid Yised Suárez Ortiz2 https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5338-0719 CvLAC https://scienti.minciencias.gov.co/cvlac/visualizador/generarCurriculoCv.do?cod_rh=0000129154 Colombia Gloria del Carmen Tobón Vásquez3 https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5338-0719 CvLAC https://scienti.minciencias.gov.co/cvlac/visualizador/generarCurriculoCv.do?cod_rh=0000145262 Colombia |

Objective: To base bio-learning on community experiences in a rural territory of Colombia. Methodology: A socio-critical paradigm, qualitative approach, and Critical Participatory Action Research (CPAR) method. Instruments were a sociodemographic survey, focal groups, semi-structured individual interviews and learning experiences. The instruments were supported by the sociodemographic sheet, focal groups and interview scripts, planning of learning experiences, and observation sheets. The work unit was 51 community families, six teachers, 29 students, six community-linked external agents and one research professor for a total of 195 participants. Results: In Cycle I Problematization, the disconnection of the school from the community was recognized due to the lack of recognition of ancestral local knowledge from the culture, customs, and traditions of the community. Cycle II Communitization was implemented to enable the solution of those problems. It was based on three learning experiences related to coffee as the main product of the rural territory. As a result, community-related processes such as the construction of peasant and school knowledge supported by processes of community bio-learning were found to provide an ideographic vision of communitization. The community is constructed in a shared pedagogical environment in which bio-community learners interact as part of a bio-learning community to solve the needs of communitization and project bio-learning. Conclusions: Customs have not passed from generation to generation; neither daily life activities nor the value of bio-learning are being exploited. The learning spaces can be found in everyday life, in nature, or in the rural territory itself; hence, the importance of learning experiences from community participation-based bio-learning. The bio-learning community is recognized as supported by community training processes in, from, and for life. It takes the indigenous, cultural, customs, what is shared from the territory, and what has been referred to as the community spirit of bio-learning as its starting point.

Key words: Learning; bio-learning; rural territory; community experiences; learning experiences; bio-community (obtained from the UNESCO and ERIC thesaurus).

Resumen

Objetivo: gestar bioaprendizajes desde las experiencias comunitarias en un territorio rural de Colombia. Metodología: paradigma sociocrítico, enfoque cualitativo y método de Investigación Acción Participativa Crítica (IAPC), utilizando como técnicas la encuesta sociodemográfica, grupos focales, entrevistas individuales semiestructuradas y experiencias de aprendiencia. Cada uno con sus respectivos instrumentos, ficha sociodemográfica, guion de grupos focales, guion de entrevistas, planeación de las experiencias de aprendiencia y fichas de observación. La unidad de trabajo estuvo conformada por 51 familias de la comunidad, seis enseñantes, 29 estudiantes aprendientes, seis agentes externos vinculados a la comunidad y una enseñante investigadora, para un total de 195 personas. Resultados: en el ciclo I de problematización, se reconoció como principal problemática la desvinculación de la escuela con la comunidad debido a la falta de reconocimiento de los saberes ancestrales, locales, desde la cultura, costumbres y tradiciones comunitarias. El ciclo II de comunitarización se aplicó para posibilitar la solución de las problemáticas encontradas, a partir de tres experiencias de aprendiencia relacionadas con el café como producto principal del territorio rural. En consecuencia, se encontró que los procesos comunitarios relacionados mediados por la construcción de saberes campesinos articulados a los conocimientos escolares, agenciados por procesos de formación comunitaria bioaprendiente, brindan una visión ideográfica de comunitarización. Lo comunitario se construye en un espacio pedagógico compartido en el que interactúan los aprendientes biocomunitarios, en una relación de pertenencia a la comunidad bioaprendiente, para dar solución a las necesidades de comunitarización y generar una proyección de aprendizaje bioaprendiente. Conclusiones: no se han trasmitido las costumbres de generación en generación; tampoco se están aprovechando las actividades cotidianas, elementos valiosos para la gestación de bioaprendizajes, dado que estos espacios de aprendiencia se pueden dar desde la cotidianidad, desde lo natural, en el propio territorio rural. Por ello, la importancia de las experiencias de aprendiencia en donde desde la participación comunitaria se gestan bioaprendizajes. Se reconoce que la comunidad bioaprendiente se sustenta por procesos de formación comunitaria, es decir, la formación vital en, desde y para la vida, teniendo como punto de partida lo autóctono, lo cultural, las costumbres, lo que se comparte desde el territorio, lo que se ha denominado como espíritu comunitario bioaprendiente.

Palabras clave: Aprendizaje; bioaprendizaje; territorio rural; experiencias comunitarias; experiencias de aprendizaje; biocomunidad (obtenidos del tesauro de la UNESCO y ERIC).

