Exploring the Differential Impact of Gender in the Contexts of Incarceration in Argentina1

La diversidad en la adversidad: explorando el impacto diferencial de género en los contextos de encierro en Argentina

Diversidade na adversidade: explorando o impacto diferencial do gênero em contextos de confinamento na Argentina

Received 04/05/2023

Accepted on 07/26/2023

|

How to cite Safranoff, A. & Tiravassi, A. (2024). Diversity in Adversity: Exploring the Differential Impact of Gender in the Contexts of Incarceration in Argentina. Ánfora, 31(57), 66-94. https://doi.org/10.30854/anf.v31.n57.2024.1080 |

Ana Safranoff2 http://orcid.org/0000-0002-0407-0650 Argentina Antonella Tiravassi3 https://orcid.org/0009-0002-3153-2918 Argentina

|

Abstract

Objective: This study seeks to explore, describe, and quantify the effects that the experiences of incarceration have on women in prison contexts in Argentina. Methodology: The results of an original database were analyzed. The database includes two surveys conducted by the Center for Latin American Studies on Insecurity and Violence (CELIV/UNTREF) in 2013 and 2019 in prisons of the Federal and Buenos Aires Penitentiary System. The sample consisted of 845 males and 188 females who participated in the survey in 2013, and 838 males and 200 females in 2019. Results: The results of this study indicate that there are gender differences in the effects of incarceration on the inside, which are mainly crystallized in the behavior of the nearby containment networks. For women, contact with their emotional environment is more limited than for men.

Keywords: impact; gender perspective; prison; surveys; Argentina (obtained from SAIJ thesaurus).

Resumen

Objetivo: en el presente estudio se busca explorar, describir y cuantificar los efectos que las experiencias del encierro manifiestan en las mujeres al interior de los contextos penitenciarios en Argentina. Metodología: para ello, se analizan los resultados de una base de datos original, que incluye dos encuestas realizadas por el Centro de Estudios Latinoamericanos sobre Inseguridad y Violencia (CELIV/UNTREF) en el año 2013 y en 2019 en cárceles del Sistema Penitenciario Federal y Bonaerense. La muestra consistió en 845 varones y 188 mujeres que participaron de la encuesta en el 2013, y 838 varones y 200 mujeres en el año 2019. Resultados: los resultados de este estudio permiten indicar que existen diferencias de género en los efectos del encierro en el adentro, que se cristalizan principalmente en el comportamiento de las redes de contención cercanas. Para las mujeres, el contacto con su entorno afectivo se ve más limitado que para los varones.

Palabras clave: impacto; perspectiva de género; prisión; encuestas;

Argentina (obtenidos del tesauro SAIJ).

Resumo

Objetivo: este estudo busca explorar, descrever e quantificar os efeitos que as experiências de encarceramento têm sobre as mulheres em contextos prisionais na Argentina. Metodologia: para isso, foram analisados os resultados de um banco de dados original, que inclui duas pesquisas realizadas pelo Centro de Estudos Latino-Americanos sobre Insegurança e Violência (CELIV/UNTREF) em 2013 e 2019 em prisões do Sistema Penitenciário Federal e de Buenos Aires. A amostra consistiu em 845 homens e 188 mulheres que participaram da pesquisa em 2013, e 838 homens e 200 mulheres em 2019. Resultados: os resultados deste estudo indicam que existem diferenças de gênero nos efeitos do confinamento interno, que se manifestam principalmente no comportamento das redes de apoio próximas a eles. Para as mulheres, o contato com seu ambiente afetivo é mais limitado do que para os homens.

Palavras chaves:

impacto; perspetiva de género;

prisão; pesquisas; Argentina (obtidas do tesauro SAIJ).

Introduction

The female incarceration rate has shown spikes in recent years, and many studies highlight that this rate is growing much faster than the female crime rate (Morris, 1987; Seear & Player, 1986; Davis, 1996; Gelsthorpe & Morris, 2002). Women are overrepresented in property, non-violent, and drug trafficking-related crimes. This "criminal paradox", as Gelsthorpe and Morris (2002) call it, reflects the need to force a radical change, and for this it becomes fundamental to rethink punitive policies (Almeda, 2017) and the implications that imprisonment assumes from a gender approach.

Different works (CELS et al., 2011; Monclus, 2017) reveal that female incarceration has a different impact on the outside than male incarceration, and this is especially linked to the gender roles socially assigned and played by one and the other. The imprisonment of women transcends their individuality and also affects their environment, especially the people who depend on their care. Considering the central role assumed by women in the daily care and economic support of their children and other dependents, imprisonment provokes a strong emotional void and impact on them, especially on their children, as the daily bond is interrupted and major changes are brought about in the modes of subsistence, organization, and family dynamics. As Monclus (2017) puts it, "the imprisonment of these women entails an increase in the vulnerability of their households, if not their dismemberment and the helplessness of the minors" (p. 376). These elements lead to questioning the rationality of the current criminal policy related to women, and lead to consider that there is a disproportion between the penalties they suffer and the damage caused by the crimes attributed to them (CELS et al., 2011).

However, female imprisonment is not only felt differentially outside, but also within the context of confinement itself. This study seeks to explore, describe, and quantify the effects that the experiences of incarceration have on women in prison contexts. For this purpose, we analyze the results of an original database that includes two surveys conducted by the Center for Latin American Studies on Insecurity and Violence (CELIV/UNTREF), in 2013 and 2019, in prisons of the Federal and Buenos Aires Penitentiary System of Argentina. The sample consisted of 845 males and 188 females who participated in the survey in 2013, and 838 males and 200 females in 2019. This data collection format made it possible to recover the voices of the persons deprived of liberty, and getting closer to the reality of the contexts of incarceration possible. In addition, the studies was carried out in two different time periods, which allows for reading in a comparative and evolutionary key.

