Inclusive Higher Education. A Review using Tree of Science1

[Version in English]

Educación superior inclusiva. Una revisión usando Tree of Science

Ensino superior inclusivo. Uma revisão usando Tree of Science

Received April 12, 2023

Accepted January 17, 2024

|

How to cite Ramírez, B. & Restrepo, P. A. (2024). Inclusive Higher Education. A Review using Tree of Science Ánfora, 31(57), 327-353. https://doi.org/10.30854/anf.v31.n57.2024.1059 |

Beatriz Ramírez Aristizábal 2 https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7297-9516 CvLAC https://scienti.minciencias.gov.co/cvlac/visualizador/generarCurriculoCv.do?cod_rh=0001337596 (Colombia) Paula Andrea Restrepo García3 https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2119-8656 CvLAC https://scienti.minciencias.gov.co/cvlac/visualizador/generarCurriculoCv.do?cod_rh=0000690813 (Colombia)

|

Abstract

Objective: This article aims at identifying the main contributions, gaps, and trends around inclusive practices in higher education. Methodology: A search in Scopus and the Tree of Science (ToS) algorithm was conducted to identify articles in the root, trunk, and branches. Results: The results revealed three subfields within the review of scientific production related to inclusive higher education: 1) aspects that influence the consolidation of more inclusive education; 2) inclusion of students with disabilities between barriers and opportunities; and 3) implications for consolidating more inclusive higher education practices. Conclusions: It is concluded that there is a need to generate more space for training and formation on the understanding of inclusive education and practices.

Keywords: inclusive education, higher education, pedagogical practice, barriers, diversity (obtained from the UNESCO thesaurus).

Resumen

Objetivo: en este artículo se busca identificar los principales aportes, vacíos y tendencias en torno a las prácticas inclusivas en la educación superior. Metodología: se realizó una búsqueda en Scopus y se aplicó el algoritmo de Tree of Science (ToS) para identificar los artículos en la raíz, tronco y ramas. Resultados: los resultados mostraron tres subcampos emergentes en la revisión de la producción científica en relación con la educación superior inclusiva: 1) los factores que influyen en la consolidación de una educación más inclusiva, 2) la inclusión de estudiantes con discapacidad: entre barreras y oportunidades, y 3) las implicaciones para la consolidación de prácticas de educación superior más inclusivas. Conclusiones: a partir de los estudios revisados, se concluye la necesidad de generar más espacios de capacitación y formación sobre las comprensiones de la educación inclusiva y las prácticas que de ellas se derivan.

Palabras clave: educación inclusiva; educación superior; práctica pedagógica; barreras; diversidad (obtenidos del tesauro de la UNESCO).

Resumo

Objetivo: este artigo busca identificar as principais contribuições, lacunas e tendências das práticas inclusivas no ensino superior. Metodologia: foi realizada uma pesquisa no Scopus e o algoritmo Tree of Science (ToS) foi aplicado para identificar artigos na raiz, no tronco e nos ramos. Resultados: os resultados mostraram três subcampos emergentes na revisão da produção científica em relação ao ensino superior inclusivo: 1) fatores que influenciam a consolidação de um ensino mais inclusivo, 2) a inclusão de alunos com deficiência: entre barreiras e oportunidades, e 3) implicações para a consolidação de práticas de ensino superior mais inclusivas. Conclusões: com base nos estudos revisados, conclui-se a necessidade de criar mais espaços de capacitação e formação sobre as compreensões da educação inclusiva e as práticas decorrentes delas.

Palavras-chave: educação inclusiva; educação superior; prática pedagógica; barreiras; diversidade (obtidas do tesauro da UNESCO).

Introduction

Discourses on inclusive education have been on the public agenda since 1990, with the “Global Declaration on Education for All” held in Jomtien, Thailand (Unesco, 1990). The conceptual transitions from that time to the present have been significant; among the main paradigm breakdowns, there is a change in the perspective of addressing differences. The approach moves from an integrative proposal to another on “some others” historically excluded, whom are required to be adapted and adjusted to become part of educational organizations, into a trend that focuses on how these institutions, conceived from the ideology of normality, have set up barriers that limit access, learning, and participation of individuals for whom they were not originally intended. The effective materialization of inclusive educational processes demands three main components: practices, policies, and cultures. Hence, there is a need to know the deployment of these components in recent years in higher education through a systematic analysis.

Changes related to these discourses have been significant in basic and secondary education, leading to their incorporation into educational policies that transform relations, didactics, and pedagogical practices at these educational levels. However, its influence in the field of higher education has been less important, given the competitive and meritocratic nature of university education in the international context.

In this sense, while universality has been promoted in basic education, it has been veiledly established in higher education that it applies only to a few, those considered to be “the most capable." In connection with this, Mareño (2021) states that the demand for productivity, excellence, and individual talent has generated in higher education a culture of ableism (p. 37, own translation), that is, a culture focused on the imperative of normality inherent in our societies.

In inclusive education, Slee (2012) recognizes a complex set of influences that contribute to its establishment as a field of study, but the review of scientific production shows a tendency to associate it with the education of people with disabilities, perhaps because, as a society, it has difficulties transforming our understanding of human differences apart from the normal-abnormal dichotomy. In this regard, research trends respond to an inclusion perspective related to neoliberal inclusionism (Waitoller et al., 2019) that promotes practices of selective or exclusive inclusion (Veiga-Neto & Lopes, 2011).

Therefore, this article emerges from the need to approach a systematic review of the phenomenon of inclusive higher education from the perspective of recent scientific production. We searched Scopus using the formula "inclusive education" AND "higher education" and found 471 articles. They were organized by the algorithm of the ToS (Tree of Science) (Robledo et al., 2022) to determine the most important subfields of research on inclusion in higher education. This process enabled the recognition of the most important conceptual advances to explain the role of inclusive perspectives in higher education, from early contributions to the most recent findings.