Resumo

Objetivo: gerar bioaprendizagem por meio de experiências comunitárias em uma região rural da Colômbia. Metodologia: adotou-se o paradigma sociocrítico, uma abordagem qualitativa, e o método de Pesquisa de Ação Participativa Crítica (CPRAR). Para isso, foram utilizadas diversas técnicas, tais como pesquisa sociodemográfica, grupos focais, entrevistas individuais semiestruturadas e experiências de aprendizagem. Cada uma dessas técnicas foi acompanhada de seus respectivos instrumentos, incluindo ficha sociodemográfica, roteiros para grupos focais e entrevistas, planejamento das experiências de aprendizagem, bem como fichas de observação. A unidade de trabalho foi composta por 51 famílias da comunidade, seis professores, 29 alunos, 6 agentes externos vinculados à comunidade e 1 professor-pesquisador, totalizando 195 pessoas. Resultados: no primeiro ciclo de problematização, identificou-se como principal questão a desconexão entre a escola e a comunidade, resultante da falta de reconhecimento do conhecimento ancestral e local da cultura, dos costumes e das tradições comunitárias. O Ciclo II de comunitarização foi então aplicado para abordar esses problemas, com base em três experiências de aprendizagem relacionadas ao café, principal produto do território rural. Como resultado, observou-se que os processos comunitários, mediados pela integração do conhecimento camponês com o conhecimento escolar e conduzidos por meio de treinamentos comunitários em bioaprendizagem, proporcionam uma visão ideográfica da comunitarização. A comunidade é assim estabelecida como um espaço pedagógico compartilhado, onde os alunos da biocomunidade interagem em um ambiente de pertencimento à comunidade de bioaprendizagem, visando oferecer soluções para as necessidades de comunitarização e promover um ciclo contínuo de aprendizagem em bioaprendizagem. Conclusões: evidenciou-se a interrupção na transmissão de costumes de geração em geração, assim como a subutilização das atividades cotidianas como elementos valiosos para o desenvolvimento da bioaprendizagem. Tais espaços de aprendizagem podem ser facilmente criados a partir da vida cotidiana e da interação com a natureza, dentro do próprio contexto do território rural. Destaca-se, portanto, a importância das experiências de aprendizagem que promovem a bioaprendizagem por meio da participação ativa da comunidade. Reconhece-se que a comunidade de bioaprendizagem é sustentada por processos de formação comunitária, caracterizados por uma educação vital na, da e para a vida, centrada nos aspectos indígenas, culturais e nos costumes compartilhados no território. Este fenômeno foi denominado de "espírito comunitário de bioaprendizagem".

Palavras chave: Aprendizagem; bioaprendizagem; território rural; experiências comunitárias; experiências de aprendizagem; biocomunidade (extraído do tesauro da UNESCO e do ERIC).

Introduction

This article is part of the research carried out within the framework of the Doctorate in Education of the Catholic University of Manizales to generate bio-learning from community experiences in La Eureka, Huila, Colombia. It aims to strengthen learning through the link between the curricular knowledge of the school and the knowledge owned by community actors (henceforth referred to as bio-learning). This promotes the recognition of the culture, traditions, relationships, and experiences in the territory, through community experiences of learning from everyday life.

The rural territory is the stage for promoting community experiences. They enable social practice in connection with the school, where learners achieve bio-learning to improve their reality. For Fals Borda (cited by López, 2006) the territory is not understood only as a geographical area, but as a symbolic place of interactions between the members of the community and collective actions in the house lived in. Escobar (2014) explains that the territory constitutes the axis in the constitution of the world; it includes the land and its ecosystems, as well as the processes of territorialization that based identities and appropriations. This means that territory is a “life project,” according to Romero (2012) is a territory that covers rural areas and rurality as well as new rural areas.

In rural areas, promoting community experiences through learning experiences as a process based on meeting others and relating school knowledge to their own community knowledge is vital. Building knowledge is only possible to the extent that the school is linked to the rural context from the reality of the learners, a knowledge of what has been lived and inspired in the future of living (Contreras & Pérez, 2010). The project aims to foster bio-learning in students within a time and a space, from their vital niches, interactions with the community and the environment, and understanding that essential and cognitive processes are similar (Assmann, 2002). Critical experiences promote personal and collective transformations and participants building their own learning (Woods, 1998).

Parra et al. (2019) state that one learns in, from, and for life, from networks of interaction with others and with the environment. Bio-learning as a possibility for developing the condition of humanity for those who learn is to self-organize, to have new knowledge, and transform it into their daily lives. Gutiérrez (2010), states that promoting learning experiences allows the learner to learn in life itself with joy, and from their own interests.

In the state of art, researchers refer to community experiences; their epistemological approach is the socio-cultural and linguistic diversity of indigenous peoples, the community art experiences, community participation, school contents, student roots, families, field education, local knowledge, and community education (Pérez & Cárdenas, 2020; Bolaños, 2021; Matei et al., 2022). Research has shown that the core fields of study are families, local knowledge, rural schools, and community engagement. The problematic issues in these publications refer to the gap between the school and its contents with the communities, and the proposals that are woven create projects that articulate local knowledge with the lessons learned from the rural school curriculum.

Research articles regarding bio-learning approach the perspectives of emotional education, learning for life, and narratives, among others (Funke, 2020). Ocaña and Reyes (2019) also involved musical experiences in the training of social identities in their qualitative research. Takeuchi et al. (2020), from a qualitative analysis, state that teachers demonstrate shared behavior through the exchange of knowledge with their peers and improve organizational capacities and teamwork. Teachers must create environments in which to share knowledge, complement that knowledge with new technologies, and establish relationships to foster teachers' learning and strengthen students' learning.

Those created environments must establish a close connection with the community and their rural territory to base solid and meaningful learning. Vera (2019) reveals that the rural school must relate community and territory for the memories, connections, and life experiences that are of great value, recover and put them in a new perspective from the school that demands to be territorialized.

The current rural school has pros and cons to understand as it is intended to conduct research in these educational spaces, mainly in rural areas of the country. Gonzáles et al. (2020) point out that the teaching reality and the rural schools have weaknesses but also strengths when the State provides resources, facilities, and little or no training to this type of institution.

Based on this, that the related findings were able to respond satisfactorily to the research question can be inferred. The question posed seeks to generate community experiences by enabling bio-learning in the community of La Eureka, in the rural territory of Tarqui in the department of Huila.

In this way, this article contains several sections, such as the methodology, constructed from the socio-critical paradigm, the qualitative approach and the CPAR method. It aims to improve the life realities of the bio-learning community through two cycles: problematization and communitization. These cycles allow the recognition of needs and the development of community experiences through bio-learning in this rural territory.

Methodology

From a socio-critical perspective, daily practices from the realities of rural lives, or agricultural participants, in the community of La Eureka in the municipality of Tarqui, Huila, are especially valued. In this way, research is created and develops socio-critically by being participatory, community-based, and emerging from the problems of the actors involved in the research (Habermas, 1986). Therefore, the building of knowledge is based on the popular knowledge owned by the people of the community.