In this opportunity, only some factors that illustrate the differential impact will be analyzed, without pretending to exhaust the subject, but rather to contribute to broadening the evidence and knowledge on the subject. Here various dimensions (ties of containment/articulations) and health-wellbeing that intersect with others, such as those linked to the life trajectories with which they arrive at incarceration, and which are understood as factors of exclusion are analyzed. The following are the different dimensions investigated in this article: frequency of visits, access to conjugal visits, types of supplies acquired from visits, depression as a psycho-emotional illness perceived as a result of incarceration, having children and a partner, employment status before detention and the situation of violence perpetrated by their partners.

This article is conceptualized within a theoretical framework that understands gender as a social construction. It is a dynamic concept or non-stable category (Butler, 1990) that makes providing visibility to the inequalities that organize society possible and is the result of historical processes that perpetuate inequities in all spheres of life. These social constructs are susceptible to analysis, debate and, eventually, transformation. Gender inequalities refer to the conditions of hierarchical imbalance and privileges that in society are granted to men and their capacity to exercise power, to the detriment of women and the LGBTI+ population. This is a systemic situation that is reproduced and expressed in a multiplicity of inequalities that place obstacles regarding the access to fundamental rights for women and the LGBTI+4 population.

Methodological Considerations

This article is based on primary data produced from the Survey of Individuals Deprived of Liberty conducted by the Center for Latin American Studies on Insecurity and Violence (CELIV), with support from UNDP and IDB in prisons in eight Latin American countries (Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Honduras, Mexico, and Peru) and in six Caribbean countries (Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago, Guyana, Bahamas, Barbados, and Suriname), between 2013 and 2019.

The survey was developed by a team of researchers from CELIV ⸺belonging to the Universidad Nacional de Tres de Febrero (UNTREF, Argentina)⸺ based on similar instruments conducted by researchers from CIDE (Mexico), and inspired by the surveys conducted approximately every six years in the U.S. by the Bureau of Justice Statistics. The collection tool, which was adapted to the reality of each country by introducing specific questions, consists of approximately 270 closed questions and 460 variables. It was tested in several pilot tests, and technical adjustments have been made considering the specificities of the language commonly used in each of the countries. However, 90% of the questions are common to all cases, resulting in a basis for comparison at the regional level.

This article analyzes only the case of Argentina, which has one of the most recent data sets (2019) and is the only one that allows for temporal comparison (2013-2019), as two surveys have been conducted in different time periods. Both surveys were applied to a representative sample of individuals deprived of their liberty in Argentine prisons from the federal and Buenos Aires systems. The samples are random, representative, and stratified by gender (hence quotas were developed accordingly). Female prisoners, being proportionally fewer, have been overrepresented in the sample in order to achieve a sufficient sample size of this group for subsequent statistical tests. In 2019, a total of 1,038 individuals were interviewed (838 males and 200 females), five more compared to 2013, where the sample consisted of 1,033 cases (845 males and 188 females).

For this paper, descriptive analysis techniques (frequencies and contingency tables) were used to explore gender differences in the effects of confinement. Most of the results are set out graphically (bar charts) and presented in comparative terms; based on gender (male and female) and the year the survey was conducted (2013 and 2019).

General and Prevalent Characteristics of Women and Men in the Context of Incarceration in Argentina

Incarcerated men and women in Argentina differ in terms of the crimes for which they are in conflict with the law. The most frequent reason for which women are imprisoned is linked to drug trafficking and/or possession (49.4% of the cases). On the contrary, men are mostly detained for robbery (43.2%). Likewise, women are involved in less violent types of crime than men. In the first place, they are mostly related to unarmed crimes: 41% of the men indicate that they were carrying a weapon during the criminal act for which they were punished; this percentage is reduced to 24.9% in the case of women. Second, females participate ⸺to a greater extent than males⸺ in crimes where other people were present; that is, they were not alone (67.4% females vs. 59.1% male). These results highlight the importance of dependency bonds in the development of female criminal behavior (Azaola, 2005; Mullins & Wright, 2003; Yagüe, 2007).

Table 1. General Characteristics of Incarcerated Women and Men in Argentina.

|

Argentina - 2019 |

Males |

Females |

|

Theft |

43.2% |

25.0% |

|

Homicide |

14.3% |

8.3% |

|

Drug trafficking/possession |

16.7% |

49.4% |

|

Sexual offenses |

11.1% |

1.2% |

|

Other crimes |

14.8% |

16.1% |

|

Carrying some kind of weapon |

41.0% |

24.9% |

|

There were more participants in the crime |

59.1% |

67.4% |

|

In prison for a prior felony |

39.4% |

21.7% |

|

Have you ever in your life held a gun in your hand? |

70.3% |

40.5% |

|

In a juvenile center |

18.5% |

13.8% |

|

Median current age of arrest |

30 |

34 |

Source: Prepared by the authors based on the Survey of Individuals Deprived of Liberty (CELIV/UNTREF).

Women are linked to less violent crimes, and to a shorter history of conflict with the law than men. They are less likely to be repeat offenders (21.7% have been previously incarcerated for another offense, while in males this percentage rises to 39.4%). A smaller proportion of women were in juvenile detention centers (13.8% of females compared to 18.5% of males). Women have had less contact with weapons (40.5% of females have ever had a weapon in their hands compared to 70.3% of males). Furthermore, the data reveal that women have been arrested at a later age than men.

Differential Impact Based on Evidence from the Data

Imprisonment assumes a differential meaning for women and men: for women, prison is doubly stigmatizing and painful if one takes into account the role that society has assigned to them. A woman who goes through prison is qualified as "bad" because she contravened the role that the imagery confers on her as wife and mother, in terms of her submission, dependence and docility (Antony, 2007). Women who find themselves in conflict with the criminal law obtain greater social scorn than men, since they departed from the prevailing mandate (CELS et al., 2011). The weight of the blame associated with delinquency and social rejection for not having followed the expected gender roles falls on them (Carrillo et al., 2020). Women are not only judged for the crime committed, but also for having violated pre-established gender roles.