In three general ways, the scientific literature has addressed the phenomenon of inclusive higher education. Internal and external issues, particularly those affecting the disabled population, influence the consolidation of inclusive processes in the first subfield. A second subfield describes the disabilities associated with physical and architectural, attitude, pedagogical, and didactic barriers identified by students. Finally, some research highlights the need for inclusive training for professors and the use of ICT as a means of flexible educational processes, as they are essential to advancing the transformation of higher education systems from a more inclusive perspective.

Methodology

A systematic review of literature implies to collect, organize, evaluate, and synthesize available support on a subject of interest to identify topics of understanding, gaps and trends on a particular subject of study. For the literature review, the search equation “inclusive education” and “higher education” was used in Scopus to identify the most important papers on inclusion in higher education. It was established that concepts could be implicit in the title, keywords or abstracts, thus 471 articles were under study. After that, the web platform ToS (Tree of Science) ⸺a tool designed to facilitate the search of literature by an algorithm SAP4 and a theory of graphs (Robledo et al., 2022)⸺ was used to identify the most relevant papers on the object of study through the analysis of citation networks, and to identify three essential aspects that metaphorically can be associated with the tree (root, trunk, and branches).

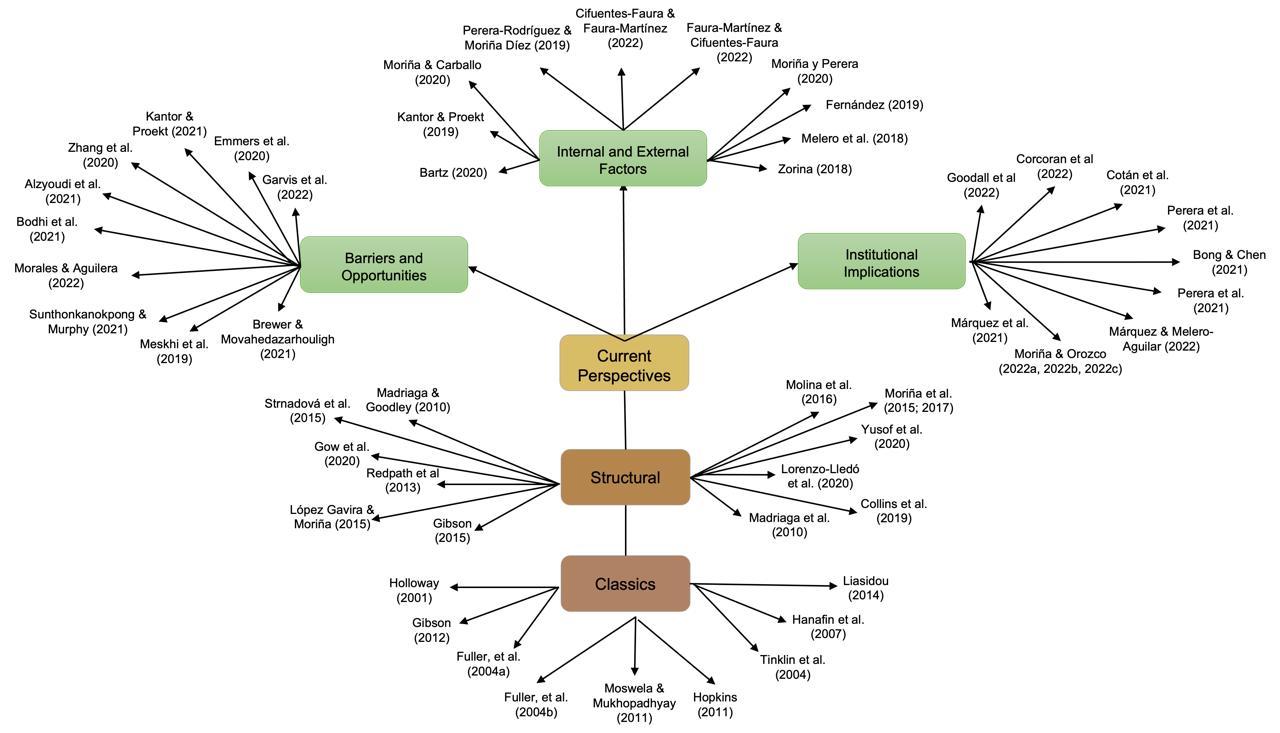

ToS provides a graph that reflects the importance of an article, according to the number of citations and publishing dates (Zuluaga et al., 2022). From this classification, it is possible to place at the root the articles that start the understanding of the object of study and based the theory as the ones of greatest citation; in the trunk, the structuring articles fulfill a double purpose: To cite and to be cited; and, finally, in the branches, the most recent studies and their comprehensive approaches. They are also the articles in which the most citations are made. The search on ToS allowed the identification of 10 articles in the root, 31 in the trunk, and three in the branches for a total of 34 articles, as Figure 1 shows.

Figure 1. Tree of Science in Inclusive Higher Education.

After the selection of these papers, data was systematized through a matrix that enabled the identification of key aspects, such as abstracts, objectives, methodology, results, and conclusions. This enabled a comprehensive understanding of how the processes of inclusion in higher education have been from different contexts, barriers, experiences of actors and challenges. The next step was to analyze the main aspects to identify the most relevant elements. This analysis was framed into a historical approach around the processes of inclusion in higher education to reveal different topics of understanding, tensions, and trends.