A qualitative analysis enabled community interaction between families, students, teachers, community members, external actors sporadically involved, managers, and research teachers. In other words, the analysis intended to create a fabric between the school and the community to build bio-learning from the realities of the context. From this point of view, Bonilla and Rodríguez (2005) argue that the analysis is research based on the relationships of community participants, developed inductively from their realities.

The research methodology was carried out based on the Critical Participative Action Research method proposed by Kemmis et al. (2014). It links both social and educational issues and enables the participation of all actors involved in the research. Community training and improvement work was conducted based on the realities of the participants, from the actions of transformation that the same participants put forward with each other and other parties, and in reflection of their actions for the planning of community experiences that strengthened the work unit and the encounter between the community and school area for the construction of learning.

Work Unit

The learning community participating in the research process or work unit was composed of 29 learners, six apprentice teachers, one research professor, 51 families from the community, and six external actors for a total of 195 participants.

Methods

The research process carried out used a community-based participatory research (CBPR) method based on two cycles: problematization, and communitization. Both cycles considered the self-reflective spiral proposed by Kemmis and McTaggart (2013). This cycle referred to planning, action, observation, and reflection, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Cycles and Steps of Critical Participatory Action Research.

Cycle I: Problematization

The CPAR enables the improvement of the participants’ daily reality through their own reflections and their own actions as a community as one of the research goals, which is that participants identify their own problems. At planning, a sociodemographic survey was conducted to characterize the community. A proposal was also planned for initial focal groups with students, parents and mothers, the community, and teachers to problematize from their interests and reality. The preparation of semi-structured interviews to external community-linked actors was conducted, and the implementation of the problem tree and objectives. Then, in the action stage, the techniques were applied. The observation and reflection and data were systematized.

Cycle II: Communitization

The rural territory of La Eureka is a particular community-oriented context. Novoa and Camacho (2017) state they are relating to each other, the community, and other parties. Thus, participants promote the changing action of their community.

The learning experiences were generated as a process of building learning based on the encounters and unity among the community members. They give value to itself and link school knowledge with the popular knowledge of peasant people in the community. From group and community events to democratic, participatory processes, everyone learns and teaches at the same time.

There were three learning experiences: Eureka baila y canta, Los sabores de mi tierra and Los frutos de mi región. A meeting of those with school knowledge was promoted, and a specialized classroom was created for the collection of the results of the learning experiences.

The cycle started with the planning time and the community learning experiences of the community leaders. They planned each experience considering stages and guiding questions, a timetable, and the celebration of the day of learning in the community. At the time of the event, the lead group socialized and validated the plans cooperatively to implement learning experiences. The observation was conducted in parallel; this made visualizing the development of each of the experiences possible. Observation sheets were fulfilled by the researcher. The observation by the participants through reflective meetings was essential to identify strengths and opportunities for improvement and to rearrange actions into a new cycle in further research if it was of interest to the participants.

The analysis of the information was conducted through elementary qualitative analysis with SPSS, the community characterization by Atlas Ti software, version 9, and the use of Glasser and Strauss’ constant comparative method (1967). The theory was constructed empirically and inductively from the participants' reality through open, axial, and selective classification.

Results

Participant Characterization

The field work began with the sociodemographic survey of each of the 51 families of the community to cover 195 people and create a characterization of same. Through the meetings held in each of the households and the interaction with participants, the physical scenarios of the territory context, their lives, and the social realities of their culture, traditions, and customs are recognized.

Most of families had four members and very few just one. There were 57.4 men. The average age of females was 31.06 (SD=18.18%) and 26.87 for males. The ages ranged between 1 and 77 years.

The largest number of family members were in early adulthood (36.9 percent), and the fewest were in childhood and early childhood (4.1 percent). Education level was classified into groups of no degree (41.5); up to the fifth grade (14.4); and less in transition and technical level, each with one of the cases. The highest percentage (54.4) of family members are between preschool and eleventh grades.

The economic activities mainly involve coffee and other crops such as banana, yuca, vegetables and fruits. 19.5 do other activities.

Some people in the community have specific talents and feel qualified enough to teach others. One of the most important topics is agriculture (23.52%). Decoration, building, sewing, practicing sports, using technological tools, and environmental protection were the activities with the least participation (1% for each one).

Twelve people expressed their desire to learn how to cook. The responsibilities schoolchildren have in their families is mainly to study and do household chores (25 participants), five participants study and do farm work, and only 19 study exclusively.

Participatory Problematization with the Involved Learners

The research initially emerged from the interests of the researcher with categories from her perspectives. In this manner, the state of the art expanded the theoretical framework and community contributions. The categories of research are defined according to the needs.

However, in Cycle I, “Problematization,” three focal groups with students, teachers, parents, mothers, and people from the community were planned through the lead group. Six semi-structured individual interviews were also conducted with external actors of the community who are only sometimes involved in community activities. In this main, the main needs of the community were recognized, and the research objectives were established.