The following sections, based on the data, explore, describe, and quantify some of these incarceration experiences for males and females.

Incarcerated Women Suffer Greater Isolation from their Social Environments

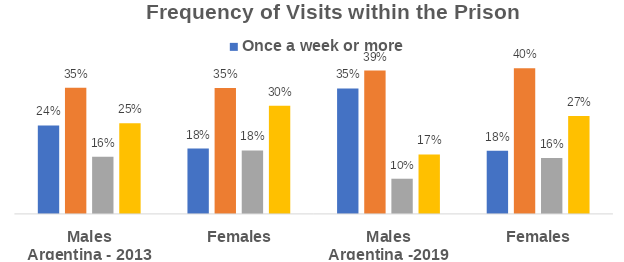

The so-called "visit" to persons deprived of liberty, apart from being a right, is a fundamental element that contributes to the rehabilitation and social reintegration process (Reyes & Quispe, 2017). The data obtained from the two surveys (2013 and 2019) evidences that males receive visits with a weekly frequency in a higher proportion than females. In 2019, 18% of females received visits "once a week or more," while in males that percentage increases to 35%. Also noteworthy is that 27% of women "never" receive visits, which happens to a lesser extent among men (17%).

Figure 1. Frequency of Visits within the Prison.

Source: prepared by the authors based on the Survey of Individuals Deprived of Liberty (CELIV/UNTREF, 2013 and 2019).

There is also an outstanding gender divergence regarding conjugal visits. In 2019, in Argentina, 61% of men and 41% of women accessed this modality of contact with the outside. The right to conjugal visitation applies to both men and women, but:

Priority has always been given to the man's "need" to exercise his right to enjoy conjugal visits, and the woman have been displaced [...] it is assumed that women, from the outset, do not want or deserve conjugal visits. (Reyes & Quispe, 2017, p. 222, own translation.)

Figure 2. Persons in Contexts of Confinement Who Received conjugal Visits According to Gender and Year of the Survey.

Source: prepared by the authors based on the Survey of Individuals Deprived of Liberty (CELIV/UNTREF, 2013 and 2019).

The difficulties faced by women in detention in accessing the right to conjugal visits have been highlighted by different authors (Rodriguez, 2003; Antony, 2003). The literature generally indicates that women are subject to more stringent requirements than men in prison, such as proof of partnership, medical examinations and adoption of a family planning method. While men are allowed to define with a wide margin of freedom who is the person who will attend on the days and at the times designated for conjugal visits, women detainees are subject to conditions and obstacles that limit their right to this type of visit (Romero et al., 2014). Although the source explored in this study lacks sufficient data to determine or affirm the causes of the lower access, or to validate that they are linked to restrictions imposed by the institution itself, it does reveal a marked gender difference; at least in terms of the scope of this right.

The information related to family and conjugal visits shows that women in prison in Argentina suffer greater isolation in terms of contact with their families and relatives; many of them do not receive visits or receive them more sporadically than men. A comparative reading of the evidence in a temporal key (2013-2019) does not allow for observing progress, but rather shows a situation that remains constant over time.

Exploring the reasons for this increased isolation of incarcerated women in Argentina in greater depth is a pending challenge. CELS et al. (2011) draw attention to a specific form of institutional violence against women, which consists of hindering their links with the outside world. From this point of view, the isolation of women would be enhanced due to the specific barriers and difficulties imposed by the institution itself when it comes to receiving visits. In the same vein, it should be noted that, while there are few prison units that house women, the contexts of confinement tend to be, on average, farther away from their homes of origin, which has a direct impact on the possibilities of having visitors (Matthews, 2003).

The latter calls for reflection on public policies and among decision-makers in the different levels of the penal system. The location of prisons and the arbitrary nature of transfers are issues that make it impossible for a large majority of women deprived of their liberty to serve their sentences close to their homes and, consequently, to their affective environments (CELS et al., 2011).

However, in addition to institutional obstacles, mentioning the greater abandonment suffered by women from their own environment is necessary (Galván et al., 2006). Studies carried out in confinement contexts in different countries confirm that women, to a greater extent than men, suffer abandonment by the people most significant to them (Lagarde, 1993; Azaola, 1996; Azaola & Yacamán, 1996; Muraskin, 2000). In this sense, specialists have affirmed that the sentimental partners (spouses or cohabitating partners) give up ties more when it comes to women deprived of liberty than men (Pinto, 1999; Galván et al., 2006). This is evidence of the marked gender role culturally assigned to women in relation to the accompaniment, care, and support of the incarcerated person. When a family member is incarcerated, it is almost always women who play an active role in maintaining the bond (CELS et al., 2011).

There is a vast literature that considers that the abandonment of the affective environment is due to social rejection, a product of the stigma that falls on women in prison for failing to comply with culturally expected gender roles. The reclusion of women is socially perceived as proof of a transgression of social and moral values, so that in the eyes of the social context they are not worthy of support and consideration, but of rejection and exclusion (Azaola, 1996; Galván et al., 2006). In this sense, for example, of note is that women do not usually express shame when accepting that their partners are in prison, while men do not even mention it (Reyes & Quispe, 2017). Being in conflict with the law is, socially, more reproached among women than among men; and it is possible that this is what is associated with the lower social support received by women in contexts of confinement (Sardinha, 2015).

In summary, although tracing the causes and origins that could explain the lower level of support for women in the data analyzed for the purposes of this study is not possible, distinguishing issues that derive from this situation is possible. In Argentina, the fact that women in the context of confinement are more isolated from their environment could be because their own emotional ties abandon them or because they suffer from institutional barriers (greater difficulties in accessing certain rights). Be that as it may, this scenario places them at a disadvantage. On the one hand, it hinders the possibility of accessing the goods that individuals deprived of liberty can only obtain through the support of their family/affective networks. On the other hand, this limitation entails significant emotional damage.