Results

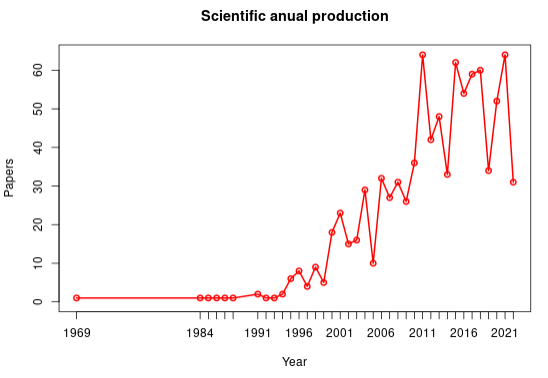

Figure 2 shows the number of articles published per year in Scopus. It was found that between 2010 and 2021 the scientific production in relation to the phenomenon of inclusive higher education had a significant growth, from 35 to more than 60 articles. It shows the importance and position of the phenomenon on the international floor over the last decade.

Figure 2.Annual scientific production.

Source: ToS (2022).

In relation to the authors, Table 1 shows the most referenced articles. Moriña from Spain is the most recurrent author (31 articles), followed by authors Ainscow (11 articles) and Slee (9 articles) from the United Kingdom.

Table 1. Authors by number of references.

|

Author |

Freq. |

Country |

|

Moriña, Anabel |

31 |

Spain |

|

Ainscow, Mel |

11 |

United Kingdom |

|

Slee, Roger |

9 |

United Kingdom |

|

Leyser, Yona |

7 |

United States |

|

Sharma, Umesh |

7 |

Australia |

|

Florian, Lani. |

6 |

United Kingdom |

|

Moliner, Odet. |

5 |

Spain |

|

Avramidis, Elias |

4 |

Greece |

|

Burgstahler, Sheryl |

4 |

United States |

|

Lipka, Orly |

4 |

Israel |

Referring back to the tree metaphor, we present the main findings below, taking into account their position within the tree (root, trunk, or branches). This enables us to comprehend the various viewpoints that approach inclusive higher education.

Root: Theoretical Foundations for Understanding Inclusive Higher Education

50% of the research placed in the root was conducted between 2001 and 2012. It focused on disability and the barriers students face in higher education, mainly from individual experiences. In this regard, Holloway (2001), explored the university's significant documentation to identify the aspects that enable a positive experience for students with disabilities, as well as those that lead to discriminatory and marginalizing practices.

One of the first systematic analyses of students’ experiences with disabilities in higher education was focused on learning barriers (Fuller et al.) (2004). The research presents statistical data on the quality and variety of learning experience, assessments of conditions associated with learning and evaluation of 173 students. Among the main findings, there is a need to pay more attention to issues related to parity and provision flexibility, and also to the staff capacity to identify and design reasonable adjustments according to recent disability legislation. Gibson (2012) focused especially on the learning experiences of first-year students with disabilities, their transitions from school to university, and positive and negative learning experiences at both levels.

The struggle of students with disabilities to access and participate in higher education remains a major concern for disability activists and researchers Moswela and Mukhopadhyay (2011). They registered the experiences of university students with disabilities in their struggle to access and participate in higher education, and reported their findings into six topics: Attitude, resource, structural barriers, policy-related issues, lack of support mechanisms, and lack of skills and knowledge. Hopkins (2011) also highlights this issue through the exploration of the narratives of students with disabilities and the barriers they face when trying to access curricula in tertiary education. These narratives state that they have to work harder than non-disabled students to overcome a wide range of physical, attitude, social, cultural and political barriers.

The understanding from the perspective of the rights of individuals with disabilities is another topic of research. Tinklin et al. (2004) discussed the state of policy for this population in higher education in Scotland and England. The researchers conclude that while there were definitive signs of progress in the development of students with disabilities, some areas need more attention, such as the need to challenge conventional notions of effective teaching and learning practices. Hanafin et al. (2007) argued that in the European context, the facilitation of more participation of historically marginalized groups has become a cornerstone of social policy. This approach has tended to focus on physical access and some technical support; however, the access is multifaceted and should include a review of pedagogical practices, as well as technological and personnel assistance.

The last approach, poorly explored, has been focused on critical studies on disability, since historically disability has been excluded from these analyses merely in the field of abnormality and individual pathology. Liasidou (2014) addresses some ideas from critical studies of disability to highlight the significance of adopting the theoretical and pedagogical foundations of Universal Design for Learning (UDL) to mobilize socially fair changes in higher education.

While it is true that Ground-based studies show progress on building a public policy around the process of inclusive education, progress is still needed to advance in infrastructure adaptation to ensure access and participation for all. As well as making adjustments at the pedagogical level, especially in curriculum design and evaluation systems, to provide quality at the end of an educational process. It is only in 2014 that the research turns to highlighting how certain dimensions of a social justice discourse should be included in a public policy discussion on inclusion and promote greater participation of students with disabilities in higher education (Liasidou, 2014).

Trunk: Structuring Understandings of Inclusive Higher Education

The structural analysis identified four main topics. The first one was focused on research from the voices of the actors on different ways to improve inclusion practices in higher education. The first reference was Redpath et al. (2013), who analyzed students’ perceptions about current services and barriers and provided suggestions for improving them. The research suggests a communication network to foster dialogue among actors to favor the student, as the core of these discussions, and to remark the importance in the long term of the objective of the institutions from the logic of the individual “reasonable adjustments” to move towards inclusive education for all. Strnadová et al. (2015) analyzed the types of support referred by students, including the role of the family, peers, and attendants. Participants also shared strategies to deal with their barriers and highlighted assertiveness, self-determination, and metacognition.

The second axis of understanding addresses research that goes beyond the perspective of rights. Gibson (2015) and Madrid & Goodley (2010) in the UK, Moriña et al. (2017) in Spain, and Gow et al. (2020) in South Africa emphasize the need for higher education to fill the gaps between the policy and its implementation for students with disabilities. Also, on the importance of problematizing the rights of public policies to reflect on the complexities and conflicts of inclusion and the design of a proposal on new pedagogical developments with a critical view on the impact of hegemony and the silenced voices of this people.