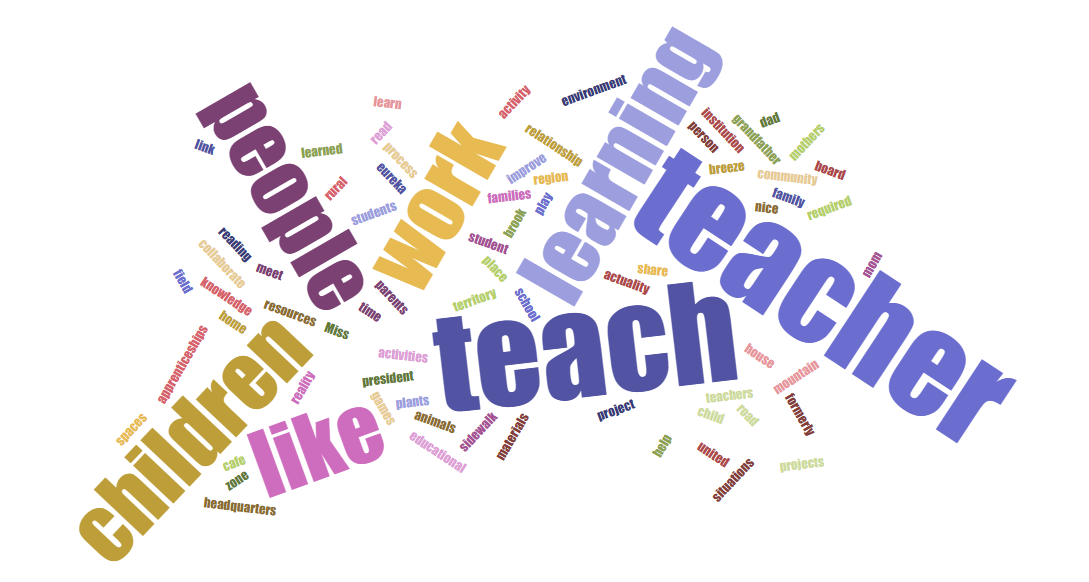

Through inductive analysis, the constant comparative method, and the realities and expressions of the participants, 46 codes were found in open coding. Rural territory, rurality, new rurality, rural school, country, region, mountains, territories, places, animals, creeks, environment, coffee, bio-learning, traditional learning, school learning, students, play, likes, life, share, reality, time, space, community experiences, activities, unity, work, collaborate, connections, home, past experiences, current experiences, situations, resources, materials, actors, parents, people, teachers, grandparents, students, mother, children, family, and children were the most remarkable issues (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Open Codification, Problematization.

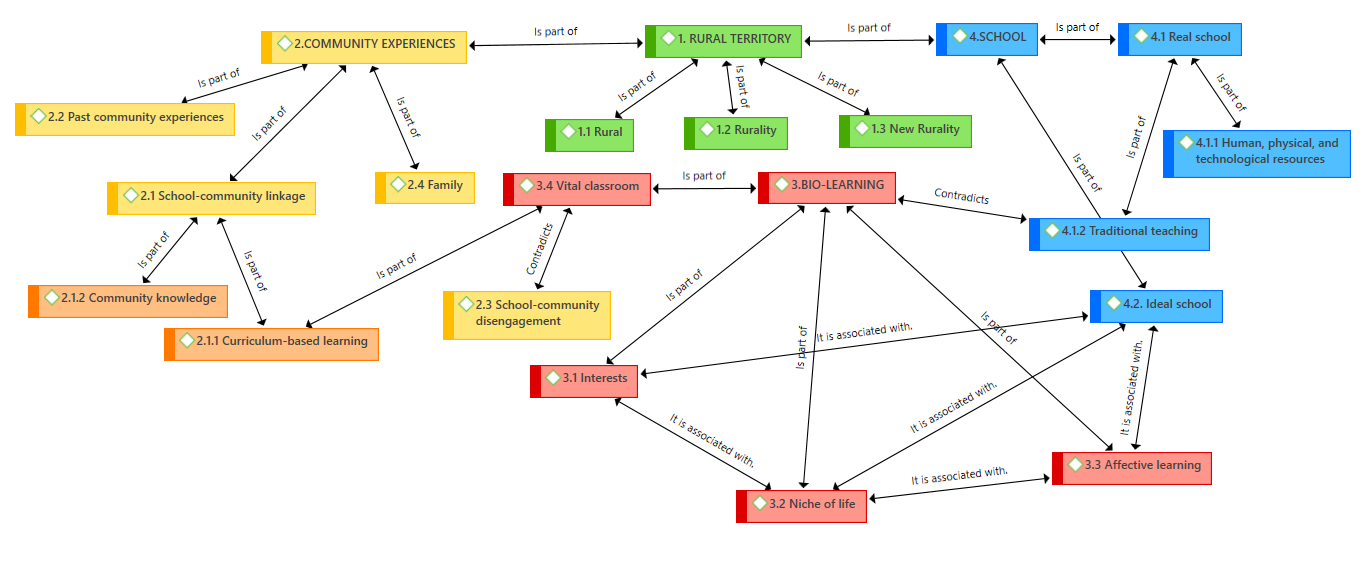

Based on a relational fabric between the different codes, they were grouped into categories and sub-categories: rural territory, community experiences, and bio-learning, with subcategories of rural, ruralities, new rural areas, real school, ideal school, school-community linkage, past community experiences, school and community disconnection, interests, life niche, affective learning, traditional teaching, lifelong classroom, school learning, and community knowledge.

The natural semantic network was created with the axial code:

Figure 3.Semantic Network of Problematization.

Rural territory, as a comprehensive category, covers rural, rurality, and new rural areas. The rural territory is the scenario in which the research is conducted and, at the same time, is linked to other scenarios of the same importance as community experiences, bio-learning, and school. It is seen as the space that impacts and not just one category of analysis.

A school is observed and understood in its reality with many traditionalist elements and whatever lack of resources, but, at the same time, as an ideal school for the participants. They would like to learn through their affection, the context of their daily and real-life experiences, and through their preferences. This makes bringing school knowledge closer to the knowledge of the people in the community possible.

The development of community experiences is encouraged by the implementation of learning experiences which are proposed and developed by the same actors who conduct the research, as they are the ones who really know their reality. This allows the construction of bio-learning. Therefore, reflecting on past experiences and, at the same time, improving on what has failed it is essential to.

Data gathered through the development of learning experiences is presented in the classroom, which is not just a four-walled space for children to learn. On the contrary, it is a classroom that extends to the lively scenes of the community of La Eureka, and to its rural territory. All conceptions of classroom were created to improve the affected connection between the school and the community.