The support of family and friends during incarceration can make a huge difference in the living conditions of women in prison, as it is key to the well-being of the person deprived of liberty (Galván et al., 2006). It has been shown that support and social networks help human beings to find themselves in states of relative well-being, and to overcome stressful events they face during their lives. Social support is defined as "the bonds among individuals or between individuals and groups that serve to enhance adaptation when one faces situations of stress, challenge or deprivation" (Caplan & Killilea cited by Aranda & Pando, 2013 p. 234, own translation). In this framework, social support is presented as a valuable resource during incarceration, which, as shown above, women rely on to a lesser extent than men.

Incarcerated Women and Men: Differential Support from the Environment

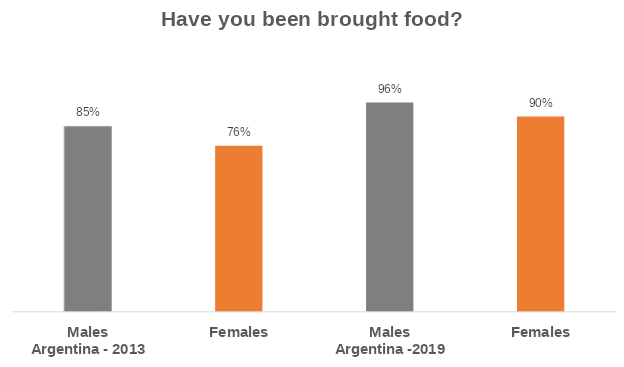

The data reveal that the frequency of visits is different between men and women in confinement contexts, and the type of support they receive in each context is different as well. While men report, in a slightly higher proportion, that visitors provide them with food, women indicate that they provide them with money.

Figure 3. Persons in Context of Confinement to Whom Food Has Been Brought According to Gender and Year of Survey.

Source: prepared by the authors based on the Survey of Individuals Deprived of Liberty (CELIV/UNTREF, 2013 and 2019).

The fact that males receive more food could be linked to traditionally assigned gender roles, where women, who are the ones who visit them, have historically been responsible for daily food; both in terms of food acquisition and food processing (Del Campo & Navarro, 2012). As indicated by studies on this subject, CELS et al. (2011) “in the line of visitors in male prisons we find a greater number of women ⸺spouses or partners, mothers, sisters⸺ and in the line of visitors in female prisons [...] we also find women ⸻mothers, sisters, etc.⸻” (p. 91, own translation).

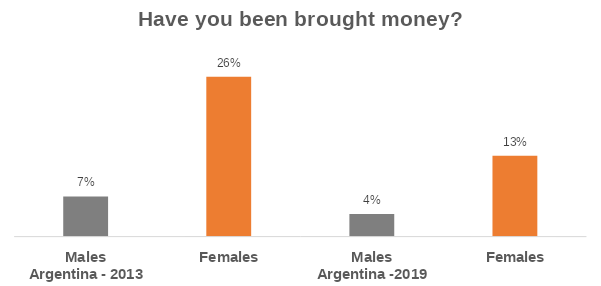

Nevertheless, there is a need to explore more fully the reasons why women receive more economic support. This requires special attention, mainly in a context of greater isolation from their social environment; that is, they visit them less, but when they do, they give them money. It is possible that this is linked to institution-specific issues (such as the possible need to purchase certain goods in women's prisons), but in any case, the data suggest that women receive more material support (money) and less emotional support (the visit itself).

Figure 4. Persons in Context of Confinement to Whom Money Has Been Brought According to Gender and Year of survey.

Source: prepared by the authors based on the Survey of Individuals Deprived of Liberty (CELIV/UNTREF, 2013 and 2019).

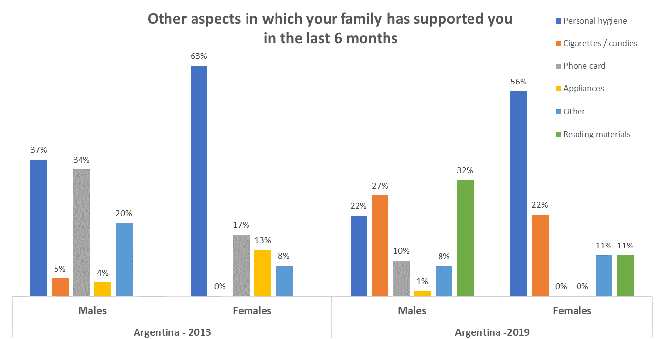

There are differences between men and women in relation to other aspects in which they receive support from their families. Women are widely noted for receiving products for their personal hygiene. In 2019, more than half of women (56%) indicate that, in the last six months, their family has supported them with products such as deodorant, toothpaste, toothbrush, etc. On the other hand, support for men is distributed among reading material (32%), cigarettes/smokes (27%) and personal hygiene (22%).

Figure 5. Persons in Contexts of Confinement Who Received Other Types of Support According to Gender and Year of the Survey.

Source: prepared by the authors based on the Survey of individuals deprived of liberty (CELIV/UNTREF, 2013 and 2019).

Women Get Sicker Inside Prison

The data analyzed reveal that women have less social support and experience greater isolation from family and friends. This situation, together with the concern for their children and the loss of the daily exercise of care are some of the causes that lead to a high incidence of psychological problems, situations of self-harm and anxiety crises among women detainees (CELS et al., 2011). In this sense, a 2006 report by the National Institute of Women of Mexico and UNDP indicates that, for women in the context of confinement, "the frustration, guilt, and impotence of not being able to be with their sons and daughters and give them 'the best' constitute another punishment, a double captivity" (p. 62).

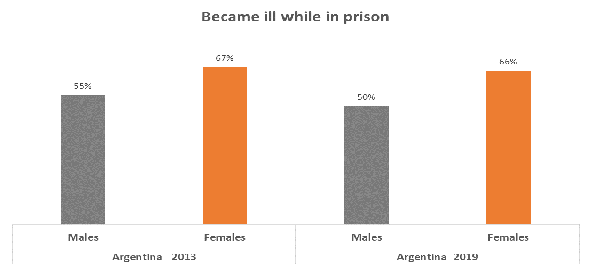

Empirical evidence reflects that confinement has a greater impact on women's physical and emotional well-being. Analysis shows that females contract illnesses in higher proportion than males inside prison; in 2019, 66% report having fallen ill, while this percentage drops to 50% for males.