The third axis focuses on subjects, especially professors of higher education and students with disabilities, through a narrative-biographical methodological approach. Moriña et al. (2015) present the recommendations of 44 university students with disabilities, not only for adequate training of the professors but also to know about the disability itself and the ways to respond to the needs. Molina et al.(2016) analyze how professors respond to students with disabilities, identify barriers, and provide support that influence access, academic performance, and perceptions of their experiences in higher education. From this perspective, Lorenzo-Lledó et al. (2020) analyze the implementation of inclusive methodologies in university students with disabilities from the teaching posture. According to the professional category and their branch of knowledge, there are significant differences in perceptions.

A final topic focuses on research that emphasizes the challenges of higher education, where collegiate action and networking must be guarantees for the processes of transformation and flexibility that are required, in such a way that welcoming educational environments can be managed to facilitate the deployment of the capacities of each subject. From this perspective, Moriña (2017) and Madriaga et al. (2010) state the need to reflect on how the university should transit towards an inclusive scenario that demands the design of policies, strategies, processes, and practices to consolidate a culture aimed at involving people within the framework of an education for all.

Despite significant progress towards inclusive education through reasonable adjustments for all, Collins et al. (2019) contend that the adaptation of learning settings for individual students presents both organizational and personal challenges. Four main challenges were identified: (1) staff perception of resources that create too much dependence on students; (2) staff training needs; (3) low representation of students with visible disabilities; and (4) the need for inclusion beyond education to employment.

Branches: Inclusive Higher Education's Comprehensive Emergencies

Between 2018 and 2022, 30 papers from 332 articles on the branches appeared. We can group the most recent studies into three distinct trends. They allow us to go deeper into the tensions and compressions of inclusive higher education; in this way, both internal and external factors affect the consolidation of inclusive processes.

The first trend explicitly refers to the disabled population and reflects on the possibilities of inclusive education. The second refers to the barriers identified by students with disabilities associated with higher education. In this regard, it relates to three main aspects: physical and architectural barriers, professors’ attitudes, and pedagogical and didactic barriers. Finally, some research attempted to break the connection between inclusive education and disability. On the one hand, they introduce aspects related to social justice, the training of inclusive professors, and the use of ICTs as a mediation in flexible educational processes; on the other hand, they analyze factors to be considered in the consolidation of higher education institutions that move towards inclusive processes.

Influential Factors on the Consolidation of More Inclusive Education.

In the first branch, there are studies that approach to internal factors (attitudes, perceptions, concerns, qualities, conditions, among others) and external factors (environment, culture, policies, practices) that influence the possibility of achieving more inclusive educational processes. They establish a direct relationship between the concept of inclusive education and the education of the population with disabilities.

The first article of this branch shows a positive connection between the attitude of professors, the university environment, and spirituality (as an orientation of social altruistic value) to incorporate inclusive education into the context of India (Bodhi et al. 2021). It has some practical implications to emphasize the intention of inclusion. The educational organization must look for alternatives to influence the consolidation of a convenient attitude of professors towards inclusive education. Alzyoudi et al. (2021) analyze the attitudes of students called “typical development” in relation to their disabled fellows in the context of the United Arab Emirates. They identify negative attitudes that are justified from the requirement of university education that would directly affect the intentions of socialization and interaction towards this population. According to the findings, the knowledge of inclusive education policies does not positively influence these perceptions. In this way, there is a need to generate measures to promote the change of perceptions and to get more acceptance; thus, training processes are proposed in relation to inclusive education and the importance for the consolidation of more inclusive societies.

Morales and Aguilera (2022) point out the need to identify the perceptions of students with disabilities, professors, and managers towards inclusive education processes to identify barriers and their facilitators. Garvis et al. (2022) refer to the teachers training of early childhood in the Swedish university context, it establishes the importance of knowing the beliefs of training teachers on inclusive education. Sunthonkanokpong and Murphy (2021) analyze the concerns of teachers in training about the inclusion of students they call “diverse” in their classrooms; they focus mainly on the lack of resources and the work with disabled populations. They also highlight the lack of research on teaching training in contexts of diversity.

Brewer and Movahedazarhouligh (2021) present the experiences of students with intellectual disabilities and their development in post-secondary education. They refer to these new opportunities in university contexts through the discourse of inclusive education. They state the importance of knowing the experiences of these students to identify barriers, challenges, strengths and needs of such programs and generate transformation processes.

Another aspect of understanding has to do with the mobilizations associated with the practices for the approach to inclusive educational processes. In this regard, Kantor and Proekt (2021) identify that while university professors have motivational or emotional preparation for the development of a more inclusive education, the lack of practical skills becomes a barrier to the implementation, and generates resistance and rejection. They also recognize a greater inclusion of social and humanities professors in contrast to natural and exact sciences professors. As a result, they propose a model of psychological preparation of university professors for the implementation of inclusive education including a motivational-valorative component, an emotional and a practical component. Similarly, Emmers et al. (2020) study the relationship between professors' attitudes, self-effectiveness, and behavior toward inclusive higher education. They state the importance of policy reforms, focusing on the need for the practical experience of professors in training to develop procedural skills for inclusive educational processes.

Some research insists on the need to consider the fundamental skills of a professor to respond to diversity in inclusive education; others state the importance of technological mediation as an opportunity for the diversification of teaching in higher education. Zhang et al. (2020) argue that most traditional models of higher education are not adequately adapted to the needs of people with intellectual disabilities, and they recognize in blended learning the potential for consolidating inclusive education systems that are flexible and adjusted to learning opportunities. Meskhi et al. (2019) analyze the limitations and opportunities for the development of e-learning in the inclusive education system in Russian universities and recognize flexibility as a condition to ensure access, learning, and participation of different population groups that otherwise would not have access.