The main problem found by community participants is the disconnection between school and community. The lack of relationship between school knowledge and community knowledge is important because there is a need for the recognition of everyday practices from culture and customs as part of learning. For this reason, everyday practices in the life niche are not considered a form of learning or teaching school skills since they are perceived as separate actions from the school, as the student state:

I was respirating a little chick and it died faster, we had to bury it, I was sad for helping it die faster. We did not like that it happened because we love animals very much. (Focal group No. 2, students, personal communication, 2022, own translation)

This experience is meaningful for the student since it represents the death of an important being to him. However, this experience has not been linked to community or school knowledge. For example, emotional management could be learned. As well as the community knowledge of animal care or customs related to death taking into account school content that can be linked such as the biological functioning of animals. However, this experience has not been linked to community or school knowledge.

Practices are understood as coming from the vital niche, the context in which they live, but they are not considered for building learning as part of school knowledge. One is thought to learn only in school and what is learned in everyday life is not considered valuable. Assmann (2002), from a cognitive ecology perspective, states that the construction of learning starts from vital niches, from community experiences.

The gap between ideas, beliefs, and customs between adults and children is also a problem. There is a total disconnect between children’s beliefs and the realities they live with their families in their homes, when there is not adequate articulation as to what is taught and learned in school. In this regard, Woods (1997) deals with critical community experiences articulating educational activities with events in everyday life.

Another problem concerns lost intergenerational practices that separate the school from the community. Parents’ caring practices today have changed considerably compared to the past expressing that the previous ones were better as they were founded on union, collaboration, and on the common welfare. The learner teacher expressed:

The parents are very young, they think only of work, sometimes they call me to tell the children that they are waiting for them somewhere because they are not at home, they are doing some kind of work; they do not realize what children do in school, nor do they check their tasks; we could say that they don't know about the activities their children perform, I see that children are very alone, that there is no support from the parents because they have dedicated themselves to work. (Focal group No. 1, learner teacher, personal communication, own translation)

Parents in early adulthood are more devoted to economic matters than to building a heritage. They leave aside the training and their intervention in the learning processes of the learners. Customs have not been passed from generation to generation, and parents are not taking advantage of everyday activities. According to Woods (1998), that activities should not be planned and that critical experiences are not always structured must be understood. Activities can be provided at unexpected times in different scenarios. Learning experiences will be the input in which people can identify that learning arises naturally from daily activities and can be articulated in school.

The last problem is the lack of human, educational, technological, and facility resources. For this reason, valuing the territory as a source of resources and natural scenarios to be used in the development of several learning experiences is essential. For Lozano (2019), rural inhabitants must connect their daily lives, the practices of the countryside, and the elements and products of the territory, so as not to replace them with others from the so-called world of development.

In this way there is clarity regarding the issues in La Eureka that allows following up with “Communitization in Cycle II” with community experiences as an axis.

Bio-learning from Community Experiences

The development of community experiences is based on three learning experiences: «Eureka canta y baila», «Sabores de mi tierra» and «Frutos de mi región», based on the process of production, harvesting, and marketing of coffee as the main economic product in this rural territory. The development of these experiences allowed articulating the school knowledge and the knowledge owned by the people of the community (Salcedo, 2021). All actions agreed and community-validated by the participants.

Based on data analysis, different categories and sub-categories are identified, and communitization becomes a critical element. The relationship between bio-community learning experiences, meetings from the main product of the region, and coffee allowed linking school knowledge with the learner’s peasant life (Romero, 2012; Gómez, 2015; Llambi & Pérez, 2007).

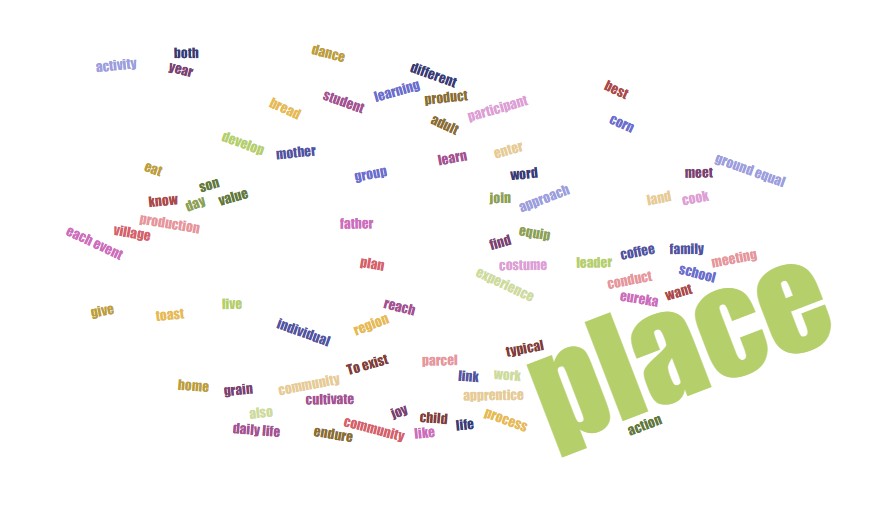

From an inductive approach, and from the open codification, 30 codes refer to: experience, aprendiencia (learning), community, learn, coffee, develop, communal, student, activity, eat, product, person, family, learner, meeting, work, process, know, child, leader, corn, school, participant, group, father, encounter, meet, get to know, home, region and action. As shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Communitization Open Code