Figure 6. Persons Who Became Ill while in Prison by Gender and Survey Year.

Source: prepared by the authors based on the Survey of Individuals Deprived of Liberty (CELIV/UNTREF, 2013 and 2019).

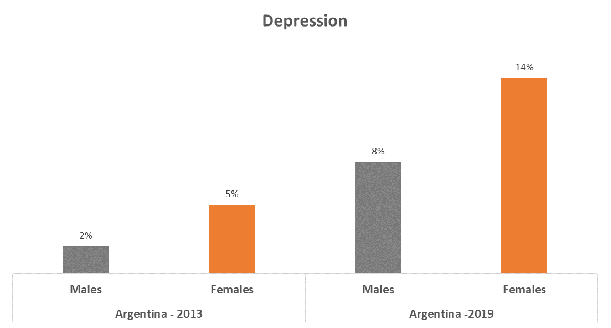

Likewise, analysis shows that women indicate suffering from depression. This is consistent with previous studies that have indicated that the experience of incarceration has a greater impact on the deterioration of women's mental health and/or psychoemotional state (Antony, 2003; Cárdenas, 2011; Calvo, 2014).

The literature argues that people with mental illness in the context of confinement do not have adequate treatment, beyond the possible confinement in a secluded ward and the exaggerated provision of medication (Lombardo et al., 2016; Alfonsín, 2015). In this sense, another gender-related health care consideration is the abuse of psychotropic drugs for tranquilizing and disciplining purposes that are overprescribed to women (Antony, 2003; Cárdenas, 2011; Calvo, 2014). Vigna's study (2012) in Uruguay shows that the proportion of women taking regular medication is almost double that of men, while the percentage of women taking psychotropic drugs is almost three times higher than that of men. The control exercised by pharmacological means occurs to a greater extent in female prisons than in male prisons (Vigna, 2011). Even, Alfonsín's (2015) study in the Ezeiza prison of the Federal Penitentiary Service of Argentina demonstrates how the temporary transfer to the Psychiatric Annex is presented for women as a practice of covert sanction, shielded within the medical-psychiatric discourse.

Figure 7. Incarcerated Persons Suffering from Depression According to Gender and Year of the Survey.

Source: prepared by the authors based on the Survey of Individuals Deprived of Liberty (CELIV/UNTREF, 2013 and 2019).

The Exclusion of Exclusion

Finally, although prison particularly excludes and isolates women deprived of liberty, women were already socially excluded before being convicted (CELS, 2011) is a necessary consideration to be made. In this sense, there are those who allude to the "exclusion of exclusion" (Almeda, 2017). The female population in contexts of confinement is a minority with a history of multiple social exclusions that are exacerbated during their stay in prison (Carrillo et al., 2020).

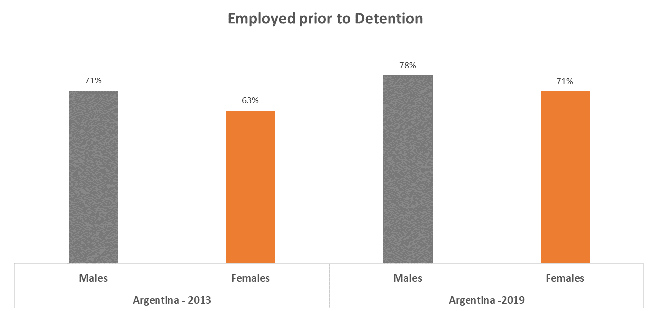

The situation of women, prior to arrest, shows a wide range of vulnerability in relation to men, both in terms of their families and work situations. Data shows that women have a slightly higher level of unemployment than men in the month prior to their arrest.

Figure 8. Incarcerated Persons Who Were Employed prior to Detention According to Gender and Year of the Survey.

Source: prepared by the authors based on the Survey of Individuals Deprived of Liberty (CELIV/UNTREF, 2013 and 2019).

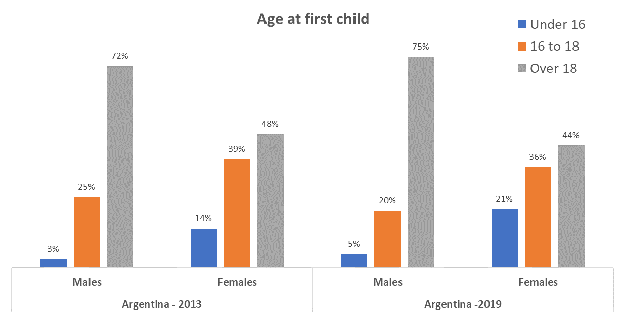

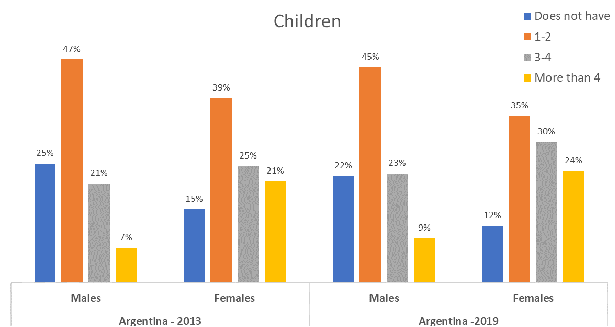

Additionally, incarcerated women are ⸻in a higher proportion than men⸻ adolescent mothers, without a partner and/or with a greater number of children. At the same time, in 2019, 75% of males deprived of liberty had their child when they were over 18 years old; this percentage is reduced to 44% among females. Twenty-one percent of women had their first child under the age of 16 and 36% between the ages of 16 and 18; these percentages are reduced to 5% and 20% respectively among men. A time-slice reading (2013-2019) allows for observing that there is no major progress in this line, but that, on the contrary, a slight increase is observed in regard to early pregnancy among women.