Inclusion of Students with Disabilities: Between Barriers and Opportunities.

The studies in this branch acknowledge the importance of understanding the educational realities of the disabled population in a university context. Bartz (2020) highlights the socio-economic inequality this population faces in higher education, especially their needs for complementary care by the health system, as they are limited in the time and cost they demand. The author also emphasizes the importance of addressing the architectural barriers in institutions as well as barriers to the spatialization of educational sets as aspects that interfere with learning. A third aspect is the learning resource, since, although in many cases, the institutions have educational platforms to support teaching processes, few professors carefully select the learning resources and analyze accessibility conditions. This latter aspect is also studied by Perera-Rod and Moriña (2019) in relation to the support and obstacles of new technologies in the education and academic lives of university students with disabilities, as well as the need for training professors for their pedagogical use.

Several authors identified professors' attitudes as an obstacle to promoting the learning and participation of students with disabilities; thus, they highlight the need for further training and the development of inclusive teaching methods. Furthermore, the use of Universal Design for Learning (UDL) is suggested as an alternative to thinking of more flexible, relevant, and accessible curricula (Bartz, 2020; Moriña & Perera, 2020; Moriña & Carballo, 2020; Melero et al., 2018).

Moriña and Carballo (2020), Fernández (2019), and Melero et al. (2018) analyze, from the perspective of students with disabilities, different facilitators and obstacles from their own experiences and call for institutionality and transformations for the university towards a more inclusive education. Moriña and Carballo (2020) refer to the need for accessibility of university settings, planned transition processes, work orientation services, positive attitude of professors, development of inclusive practices, use of technologies, and the need to train professors on inclusion and disability. Melero et al. (2018) reinforce these findings through the life stories of students with disabilities. They refer to the main barriers during their university study: physical barriers and the ones associated with professors.

Zorina (2018) presents different strategies for eradicating barriers to education in Russian universities. The author proposes a methodology for their sustainable elimination and refers to an inclusive infrastructure for training, communication, and socialization. It is also stated that there is a need to ensure full academic access to high-quality education through educational programs adjusted to the needs of the population, including psychological and pedagogical support. And remarks on the importance of removing attitude barriers to promote actions to facilitate socialization and interaction among differences. Kantor and Proekt (2019) identify the lack of willingness of peers to study with people with disabilities, the significant communication difficulties, the limitations for teaching organization due to heterogeneous groups, and the lack of knowledge, mediation, and educational resources for such processes.

Finally, Faura-Martínez and Cifuentes-Faura (2022), and Cifuentes-Faura and Faura-Martínez (2022) propose an instrument to evaluate the state of inclusive education in each university and to know the degree of curricular suitability and accessibility, as well as the resources and inclusion projects. This will allow us to classify institutions according to progress in inclusive education, especially in terms of the quality of specific measures to help students with disabilities or other special needs.

Implications for Consolidating More Inclusive Practices in Higher Education.

This latter branch enables an approach to those dimensions of higher education that need to be considered to move towards inclusive educational processes. On this basis, it is possible to identify at least four trends: the need to think about timely, relevant, and harmonious transformations between higher education and the workplace about social justice; the use of technology as a powerful mediator in the processes of universal access to curricula; the need to train professors with an inclusive profile for changes in educational practices; and, finally, the general conditions to consolidate inclusive higher education institutions.

Goodall et al. (2022) and Corcoran et al. (2022) refer to the need to think more comprehensively about the inclusive perspective, not limited to educational settings, and consider aspects related to the transition of employment and equal opportunities. Goodall et al.(2022) state that much remains to be done in the creation of inclusive education and employment settings; they point out the need for dissemination and training processes for staff in both fields. Corcoran et al. (2022) assert that measuring inclusive education solely by enrolment is no longer sufficient, as it is crucial for ensuring study opportunities and facilitating the transition to employment. The authors propose that instead of perpetuating homogeneity in the world of education and work, higher education can use the inherent requirements to increase social justice and equity (Corcoran et al., 2022, p. 69, own translation).

In terms of accessibility possibilities, Cotán et al. (2021), Perera et al. (2021), and Bong and Chen (2021) refer to the use of technology as a mediator of inclusive academic management processes. Despite the growing use of ICT in higher education over the past few years, Bong and Chen (2021) assert that professors still require training in creating digital learning resources and environments that are accessible and welcoming to all. This includes teaching them about the Universal Learning Design (ULD), laws, standards, and guidelines for accessibility, as well as differences in the educational setting.

Perera et al. (2021) value the use of technological media and virtual environments in implementing inclusive educational practices. They refer to a broad sense of inclusive education, not exclusively for people with disabilities, since they identify that this type of mediation facilitates flexible regulation of the pace and intensity of learning according to each student's interests and individualities.

A third aspect refers to the need to have inclusive professors in higher educational institutions (Márquez & Melero, 2022; Moriña & Orozco, 2022a; Moriña & Orozco, 2022b; Moriña & Orozco, 2022c). Marquez and Melero (2022) investigate professors' knowledge and beliefs about inclusive education and find that most of them do not know about it. Furthermore, they state that

[...] The goodwill, sensitivity, and professional commitment of the professors are not enough to face the diversity in the university classrooms if they do not have the knowledge and skills to develop more inclusive curricula. (p. 840, own translation).

This knowledge about inclusive education differs significantly between disciplines; therefore, it is important to have a teaching training program that is not homogeneous but can respond to the specific needs of professors in each area.

Márquez and Melero (2022) identify three categories regarding professors' beliefs: 1) equal access to university opportunities that all students should have; 2) inclusive education as care for students with disabilities; and 3) a broader vision about everyone's participation and success. The findings point to the need to think about the necessity of improving professors’ training processes, starting and deepening debates on the meaning and implications of inclusion (Márquez & Melero, 2022, p. 842, own translation).