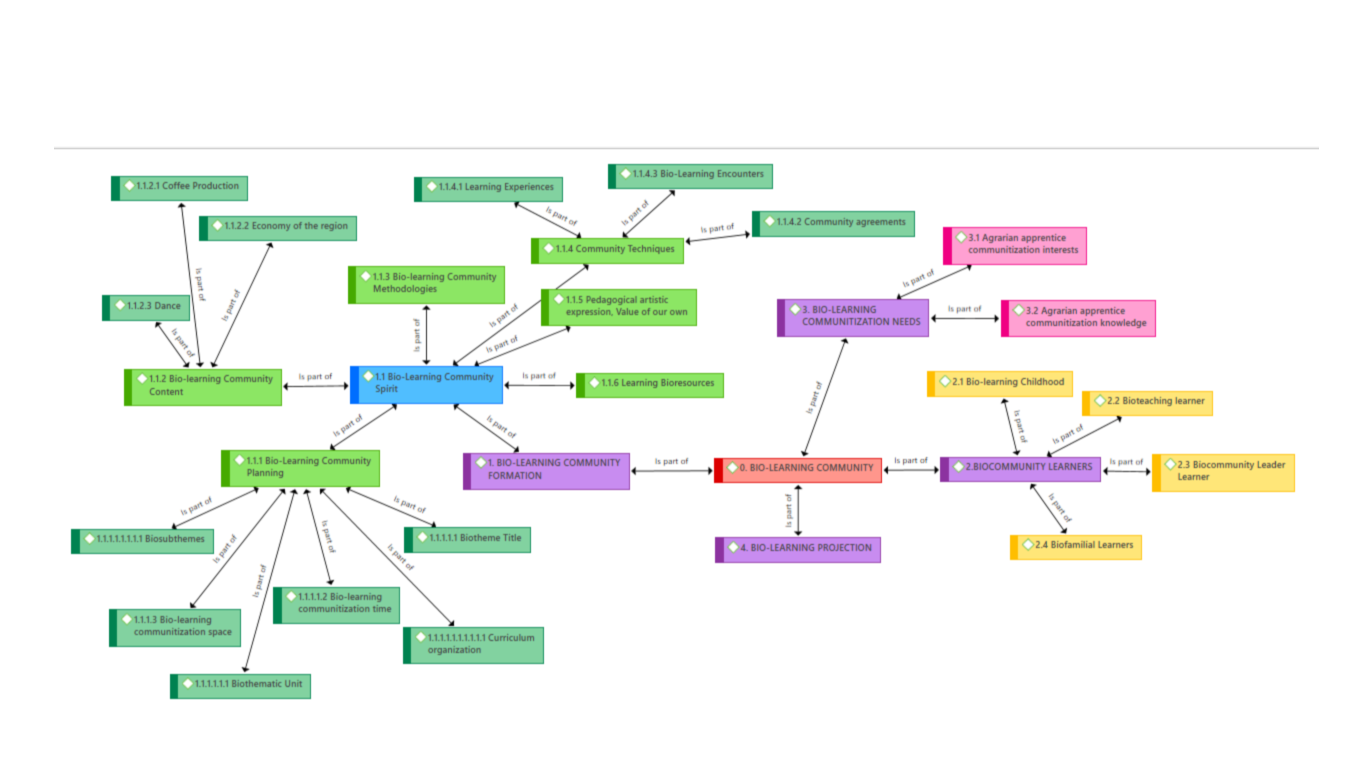

From this open codification a natural semantic network of communitization is generated. It establishes relationships, identity conjunction or axial codification between the "Bio-learning Community" macro category and the "Bio-learning Community Training", "Bio-community Learners", "Needs of Collaborative Bio-learners", and "Projection of Bio-learning Learning" categories. From those there is a triangulation and theoretical adjustment based on the researcher viewpoint.

Figure 5.Communitization Semantic Network.

As a first finding, the natural semantic network of communitization from axial codification allows identifying that the community processes related to the construction of rural knowledge, connected to school knowledge, are distinguished by a type of community called “bio-learning”. That school and community are articulated through community meeting can be inferred. The community is formed by processes of community bio-learning training, a vital training in, from, and for life.

This kind of training focused on the indigenous in the culture is based on participatory intelligence and shared from the territory. It is filled with community knowledge based on agriculture where there is constant learning and farmers can teach. In other words, the individuals are the basis of unity between community and community spirit in bio-learning.

All of this relates to traditions from generation to generation and are applicable through community learning experiences.

One way to put into practice what has been learned would be to enable learners to improve the production techniques of coffee, among peers and to improve product quality, sharing knowledge through life experience. (Observation No. 2. Frutos de mi Región, 2022, own translation)

The community spirit of bio-learning in this research presents a structural organization similar to the school curriculum by the active participation of the researcher, and at the same time, the teacher. In order to make the community bio-learning training feasible, a community plan is created organized as follows: title of the biotopics, biotopic unit, biosubtopics and curriculum organization of biotopics, i.e. a community-accepted and participative accepted bio-curricular structure. They develop in a time and space of bio-learning communitization vital to the plan. As this passage states:

The action group considered a structure based on questions that would allow them to reflect on the problem, and at the same time, develop a coherent and organized process, followed by the plan for the first event by the action group and approval for implementation by the participating learning community. (Observation No. 2. Frutos de mi Región, 2022, own translation)

Another category of the spirit of the bio-learning community is the content of bio-learning or vital community knowledge, such as coffee production, the economy of the region, and dance. Equally important is the category of bio-learning community methodologies, as ways to share learning based on learning experiences (Assmann, 2002). Each of these experiences has its own planning for building learning.

These learning experiences, as community learning techniques, emerged from community agreements and shared ideas to address the needs of bio-learning communitization. They also provide importance to artistic expression, pedagogical, and the value of learning from the territory, everyday life and the reality of life. Finally, with regard to the spirit of bio-learning community, the category of bio-resources emerges regarding human, physical, technological and didactic resources.

The bio-learning community comprised of “bio-learned children”, “bio- teaching learners”, “leading bio-community learners” and “bio-families” generates a community fabric between peasant knowledge and schoolchildren, as well as lifelong learning processes, because life learns and teaches (Salcedo, 2021).

