Creative Writing as a Form of Psychosocial Mediation: A Bet from the Sociocultural Vision of Human Cognition1

(English Version)

La escritura creativa como forma de mediación psicosocial: una apuesta desde la visión sociocultural de la cognición humana

Escrita criativa como uma forma de mediação psicossocial: um compromisso a partir de uma visão sociocultural da cognição humana

Received on 26/03/2023

Accepted on 26/05/2023

|

To cite this article: Carmona, D. E et al., (2024). Creative Writing as a Form of Psychosocial Mediation: A Bet from the Sociocultural Vision of Human Cognition. Ánfora, 31(57), 197-221. https://doi.org/10.30854/anf.v31.n57.2024.1055 |

Diana Esperanza Carmona Gonzalez2 https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6436-854X CvLAC https://scienti.minciencias.gov.co/cvlac/visualizer/generarCurriculoCv.do?cod_rh=0001427500 Colombia Daniela Vanegas Cortés3 https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2246-0900 CvLAC: https://scienti.minciencias.gov.co/cvlac/visualizer/generarCurriculoCv.do?cod_rh=0001552447 Colombia Herminzul Jimenez Mahecha4 https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5735-0445 CvLAC: https://scienti.minciencias.gov.co/cvlac/visualizer/generarCurriculoCv.do?cod_rh=0000718548 Colombia |

Abstract

Objective: To recognize creative writing as a tool for psychosocial mediation and as a space to enhance cognitive skills; through which the realities experienced by young people are interpreted through the stories created in the writing workshop oriented within the framework of the project "Weaving political capacities for transitions in territories, in Ovejas, Sucre". Methodology: The realities co-constructed by young people during the sessions of the creative writing workshop are made visible, which involved the participation of seven young people belonging to the Youth Corporation Promoting Peace (CORJUP), which operates in the village of Villa del Carmen and in the urban area of Ovejas. The postulates of phenomenology proposed by the author Maurice Merleau-Ponty, and Paulo Freire's popular education, are taken as reference for the work developed with young people. Results: First, the territorial altar constituted a device for creativity; second, metaphor appears as a way to narrate the unnamable aspects of young people's realities; third, the workshop is configured as a possibility for psychosocial mediation; and fourth, it is evident that the gathering allows young people to strengthen cognitive skills that enable them to appropriate the constructed knowledge and recognize its importance for transforming the lived reality. Conclusions: Creative writing seeks to be a sort of stage for transforming the very present that communities inhabit. It is assumed as a space to promote the cognitive resources that make social interaction possible, it is configured as the visionary power to find in the gathering a possibility to transcend conflicts. It also acknowledges that writing shows, elaborates, and transcends the capacity to mediate between individual reality and sociocultural practices.

Key words: Creative writing; mediation; cognition; youth; peace (obtained from the UNESCO thesaurus).

Resumen

Objetivo: reconocer la escritura creativa como una herramienta de mediación psicosocial, y como un espacio para potenciar las habilidades cognitivas; desde las cuales se interpretan las realidades vividas por los jóvenes a través de los relatos creados en el taller de escritura orientado en el marco del proyecto «Hilando capacidades políticas para las transiciones en los territorios, en Ovejas, Sucre». Metodología: se visibilizan las realidades co-construidas por los jóvenes durante las sesiones del taller de escritura creativa, que contó con la participación de siete jóvenes pertenecientes a la Corporación Juvenil Promoviendo Paz (CORJUP), la cual tiene su campo de acción en la vereda Villa del Carmen y en el casco urbano de Ovejas. Se toman como referencia los postulados de la fenomenología propuesta por el autor Maurice Merleau-Ponty, y la educación popular de Paulo Freire, como fundamento para el trabajo desarrollado con los jóvenes. Resultados: primero, el altar territorial constituyó un dispositivo para la creatividad; segundo, la metáfora aparece como forma de narrar lo innombrable de las realidades de los jóvenes; tercero, el taller se configura como una posibilidad de mediación psicosocial; y, cuarto, se evidencia que la juntanza posibilita a los y las jóvenes fortalecer habilidades cognitivas que permiten apropiarse del conocimiento construido, y reconocer la importancia de este para transformar la realidad vivida. Conclusiones: la escritura creativa procura ser una suerte de escenario para transformar el presente mismo que habitan las comunidades. Se asume como espacio para impulsar los recursos cognitivos que hacen posible la interacción social, se configura como la potencia vidente de encontrar en la juntanza una posibilidad para trascender los conflictos. Reconoce, además, que la escritura muestra, elabora y trasciende la capacidad de mediar entre la realidad individual y las prácticas socioculturales.