Moriña and Orozco (2022a, 2022b, and 2022c) state that inclusive professors recognize diversity in its complexity, and they do not focus on the permanent difference between students with or without disabilities; they remark that the most inclusive teaching practices are those that promote active and participatory interaction. On the other hand, the researchers identify that an inclusive professor facilitates learning for all students, has skills that are not only professional but also personal, and directly influences student success. They also emphasize the need for “well-informed and well-trained” teaching staff to provide an education that responds to diversity and enables progress in the design of educational practices for all.

Finally, some studies related to the design of indicators facilitate the evaluation of institutional processes and the implementation of actions, plans, and projects to transform higher education systems towards inclusive educational processes (Cifuentes-Faura & Faura-Martínez, 2022; Márquez et al., 2021). Cifuentes-Faura and Faura-Martínez (2022) work on a dynamic indicator of inclusive education that sets a ranking of those universities best prepared to offer inclusive resources in Spain. Márquez et al. (2021) propose a system of indicators that will make it easier for university institutions to self-assess their students' inclusion conditions in terms of institutional culture, equitable access, student-centered learning, well-being and participation, mobility and employability, and academic achievement. They also state that progress towards the construction of universities where everyone can learn and participate is an unstoppable task that many institutions do not know how to deal with (Márquez et al., 2021, p. 33, own translation).

Conclusions

From this review, it is possible to understand that the discourse of inclusive education tends to move towards a direct connection with the education of the population with disabilities instead of institutions and practices that value, recognize, and act according to diversity, singularity, and heterogeneity. The studies identified mostly associate inclusive education with the population, their needs, and their requirements.

Most of the identified barriers are the attitudes, beliefs, prejudices, and perceptions of professors about differences associated with disability as barriers; other research findings highlight physical and architectural conditions without basic accessibility and are focused on pedagogical and didactic mediations. Standard students are the target audience for institutional planning that takes into account human diversity in various scenarios.

Most studies conclude that professors require training with an inclusive profile. This involves processes for both their human condition and their differences, as well as those that emphasize the development of pedagogical and didactic skills to design and deploy curriculum with universality and diversification.

Another identified opportunity was the flexibility of pedagogical mediations of ICT in education, as well as the use of e-learning and b-learning models as options to promote the implementation of accessibility for educational resources and teaching processes, taking into account various conditions such as time, language, and resources.

In addition, instruments and indicators are emerging to contribute to institutional self-assessment processes, make visible barriers, establish possible actions, strategies, plans, projects, and policies to implement, and thus move towards the consolidation of increasingly inclusive higher education institutions.

Finally, several studies demonstrate significant progress in implementing the public policy of inclusive higher education. However, it is imperative to go beyond the parameters of public policy and act cooperatively to change beliefs, customs, and behaviors that limit the right to an equalitarian education.

The systematic review of inclusive higher education identifies the need to broaden and deepen its theoretical and epistemological foundations, examining the connections between inclusive education and various perspectives such as the critical theory of education, poststructuralism, feminist theories, cultural studies, postcolonial and decolonial studies, queer theory, and crip theory. It is possible to advance towards understanding human differences and diversity apart from the dichotomy of normal and abnormal. That contributes to the consolidation of a culture of reception and appreciation within academic, pedagogical, research, relationship, and management practices for diversity to foster the presence, learning, and participation of all and everyone in the daily institutional life as a condition of social justice.

References

Alzyoudi, M., Opoku, M. P., & Moustafa, A. (2021). Inclusive Higher Education in United Arab Emirates: Will Perceived Knowledge of Inclusion Impact Positively on University Students’ Attitudes Towards Learning with Peers with Disabilities? Frontiers in Education, 6, 1-10. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2021.793086

Bartz, J. (2020). All Inclusive? Empirical Insights into Individual Experiences of Students with Disabilities and Mental Disorders at German Universities and Implications for inclusive Higher Education. Education Sciences, 10(9), 1-25. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10090223

Bodhi, R., Singh, T., Joshi, Y., & Sangroya, D. (2021). Impact of Psychological Factors, University Environment and Sustainable Behaviour on Teachers’ Intention to Incorporate Inclusive Education in Higher Education. International Journal of Educational Management, 36(4), 381–396. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijem-02-2020-0113

Bong, W. K., & Chen, W. (2021). Increasing Faculty’s Competence in Digital Accessibility for Inclusive Education: A Systematic Literature Review. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 0(0) 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2021.1937344

Brewer, R., & Movahedazarhouligh, S. (2021). Students with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities in Inclusive Higher Education: Perceptions of Stakeholders in a First-Year Experience. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 25(9), 993–1009. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2019.1597184

Cifuentes-Faura, J., & Faura-Martínez, U. (2022). Mapping of Technological and Support Resources for the Inclusion of Students with Disabilities in Higher Education Institutions. International Journal of Disability, Development, and Education, 0(0), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/1034912x.2022.2095358

Collins, A., Azmat, F., & Rentschler, R. (2019). “Bringing Everyone on the Same Journey”: Revisiting Inclusion in Higher Education. Studies in Higher Education, 44(8), 1475–1487. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2018.1450852

Corcoran, T., Whitburn, B., & Knight, E. (2022). Inherent Requirements in Higher Education: Locating You in Us. Perspectives Policy and Practice in Higher Education, 26(2), 69–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603108.2021.1986166

Cotán, A., Carballo, R., & Spinola-Elias, Y. (2021). Giving a Voice to the Best Faculty Members: Benefits of Digital Resources for the Inclusion of All Students in Arts and Humanities. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 0(0), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2021.1991492