An example of participation of various stakeholders involved in the community processes is shown in the following paragraph:

The achievement of the costumes and the stage elements was a community project, by acquiring the resources through activities managed by them. For this, all contributed with their artistic skills: the fashionist who made the costumes; the parents who collaborated with the achievement or doing other elements such as baskets, small bullets, among others. (Observation No. 1. «Eureka Canta y Baila, 2022», own translation)

This is intended to contribute to the territory by addressing the needs of bio-learning community, to consider the interests of an agricultural learning community and knowledge of an agribusiness community. So, the pedagogical requirement for the school is based on community dialogue, a dialogue that does not exclude the knowledge of people of the region. Lastly, the category “projection of the apprentice bio-learner” refers to what inspires the community on the community training that is intended to be maintained over time.

Discussion

Based on the findings, in Cycle I, “Problematization”, the category of rural territory was established. It contains rural, rurality, and new rural areas, and is associated with the categories of study: community experiences, bio-learning and school. The latter is understood as the scenario impacted by the other categories.

A school was observed, understood from reality, with still many traditionalist elements and scarce resources, but, at the same time, for participants as a dream school, in which they would like to learn through affection, the context, their realities and daily experiences, through their tastes that enable bringing together school and community knowledge. To achieve this goal, learning experiences linked community participants.

The main problem discovered by community participants is the disconnect between school and community, and the lack of relationship between school knowledge and community knowledge. It is generated by the rupture among ideas, beliefs, and customs between adults and children. There is a total disconnect between children's beliefs and the realities they live with their families in their homes. There is no connection with what is taught and learned in school. Intergenerational practices have been lost and there have been problems with human, educational, technological, and infrastructure resources.

Then, in Cycle II, “Communitization”, community experiences are developed, based on learning experiences regarding the processes of coffee production, harvesting and marketing. From open coding, a natural semantic network of communitization is generated by establishing relationships, identity conjunction or central coding to a macro-category (bio-learning community). The emerging network of communitization allows identifying that the community processes related to the construction of peasant knowledge and the school knowledge are distinguished by a type of community called bio-learner from the same bio-learning, or learning in, from, and for life.

The contribution of community members to the context is significant, as it mobilized different actors to turn to the school, rethink, and commit themselves to building it together as co-builders of other learnings. That is, contrary to the simplistic equation in crisis when Assmann (2022) explains that knowledge arises through learning. And how does learning arise? Through teaching. From this approach, a good learning would be the normal result of good teaching and disciplined study. From a different perspective, school keeps the imagination alive, recreates the social structure and produces the way man thinks and acts, or reproduces inspiration. In contrast, school fosters innovation and the mobilization of old structures for transformation.

Community experiences approach rural knowledge through the school, its dynamics, its everyday life, through the analysis and reflections in relation to the communitization of school practices and knowledge, bio-learning and the rural territory that emerges in the relationship between school and community. According to Torres (2013), a community is made up of social forms that share values, interests, and goals. Generally, this is associated with a small area or small population, often poor or marginalized that shares a type of property (ideals, needs, goals). This is a unified and important image of society that makes it impossible to see the differences, the conflicts of any organization. From the concept of rural school as a place based on the social co-construction of knowledge, it starts by observing some activities of the rural population that can be within a good educational and cultural environment as a response or resistance to levels of current political and social inequality.

Providing information on rural education is also important. Thinking about rural education and its important role in the educational system itself seems appropriate, to understand it openly according to its approval modified by real life events of the community. Rural education responds to the damage from the health level in terms of its decontextualization and the significant disengagement of the urgent needs. Contreras and Pérez (2010) argue that learning about the experience and its ambiguity provides the opportunity to break with educational and social dichotomy to go beyond the concept of knowing and research. The study of the experience has the concepts of “meaning” and “knowing,” as support and research findings, guardians of the relations of ideas and experiences to show the complexity of each situation. Different views of rural education and its structure must be considered to create knowledge based on the way in which community relations are taught and defined in these rural areas.

Likewise, rural education uses social knowledge, from school practices, as a process of continuous learning, and introduces two new ideas in the proposal: bio-learning and the communitization of school methods and knowledge. This perspective allows for considering possible paths of other rural organizations that includes new knowledge. Knowledge of the situation, built by the real community and the school, can be a catalyst for change in certain rural educational environments. Parra et al. (2019), states that bio-learning implies the ability to think and agree from mutual respect, the approach others through their family and social contexts. This new way of looking at learning makes human deployment possible. Then, the creation of bio-learning communities aimed at bringing together groups and leaders in processes of organization and co-building is proposed. It contributes to the transformation, democracy, and the development of the educational problem from the institutional integration, managed as systems of life to overcome the current dominant traditional models.

Conclusions

The CPAR method is the base from which to demonstrate that the learning community is part of the research and the products of the present study. The method allowed identifying the main problem as the gap between the school and the rural community, a central axis for the approach of different cycles that generates learning experiences. Therefore, the research elements are not only in the spiral, but in the product of interaction, of the active community participation of all learners to reduce the distances between community members. This makes sense to these learning experiences as facilitators of bio-learning, bio-communitarianism, and bio-learner. They emerge from the activities of the countryside between rural children and families, and their relationships. Thus, it may be said that to enable bio-pedagogy, the community demands that the school be community-built, change its curricular, school, and disciplinary learnings.

In this process, the subject being trained to comprehend that every bio-learning action is biological and self-creative is crucial. This means that there is a metamorphosis of learning through bio-learning, from student to biological learner and family collaboration in their children's schoolwork, to be called a learning bio-community. That is to say, the subject continuously learns from what people do in the territory and the ability to be involved, bio-teaches with the rural teacher.

In short, the creation of learning experiences that enable bio-learning in students in La Eureka at Tarqui-Huila results in a direct challenge to teaching or an advocacy for constructivism, as well as fosters a community-based critical experience environment that facilitates the development of real-world sensibilities and acts as a catalyst for both curriculum-based and rural learning experiences.

This means applying practices to the educational setting and also planning strategies or experiences related to rural life. It also implies living the rural reality with the same students who have educated their sons and daughters under the same knowledge, maybe far from school; and also a rural school that has trained from the essential areas of established knowledge, forgetting their context and reality.