Palabras clave: escritura creativa; mediación; cognición; juventud; paz (obtenidos del tesauro de la UNESCO).

Resumo

Objetivo: reconhecer a escrita criativa como uma ferramenta de mediação psicossocial e como um espaço para aprimorar as habilidades cognitivas, a partir das quais interpretar as realidades vividas pelos jovens por meio das histórias criadas na oficina de escrita realizada como parte do projeto «Hilando capacidades políticas para las transiciones en los territorios, en Ovejas, Sucre». Metodologia: as realidades construidas pelos jovens durante as sessões da oficina de escrita criativa são tornadas visíveis, com a participação de sete jovens pertencentes à Corporación Juvenil Promoviendo Paz (CORJUP), cujo campo de ação abrange a vila de Villa del Carmen e a área urbana de Ovejas. Os postulados da fenomenologia proposta pelo autor Maurice Merleau-Ponty e a educação popular de Paulo Freire foram tomados como referência para o trabalho desenvolvido com os jovens. Resultados: em primeiro lugar, o altar territorial se constituiu em um dispositivo para a criatividade. Em segundo lugar, a metáfora aparece como uma forma de narrar o inominável nas realidades dos jovens. Em terceiro lugar, a oficina se configura como uma possibilidade de mediação psicossocial. E, em quarto lugar, fica evidente que o encontro possibilita aos jovens o fortalecimento de habilidades cognitivas que lhes permitem se apropriar do conhecimento construído e reconhecer sua importância na transformação da realidade vivida. Conclusões: a escrita criativa busca ser uma espécie de cenário para transformar o próprio presente que as comunidades habitam. Ela é assumida como um espaço para promover os recursos cognitivos que possibilitam a interação social, configurando-se como o poder vidente de encontrar no encontro uma possibilidade de transcender os conflitos. Também reconhece que a escrita mostra, elabora e transcende a capacidade de mediação entre a realidade individual e as práticas socioculturais.

Palavras-chaves: escrita criativa; mediação; cognição; juventude; paz (extraído do dicionário de sinônimos da UNESCO).

Weaving the Word in Rural Colombia

From the scenarios of political transition in which Colombia finds itself, since the signing of the peace agreements in 2016, it is necessary to recognize not only the effects derived from the armed conflict, but also the mediation processes that have emerged in the territory, for this specific case, from the young people and their creative writing processes. That is the central issue that will be addressed in this paper, which arises from the research process developed in the heart of the Montes de María, specifically in Ovejas, Sucre, from the project "Spinning political capacities for transitions in the territories".

Ovejas is a municipality where the mountains cross the skies and settle poetically in the minds of those who observe a foggy sunrise that covers the town. The red sunset fills with hope because the night is coming to refresh the atmosphere and give air to the bodies. Its population is 23,436 inhabitants (Municipal Mayor's Office, 2020), of which a total of 18,507 people have been officially recognized as victims of the armed conflict (UARIV, 2021). This data speaks for itself, it accounts for the high level of affectation that this region has suffered, the largest of which is forced displacement. However, it is a municipality where its people, despite the difficulties, have found ways to get up and move forward through various mediation alternatives.

Ovejas is a municipality that smells of tobacco and sesame, two renowned crops that have also long supported families. Products such as yams, cassava, green beans, eggplant, pumpkin, watermelon, sweet pepper, chili peppers, and honey from bees, which are sown and cultivated in the mountains of its 11 districts, 23 villages, and 14 hamlets with the blessing of peasant's hands, also adorn the streets (Municipal Mayor's Office, 2020).

Flor del Monte, Chengue, Don Gabriel, Almagra, San Rafael, Canutal, La Peña, and Canutalito are some rural settlements with challenging access roads that have allowed access to understand the resistance and ways to resurface after violence. In the municipality of Ovejas, this has been present since the 1930s, when the unions resorted to weapons (Aguilera, 2013); later, in the 1940s, violence between political parties also occurred, and in the 1960s, with the struggle of the National Association of Peasant Users -ANUC (Méndez, 2017). Finally, in the 90s, violence reached its peak in Colombia, and for this area, a continuous struggle for the territory and a greater incidence between 1990 and 2005. While the population is currently in the process of transitioning towards peace, it is no secret that situations of violence persist in the area. Some residents even indicate that "[...] in the Montes de María, we have not yet lived through the post-conflict" (personal conversation with a land claimant leader, 2021).