Figure 9. Age at which Incarcerated Persons Had Their First Child According to Gender and Year of the Survey.

Source: prepared by the authors based on the Survey of Individuals Deprived of Liberty (CELIV/UNTREF, 2013 and 2019).

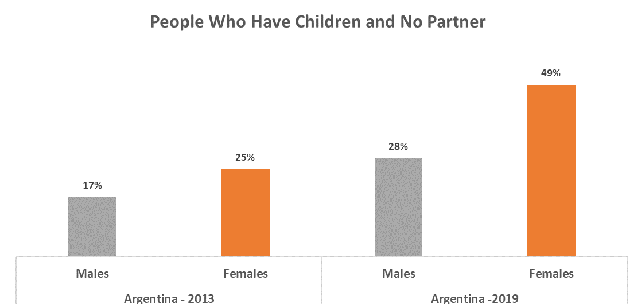

Likewise, 49% of women who have children do not have a partner. Although these data do not allow for asserting that not being in a couple means that the responsibility for caregiving falls exclusively on them. This can possibly be inferred. Several studies conducted in other contexts of confinement highlight the high number of women in prison who are heads of single-parent families, and who are responsible for the children and for sustaining the family unit (Bloom et al., 1994; Owen & Bloom, 1995; Antony, 2007; Ruidíaz, 2011; Azaola, 2005; Calvo, 2014). That crimes committed by women are often directly related to family poverty and the need to care for children has been suggested (Moloney et al., 2009). Single motherhood constitutes a determining factor in the process of social exclusion that leads many women to commit crimes (Calvo, 2014).

Figure 10. Incarcerated People Who Have Children and No Partner According to Gender and Year of Survey.

Source: prepared by the authors based on the Survey of Individuals Deprived of Liberty (CELIV/UNTREF, 2013 and 2019).

Another factor that accentuates women's previous situation of vulnerability is the number of children. In 2019, 24% of women had more than four children, while among men this percentage is reduced to 9%.

Figure 11. Number of Children of Incarcerated Persons According to Gender and Year of the Survey.

Source: prepared by the authors based on the Survey of individuals deprived of liberty (CELIV/UNTREF, 2013 and 2019).

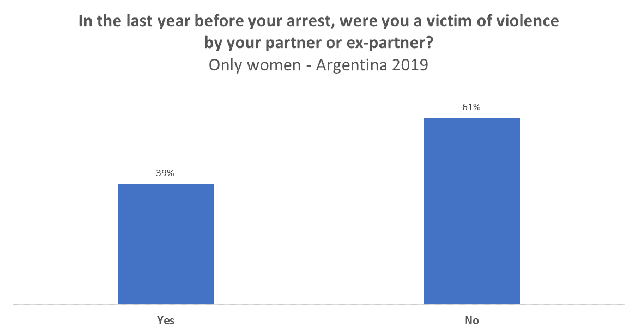

Finally, another axis of vulnerability linked to women's history of victimization is highlighted: in the year prior to the arrest, 39% of women had been victims of violence by their partners or ex-partners. This finding is consistent with several studies that reveal that intimate partner violence is an element that is present directly or indirectly in the majority of women in detention (Yagüe, 2007; Igareda, 2006). The high frequency of episodes of sexual abuse, family, and partner abuse in the lives of these women is highlighted (Bloom et al., 1994; Owen & Bloom, 1995; Yagüe, 2007).

Figure 12. Incarcerated Women Who Suffered Violence by Their Partner or Ex-partner in the Last Year before Their Arrest.

Source: prepared by the authors based on the Survey of Individuals Deprived of Liberty (CELIV/UNTREF, 2013 and 2019).

Discussion

This paper started from an original database that includes two surveys conducted by the Center for Latin American Studies on Insecurity and Violence (CELIV/UNTREF) in Argentina, in 2013 and 2019. The Survey of Individuals Deprived of Liberty has made it possible to explore and describe the effects that incarceration have on women in prison in two different time periods. The results of this study indicate that there are gender differences in the effects of incarceration on the inside, which are mainly crystallized in the behavior of nearby containment networks. For women, contact with their emotional environment is more limited than for men; many women do not receive visits or receive them more sporadically than men. In turn, access to conjugal visits, which involves other types of ties with the outside, poses greater challenges for women. The findings reveal that not only is the frequency of visits different between incarcerated men and women, but also the type of support received by each of them is different.

As has been indicated throughout the article, many of these results are in line with previous studies. Studies conducted regarding various countries' incarcerations confirm that women, more so than men, suffer abandonment by their most significant individuals (Lagarde, 1993; Azaola, 1996; Azaola & Yacamán, 1996; Muraskin, 2000). In this sense, specialists have affirmed that romantic partners desist more often when women are deprived of their liberty than when men are (Pinto, 1999; Galván et al., 2006). From a gender perspective, Galván et al. (2006) point to one possible explanation for this trend. In patriarchal cultures, women are typically responsible for caring for others and overseeing the family's moral values. In the case of women in prison, the behavior that resulted in their incarceration is seen as a violation of social and moral values. Therefore, in the eyes of others, they are not considered worthy of support and consideration but rather of rejection and exclusion. In this context, that the social stigma of women in confinement is greater than that of men is suggested (Galván et al., 2006).

Likewise, data suggest that the poor social support women receive from family and friends impacts their physical and emotional well-being (Galván et al., 2006). Of important note is that this conclusion cannot be directly inferred from the evidence presented in the article. However, it does indicate that women in prison are more likely to develop illnesses and report experiencing depression compared to men. These findings align with previous studies conducted in various confinement context across different countries, which show that the experience of imprisonment has a more significant impact on the deterioration of women's mental health and/or psychoemotional state (Antony, 2003; Cárdenas, 2011; Calvo, 2014). Although the lack of supportive directly causing women's well-being and/or their health status cannot be assumed, it does align with what the literature points out and recognizes as an influencing factor (Fernandez, 2017; Azaola, 1996).