References

Assmann, H. (2002). Placer y ternura en la educación. Hacia una sociedad aprendiente. Ediciones Madrid.

Bolaños, J. (2021). Programas educativos dirigidos a poblaciones de los territorios rurales. experiencias en Argentina y México. Tendencias Pedagógicas, 37, 7-17. https://Dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=7701594

Bonilla, E. & Rodríguez, P. (2005). Más allá del dilema de los métodos. Norma.

Contreras, D. & Pérez, L. (2010). Investigar la experiencia educativa. Revista Mexicana de Investigación Educativa, 19(62), 885-892. https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=14031461011

Escobar, A. (2014). Sentipensar con la tierra: nuevas lecturas sobre desarrollo, territorio y diferencia. UNAULA.https://journals.openedition.org/amerika/7918

Funke O. & Ayob, S. (2020). The Utilisation of Translanguaging for Learning and Teaching in Multilingual Primary Classrooms. Multilingua, 41(1), 105-129. https://doi.org/10.1515/multi-2020-0072

Glaser, B. G. & Strauss, A. L. (1967) The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Aldine.

Gómez, E. (2015). Aspectos teóricos de las nuevas ruralidades latinoamericanas. Gazeta de Antropología, 31(1), 1-15.https://digibug.ugr.es/handle/10481/36669

Gonzáles, A.B., Cortés, G.P. & Leite, M.A. (2020). Las aulas multigrado en el medio rural en Andalucía. Visiones docentes. Revista de investigación educativa de la Rediech, 11(2), 25-38. https://doi.org/10.33010/ie_rie_rediech.v11i0.860

Gutiérrez, F. (2010). Las nuevas ciencias de la vida. Polis, Revista de la Universidad Bolivariana, 9(25), 223-233.https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/305/30512376012.pdf

Habermas, J. (1986). Ciencia y técnica como «ideología». Tecnos.

Kemmis, S., & McTaggart, R. (2013). La investigación – acción participativa. La acción comunicativa y la esfera pública. In: Yvonna, N., & Lincoln, Y. Estrategias de Investigación Cualitativa. Manual de Investigación Cualitativa. Volumen III. (pp.361-439). Gedisa.

Kemmis, S., McTaggart, R., & Nixon, R. (2014). The Action Research Planner. Doing critical Participatory Action Research. Springer. https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-981-4560-67-2

Llambí, L., & Pérez, E. (2007). Nuevas ruralidades y viejos campesinismos. Agenda para una nueva sociología rural latinoamericana. Cuadernos de Desarrollo Rural, 4(59), 37-61.https://biblat.unam.mx/hevila/Cuadernosdedesarrollorural/2007/no59/2.pdf

López, R. L. R. (2006). Ruralidad y educación rural. Referentes para un programa de educación rural en la Universidad Pedagógica Nacional. Revista colombiana de educación, 2(51) 138-159.https://revistas.pedagogica.edu.co/index.php/RCE/article/view/7687

Lozano, D. (2019). Calidad educativa y cumplimiento del derecho a la educación de la población rural colombiana. Revista de la Universidad de La Salle, (79), 41-66. https://doi.org/10.19052/ruls.vol1.iss79.3

Mate, D., Dos Santos, K., & Fornari, K. (2022). Práticas comunitárias e currículo educação do campo, das águas e florestas na Região Norte e Nordeste. Revista e-Curriculum, 20(1), 279-301.https://revistas.pucsp.br/index.php/curriculum/article/view/54892

Novoa, P. A & Camacho, S. C. (2017). Innovación y Comunitarización en la educación. Revista de la Universidad La Salle, 73(3) 13-31.https://ciencia.lasalle.edu.co/ruls/vol2017/iss73/1/

Ocaña, A. & Reyes-López, M.L. (2019).'My Favorite Song': Understanding a Music Learning Ecology of Children From Interaction Among Media, Family and School Contexts. British Journal of Music Education, 36(3), 113-123.https://doi.org/10.1017/S0265051719000081

Parra, L., Chaverra, L. & Castro, A. (2019). El bioaprendizaje: posibilidad para desplegar la condición de humanidad en los escenarios educativos. Intersticios: Revista sociológica de pensamiento crítico, 13(1), 191-199.https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=6885082

Pérez, E., & Cárdenas, E. (2020). De la educación rural a la educación rural comunitaria: reflexiones desde el municipio de San Jerónimo Coatlán, Oaxaca. Revista Latinoamericana de Estudios Educativos, 1(1), 225-250.

Romero, J. (2012). Lo rural y la ruralidad en américa Latina: Categorías conceptuales en Debate. Psicoperspectivas, 11(1), 8-31.https://scielo.conicyt.cl/pdf/psicop/v11n1/art02.pdf

Salcedo, C. J. R. (2021). Educación y Afectos. Etnografía Afectiva para Reconocer la Subjetividad Campesina de la Vereda la Manga en Yopal (Casanare).Etnografía Afectiva para Reconocer la Subjetividad Campesina de la Vereda la Manga en Yopal (Casanare). Ediciones Unisalle.

Takeuchi, M. A., Sengupta, P., Shanahan, M.C., Adams, J. D. & Hachem, M. (2020). Transdisciplinarity in STEM Education: A Critical Review. Studies in Science Education, 56(2), 213-253. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057267.2020.1755802

Torres, A. (2013). El retorno a la comunidad: problemas, debates y desafíos de vivir juntos. CINDE y EL BÚHO.

Vera, A. N.Y. (2019). Escuela rural y territorio: una construcción para la paz. Revista Latinoamericana De Estudios Educativos, 49(1), 293-314.https://rlee.ibero.mx/index.php/rlee/article/view/41

Woods, P. (1997). Experiencias críticas en la enseñanza y el aprendizaje (Translation by J. Bayo). Paidós.

Woods, P. (1998). Experiencias críticas en la enseñanza y el aprendizaje. Ediciones Paidós.