Emmers, E., Baeyens, D. & Petry, K. (2020). Attitudes and Self-Efficacy of Teachers Towards Inclusion in Higher Education. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 35(2), 139–153. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2019.1628337

Faura-Martínez, U., & Cifuentes-Faura, J. (2022). Building a Dynamic Indicator on Inclusive Education in Higher Education. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 37(4), 690–697. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2021.1929237

Fernández, A. C. (2019). Investigación narrativa para contar historias: líneas de vida de estudiantes universitarios con discapacidad. Revista de la Educación Superior, 48(192), 23–47. https://doi.org/10.36857/resu.2019.192.927

Fuller, M., Healey, M., Bradley, A., & Hall, T. (2004). Barriers to Learning: A Systematic Study of the Experience of Disabled Students in One University. Studies in Higher Education, 29(3), 303–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070410001682592

Garvis, S., Uusimaki, L., & Sharma, U. (2022). Swedish Early Childhood Preservice Teachers and Inclusive Education. In H. Harju-Luukkainen, N. B. Hanssen, & C. Sundqvist (Eds.). Special Education in the Early Years: Perspectives on Policy and Practice in the Nordic Countries (pp. 87–100). Springer International Publishing.

Gibson, S. (2012). Narrative Accounts of University Education: Socio-Cultural Perspectives of Students with Disabilities. Disability & Society, 27(3), 353–369. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2012.654987

Gibson, S. (2015). When Rights are Not Enough: What is? Moving Towards New Pedagogy for Inclusive Education within UK Universities. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 19(8), 875–886. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2015.1015177

Goodall, G., Mjøen, O. M., Witsø, A. E., Horghagen, S., & Kvam, L. (2022). Barriers and Facilitators in the Transition from Higher Education to Employment for Students with Disabilities: A Rapid Systematic Review. Frontiers in Education, 7, 1-15. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2022.882066

Gow, M. A., Mostert, Y., & Dreyer, L. (2020). The Promise of Equal Education Not Kept: Specific Learning Disabilities – The Invisible Disability. African Journal of Disability, 9, 1-10. https://doi.org/10.4102/ajod.v9i0.647

Hanafin, J., Shevlin, M., Kenny, M., & Neela, E. M. (2007). Including Young People with Disabilities: Assessment Challenges in Higher Education. Higher Education, 54(3), 435–448. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-006-9005-9

Holloway, S. (2001). The Experience of Higher Education from the Perspective of Disabled Students. Disability & Society, 16(4), 597–615. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687590120059568

Hopkins, L. (2011). The Path of Least Resistance: A Voice Relational Analysis of Disabled Students’ Experiences of Discrimination in English Universities. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 15(7), 711–727. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603110903317684

Kantor, V.Z., & Proekt, Y. L. (2019). Inclusive Higher Education: Socio-Psychological Well-Being of Students. The Education and Science Journal, 21(2), 51–73. https://doi.org/10.17853/1994-5639-2019-2-51-73

Kantor, V.Z. & Proekt, Y. L. (2021). Inclusive Educational Process at the University: Theoretical and Experimental Model of Teachers’ Psychological Readiness. The Education and Science Journal, 23(3), 156–182. https://doi.org/10.17853/1994-5639-2021-3-156-182

Liasidou, A. (2014). Critical Disability Studies and Socially Just Change in Higher Education. British Journal of Special Education, 41(2), 120–135. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8578.12063

Lorenzo-Lledó, A., Lorenzo, G., Lledó, A., & Pérez-Vázquez, E. (2020). Inclusive Methodologies from the Teaching Perspective for Improving Performance in University Students with Disabilities. Journal of Technology and Science Education, 10(1), 127-141. https://doi.org/10.3926/jotse.887

Madriaga, M., & Goodley, D. (2010). Moving Beyond the Minimum: Socially Just Pedagogies and Asperger’s Syndrome in UK Higher Education. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 14(2), 115–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603110802504168

Madriaga, M., Hanson, K., Heaton, C., Kay, H., Newitt, S., & Walker, A. (2010). Confronting Similar Challenges? Disabled and Non‐Disabled Students’ Learning and Assessment Experiences. Studies in Higher Education, 35(6), 647–658. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070903222633

Mareño, M. (2021). El capacitismo y su expresión en la educación superior. Revista Argentina de Educación Superior, 13(23), 24-43. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/descarga/articulo/8247039.pdf

Márquez, C., & Melero, N. (2022). What are their Thoughts About Inclusion? Beliefs of Faculty Members About Inclusive Education. Higher Education, 83(4), 829–844. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-021-00706-7

Márquez, C., Sandoval, M., Sánchez, S., Simón, C., Moriña, A., Morgado, B., Moreno, I., García, J. A., Díaz, V., & Elizalde, B. (2021). Evaluación de la Inclusión en Educación Superior Mediante Indicadores. REICE, Revista Iberoamericana Sobre Calidad Eficacia y Cambio en Educación, 19(3), 33–51. https://doi.org/10.15366/reice2021.19.3.003

Melero, N., Moriña, A., & López, R. (2018). Life-Lines of Spanish Students with Disabilities during their University Trajectory. The Qualitative Report, 23(5), 1127-1145. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2018.3092

Meskhi, B., Ponomareva, S., & Ugnich, E. (2019). E-learning in Higher Inclusive Education: Needs, Opportunities and Limitations. International Journal of Educational Management, 33(3), 424–437. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijem-09-2018-0282

Molina, V. M., Perera, V. H., Melero, N., Cotán, A., & Moriña, A. (2016). The Role of Lecturers and Inclusive Education. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 16(1), 1046–1049. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-3802.12361

Morales, P. & Aguilera, M. C. (2022). Percepción de actores que participan en programas educativos inclusivos en educación superior. Revista Internacional de Humanidades, 11(1), 81-91. https://doi.org/10.37467/gkarevhuman.v11.3043