The primary contribution of this article lies in its ability to contrast the findings from theoretical, qualitative, and/or other countries' contributions with those of Argentina, based on a quantitative approach, using a recent and original database. In addition, the observation is made that, in general, previous works on the subject have been carried out at different historical moments. The article highlights that the majority of premises remain relevant even in current confinement contexts.

Final Thoughts

This study does not aim to exhaust discussions on the subject, but rather to contribute to expanding knowledge, raising questions, and paving the way for new dialogues.

From the gender perspective that guides this article, the need to broaden the gender categories in data collection instruments to address the specificities of the non-binary population in confinement contexts is emphasized. Not doing so implies ignoring the fact that there are people deprived of their freedom with their own demands and problems that are not being considered.

In addition, there are opportunities to improve the quality of life of women who are deprived of their liberty and their supporting environment. The incarceration of women having a significant emotional impact, especially on their children should not be forgotten, as the daily bond is disrupted, and changes are observed in modes of subsistence, organization, and family dynamics. Given the necessity to prevent social disconnection, numerous researchers refer to the urgent need to explore potential alternatives to incarceration and to reconsider prison sentences from a perspective that enables the most vulnerable groups of women to break free from the cycle of condemnation, marginalization, and stigmatization. In this sense, the study highlights the importance of addressing this complex issue, which merits further in-depth research.

One of the primary recommendations arising from the results is the necessity to raise awareness among family members of incarcerated women regarding the significance of promoting and maintaining continuous and permanent contact with them, as this form of support often greatly benefits their physical and emotional well-being. Also crucial, correctional institutions should reconsider the use of visitation suspensions as a form of punishment and control, as such measures entail a range of adverse consequences for both the inmate population and the institution itself. The important thing will be to develop correctional policies with a gender perspective, which take into account the characteristics, needs and demands of incarcerated women through specific measures for them "that allow these women to improve their personal capacities and help them to fully exercise their citizenship rights" (Yagüe, 2007, p. 17).

At the same time, the results suggest an assessment of extreme vulnerability in the trajectories of women in confinement. These life experiences are characterized by limited resources for social inclusion, many of them marked by unemployment, teenage pregnancy and instances of harassment and violence. Against this backdrop, noting that psychological care is crucial is particularly important, as it is absent in almost all cases (Fernandez, 2017). This can lead to irreversible situations, as shown by studies that conclude that the probability of suicide is five times higher in battered women than in the general population of women (Kurz, 1989). Social welfare policies taking center stage in these environments and manifesting in the living conditions of incarcerated women is crucial, thereby preventing their near hegemonic replacement by the criminalization of poverty (Wacquant, 2001).

References

Almeda, E. (2017). Criminologías feministas, investigación y cárceles de mujeres en España. Universidad de Barcelona.

Alfonsín, J. (2015). Traslados al Anexo Psiquiátrico, una modalidad de sanción encubierta. In D. Sodini and S. Garbi (Coords.), Seguridad pública, violencias y sistema penal(pp. 79-89). Centro de Estudios en Política Criminal y Derechos Humanos –CEPOC–.

Antony, C. (2003). Panorama de la situación de las mujeres privadas de libertad en América Latina desde una perspectiva de género. En DPLF, CDHDF y CMDPDH (Comps.), Violencia contra las mujeres privadas de libertad en América Latina (pp. 57-75). Comisión de Derechos Humanos del Distrito Federal, Comisión Mexicana de Defensa y Promoción de los Derechos Humanos, A.C., y Fundación para el Debido Proceso Legal.

Antony, C. (2007). Mujeres invisibles: las cárceles femeninas en América Latina. New Society, (208), 73-86. https://bdigital.binal.ac.pa/bdp/artpma/mujeres%20delincuentes.pdf

Aranda, C. & Pando, M. (2013). Conceptualización del apoyo social y las redes de apoyo social. Revista de investigación en psicología, 16(1), 233-245. https://revistasinvestigacion.unmsm.edu.pe/index.php/psico/article/view/3929

Azaola, E. (1996). El delito de ser mujer. Plaza y Valdés.

Azaola, E. (2005). Las mujeres en el sistema de justicia penal y la antropología a la que adhiero. Cuadernos de Antropología social, (22), 11-26. https://doi.org/10.34096/cas.i22.4426

Azaola, E. & Yacamán C. J. (1996). Las mujeres olvidadas: un estudio sobre la situación actual de las cárceles de mujeres en la República mexicana. El Colegio de México.

Bloom, B., M. Chesney-Lind & B. Owen. (1994). Women in California Prisons: Hidden Victims of the War on Drugs. Informe del Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice, San Francisco, CA.

Butler, J. (1990). EI género en disputa. El feminismo y la subversión de la identidad. Editorial Paidós.

Calvo, E. d. M. (2014). Imprisonment. Impacto en las emociones y los cuerpos de las mujeres presas. Cuadernos de Trabajo Social, 27(2), 395-404. https://revistas.ucm.es/index.php/CUTS/article/view/43821

Cárdenas, A. (2011). Mujeres y cárcel: diagnóstico de las necesidades de grupos vulnerables en prisión. Universidad Diego Portales.

Carrillo, A. Q., García, J. N. & Salina, G. M. (2020). Discriminaciones de género en prisión. Programas socioeducativos para combatir la desigualdad. En: Díez, E.J. and Rodríguez, J. R. (Dirs.), Educación para el Bien Común: hacia una práctica crítica, inclusiva y comprometida socialmente (pp. 1008-1021). Octahedron.

CELS, Ministerio Público de la Defensa de la Nación, Procuración Penitenciaria de la Nación. (2011). Mujeres en prisión: los alcances del castigo. 1ª ed. Siglo Veintiuno Editores.