Moriña, A. (2017). Inclusive Education in Higher Education: Challenges and Opportunities. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 32(1), 3–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2016.1254964

Moriña, A. y Carballo, R. (2020). Universidad y educación inclusiva: recomendaciones desde la voz de estudiantes españoles con discapacidad. Educação & Sociedade, 41, 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1590/es.214662

Moriña, A., Cortez-Vega, D., & Molina, V. (2015). What if we could Imagine the Ideal Faculty? Proposals for Improvement by University Students with Disabilities. Teaching and Teacher Education, 52, 91–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2015.09.008

Moriña, A., López-Gavira, R., & Morgado, B. (2017). How do Spanish Disability Support Offices Contribute to Inclusive Education in the University? Disability & Society, 32(10), 1608–1626. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2017.1361812

Moriña, A., & Orozco, I. (2022a). Inclusive Learning Strategies at University: The Perspective of Spanish Faculty Members from Different Knowledge Areas. C&E, Cultura y Educación, 34(2), 231–265. https://doi.org/10.1080/11356405.2022.2031786

Moriña, A., & Orozco, I. (2022b). Teaching Experiences of Inclusive Spanish STEM Faculty with Students with Disabilities. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 21, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10763-022-10276-4

Moriña, A., & Orozco, I. (2022c). Portrait of An Inclusive Lecturer: Professional and Personal Attributes. Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research, 0(0), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/13511610.2022.2070133

Moriña, A., & Perera, V. H. (2020). Inclusive Higher Education in Spain: Students with Disabilities Speak Out. Journal of Hispanic Higher Education, 19(3), 215–231. https://doi.org/10.1177/1538192718777360

Moswela, E., & Mukhopadhyay, S. (2011). Asking for too much? The Voices of Students with Disabilities in Botswana. Disability & Society, 26(3), 307–319. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2011.560414

Perera-Rodríguez, V.H., & Moriña, A. (2019). Technological Challenges and Students with Disabilities in Higher Education. Exceptionality, 27(1), 65–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/09362835.2017.1409117

Perera, V. H., Moriña, A., Sánchez-Díaz, N., & Spinola-Elias, Y. (2021). Technological Platforms for Inclusive Practice at University: A Qualitative Analysis from the Perspective of Spanish Faculty Members. Sustainability: Science Practice and Policy, 13(9), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13094755

Redpath, J., Kearney, P., Nicholl, P., Mulvenna, M., Wallace, J., & Martin, S. (2013). A Qualitative Study of the Lived Experiences of Disabled Post-Transition Students in Higher Education Institutions in Northern Ireland. Studies in Higher Education, 38(9), 1334–1350. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2011.622746

Robledo, S., Zuluaga, M., Valencia, L. A., Arbelaez-Echeverri, O., Duque, P., & Alzate-Cardona, J.-D. (2022). Tree of Science with Scopus: A Shiny Application. Issues in Science and Technology Librarianship, 100, 1-7. https://doi.org/10.29173/istl2698

Slee, R. (2012). La escuela extraordinaria. Exclusión, escolarización y educación inclusiva. Morata.

Strnadová, I., Hájková, V. & Květoňová, L. (2015). Voices of University Students with Disabilities: Inclusive Education on the Tertiary Level – A Reality or a Distant Dream? International Journal of Inclusive Education, 19(10), 1080–1095. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2015.1037868

Sunthonkanokpong, W. & Murphy, E. (2021). Pre-Service Teachers’ Concerns about Diversity. Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education, 13(4), 1097–1109. https://doi.org/10.1108/jarhe-06-2020-0193

Tinklin, T., Riddell, S., & Wilson, A. (2004). Policy and Provision for Disabled Students in Higher Education in Scotland and England: The Current State of Play. Studies in Higher Education, 29(5), 637–657. https://doi.org/10.1080/0307507042000261599

Unesco. (1990). Declaración mundial sobre educación para todos. Satisfacción de las Necesidades Básicas de Aprendizaje. Unesco.

Valencia-Hernandez, D. S., Robledo, S., Pinilla, R., Duque-Méndez, N. D. & Olivar-Tost, G. (2020). SAP Algorithm for Citation Analysis: An Improvement to Tree of Science. Ingeniería e Investigación, 40(1), 45–49. https://doi.org/10.15446/ing.investig.v40n1.77718

Veiga-Neto, A. & Lopes, M.C. (2011). Gubernamentalidad, biopolítica e inclusión. En R.A. Cortés Salcedo, D.L. Marín Díaz & S. Castro-Gómez (Comp). Gubernamentalidad y Educación. Discusiones contemporáneas (pp.105-126). IDEP.

Waitoller, F. R., Beasly, L., Gorham, A. & Kang, V. Y. (2019). Hacia una educación inclusiva interseccional: el caso de los estudiantes afroamericanos y latinos con discapacidades en Chicago. Publicaciones, 49(3), 37-55. https://doi.org/10.30827/publicaciones.v49i3.11403

Zhang, Y., Rebrina, F., Sabirova, F., & Afanaseva, J. (2020). Blended Learning Environments in Inclusive Education at the University. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning, 15(21), 145-161. https://doi.org/10.3991/ijet.v15i21.16013

Zorina, E. E. (2018). Eradicating the Barriers to Inclusive Higher Education. The Education and Science Journal, 20(5), 165–184. https://doi.org/10.17853/1994-5639-2018-5-165-184

Zuluaga, M., Robledo, S., Arbelaez-Echeverri, O., Osorio-Zuluaga, G. A., & Duque-Méndez, N. (2022). Tree of Science - ToS: A Web-Based Tool for Scientific Literature Recommendation. Search Less, Research More! Issues in Science and Technology Librarianship, 100, 1-10. https://doi.org/10.29173/istl2696