CELIV. (2019). Contextos de encierro en América Latina: una lectura con perspectiva de género. UNTREF.

Davis, A. Y. (1996). Incarcerated Women: Transformative Strategies. Black Renaissance, 1(1), 21-34.

Del Campo, M. L. & Navarro, A. (2012). El significado de la cocina en mujeres de clase media de Córdoba, Argentina. Una aproximación desde la teoría de las Representaciones Sociales. Perspectivas en Nutrición Humana, 14(2), 113-124. https://revistas.udea.edu.co/index.php/nutricion/article/view/15128

Fernández, A. (2017). Relationships among women in prison. Violence: types, consequences and acceptance. En: Añaños-Bedriñana, F. T. (Dir.) En prisión. Realidades e intervención socioeducativa y drogodependencias en mujeres (pp. 76-86). Narcea Ediciones.

Galván, J., Romero, M., Rodríguez, E. M., Durand, A., Colmenares, E. & Saldivar, G. (2006). La importancia del apoyo social para el bienestar físico y mental de las mujeres reclusas. Salud mental, 29(3), 68-74.

Gelsthorpe, L., & Morris, A. (2002). Women's Imprisonment in England and Wales: A penal paradox. Criminal justice, 2(3), 277-301. https://doi.org/10.1177/17488958020020030301

Igareda, N. (2006). Mujeres, integración y prisión. Boletín criminológico, (12), 1-4. https://revistas.uma.es/index.php/boletin-criminologico/article/view/8769

Instituto Nacional de las Mujeres de México y PNUD (2006), Garantizando los derechos humanos de mujeres en reclusión. INMUJERES.

Kurz, D. (1989). Social Science Perspectives on Wife Abuse: Current Debates and Future Directions. Gender and Society, 3(4), 489–505. https://www.jstor.org/stable/189766

Lagarde, M. (1993). Los cautiverios de las mujeres: madres, esposas, monjas, putas, presas y locas. UNAM.

Lombardo, M. A.; Rojas, F. & Sánchez, V. (2016). Consultoría para la Evaluación de eficiencia de los institutos penales de Paraguay administrados por el Ministerio de Justicia. Final evaluation report. Red2Red Consultores.

Matthews, R. (2003). Doing Time An Introduction to the Sociology of Imprisonment Edicions Bellaterra. Serie General Universitaria, 24.

Moloney, K. P., Van den Bergh, B. J. & Moller, L. F. (2009). Women in Prison: The Central Issues of Gender Characteristics and Trauma History. Public Health, 123(6), 426-430. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19493553/

Monclus, M. (2017). El arresto domiciliario como alternativa al encierro carcelario en el caso de mujeres embarazadas o madres de niños/as pequeños/as. En Di Corleto, J. (Comp.), Género y Justicia Penal (pp. 285-309). Didot Editions, CABA.

Morris, A. (1987). Women, Crime and Criminal Justice. Basil Blackwell.

Mullins, C. W. & Wright, R. (2003). Gender, Social Networks, and Residential Burglary. Criminology, 41(3), 813-840. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.2003.tb01005.x

Muraskin, R. (2000). The Pains of Imprisonment. Long-term Incarceration Effects on Women in Prison. En It's a Crime. Women and Justice (pp. 205-213). Prentice Hall Contemporary Justice Series.

Owen, B. & Bloom, B. (1995). Profiling Women Prisoners: Findings from National Surveys and a California sample. The Prison Journal, 75(2), 165-185. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0032855595075002003

Pinto, J. C. (1999). Cárceles y familia. La experiencia del penal de San Sebastián en Cochabamba. Diakonía.

Reyes, G. J. & Quispe, M. (2017). «Estuve desnudo y me cubristeis; enfermo, y me visitasteis; estuve en la cárcel, y vinisteis a mí». Temas Sociales, (40), 199-231. https://repositorio.umsa.bo/bitstream/handle/123456789/16331/Temas%20Sociales%2040.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Rodríguez, M. N. (2003). Mujer y cárcel en América Latina. En DPLF, CDHDF y CMDPDH (comp.). Violencia contra las mujeres privadas de libertad en América Latina (pp. 57-74). Comisión de Derechos Humanos del Distrito Federal, Comisión Mexicana de Defensa y Promoción de los Derechos Humanos, A.C., y Fundación para el Debido Proceso Legal.

Romero, L., Gracida, J. N., & Lara, C. B. (2014). Pagando culpas: vulnerabilidad de las mujeres reclusas de Tabasco. El Cotidiano, (186), 19-34. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/325/32531428008.pdf

Ruidíaz, C. (2011). Prisión y sociedad: mirada panorámica desde la perspectiva de género. Brocar. Cuadernos de Antropología social, (35), 255–266. https://doi.org/10.18172/brocar.1605

Sardinha, L. (2015). Este día es respeto y alegría: consideraciones sobre el género en el día de visita a las cárceles del Distrito Federal, Brasil. Nueva Antropología, 28(82), 103-123. https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=15943065006

Seear, N. & Player, E. (1986). Women in the Penal System. Howard League.

Vigna, A. (2011). Discriminación hacia personas privadas de libertad y liberadas. Informe Hacia un Plan Nacional contra el Racismo y la Discriminación. MEC, Dir. DDHH. AECID/PNUD.

Vigna, A. (2012). Análisis de datos del I Censo Nacional de Reclusos, desde una perspectiva de Género y Derechos Humanos. Mesa de Trabajo sobre Mujeres Privadas de Libertad.

Wacquant, L. (2001). The Penalisation of Poverty and the Rise of Neo-liberalism. European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research, 9, 401–412. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1013147404519

Yagüe, C. (2007). Mujeres, integración y prisión. Intervención basada en sus características, necesidades y demandas. Revista Española de Investigación Criminológica, 4(5), 1-23. https://reic.criminologia.net/index.php/journal/article/view/29