Some of the main armed groups present in the early stages of the violence in the municipality of Ovejas were the Revolutionary Workers' Party (PRT), the Free Homeland Movement (MPL), and the Socialist Renewal Current (CRS). After the 1990s, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia People's Army (FARC-EP), the National Liberation Army (ELN), the United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC) Heroes Block of the Montes de María, and, more recently, the Gaitanista Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (AGC). As a result of the actions of these groups, there were multiple affectations in the municipality that left, among the main victimizing events, forced displacement, massacres, forced disappearance, land dispossession and child recruitment.

Additionally, in periods of greater violence, it was very typical for the Ovejera community to be excluded or singled out by other regions, as expressed by an older woman, "[...] At that time, we were called guerrillas. If you were riding in a taxi and asked where you were from, you wouldn't dare say Ovejas because they called us guerrillas." (personal conversation, 73-year-old sheepwoman, 2022, own translation). The growing outbursts of violence in the territory made the Montes de María a vulnerable area.

Based on all the problems caused by violence, the Program for the reconstruction of the social fabric in post-conflict zones in Colombia and, specifically, the project Spinning political capacities for transitions in the territories between 2019 and 2022. This aims to "Develop political capacities for transitions in the territories, based on democratic mediations of social conflicts, focused on reconciliation and the construction of stable and lasting peace" (Sánchez-Jiménez et al., 2021). Through this project, scenarios of community participation emerged to reconstruct the social fabric, which linked various actors, including women, social groups, productive organizations, and young people. With this last group, spaces were sought that shed light on the need to spread the word, weave knowledge, and perceive the world beyond the reality that many were accustomed to living.

The intention to portray through writing what happened in the territory arises from the participant's observation of an anthropologist who, through popular, street, and mountain literature, begins to weave spaces for feedback from the creative writing workshop in Maniguaje. It advances a process of recognition of the different ways of living and recreating reality, understanding that "[...] Writing as a form of representation of the universe is capable of being interpreted by and from infinite ways of seeing" (Cobaleda& Agudelo 2017). This also implies that through the writing of popular and academic realities, the written experience is configured as an exploration that also implies "[...] interrelating and combining the verbal with the visual and auditory" (Cobaleda & Agudelo, 2017). Mediation scenarios are then proposed for peacebuilding, where writing as a tool and space for interaction allows territories to transform their present reality.

Relevant elements of popular education proposed by Paulo Freire were used as references to conceptually base the process; others related to the phenomenology of perception postulated by Maurice Merleau-Ponty. Finally, autoethnography was used to prepare this article, as regards the articulation of the narrative from the researcher as author.

From Freire's approaches, his postulates of an education that values the lived experience of the actors are relevant. Its forms of identification with community and popular interests and values, from which the world is read, are not always perceived, and studied in the dominant model of banking education (Freire, 2004, p. 48). The emancipatory interest of creative writing can be understood as addressing the reasons for conflict and the possibilities of developing collective activities, which are not only responses to violence but can be ways to overcome those circumstances of violation.

Now, as for Merleau-Ponty, the connections that are established between the sense of experience as a situated perception of a consciousness that is, at the same time, a body to a region is resumed, with a sketch of the world that is accessed through gesture, from the singularity of what is lived. In the words of Merleau-Ponty (1985):

I understand others through my body, as it is through my body that I perceive "things." The meaning of the gesture, thus "understood," is not behind it; it is confused with the structure of the world that the gesture designs and that I take on my own; it is exhibited on the same gesture. (p. 203).

From the presence of the body as a gesture, the significance of being in the world is only understandable because there are tacit, previous elements to which consciousness is related. It assumes them with a projection of universality shareable with others through bodily perception and through attempts to embody them in language as a linguistic gesture. In this way, the conception of the world is not an event founded by isolated consciousness, but an expansion of experience that becomes correlative to the threads with which common language manages to make it transmissible. The concreteness of the phenomenon of communication through the linguistic gesture makes it possible at the same time, on the one hand, that the discourse does not translate "[...] in which it speaks, a thought already done, but consumes it" (Merlau-Ponty, 1985, p. 195), so that the senses of the speaking word and the spoken word can be differentiated; and, on the other hand, for those who understand the discourse, it happens that we have the power to understand beyond what we spontaneously think.

Therefore, being in the world allows us to know the gestural significance immanent in words and to recognize that "[...] the word is in a certain place in my linguistic world" (Merlau-Ponty, 1985, p. 197). If we exist as a possible perceiving consciousness, as mentioned, we are so to the extent that we have a standard body, gestures, and language that constitute us. At the same time, we update them by the very fact of discovering ourselves as part of the world of things but open to the exploration beyond its finitude and in the projection of the mystery of the body that transcends it.

The incorporation of the conceptual references related to autoethnography is due to the relational commitment that positions the narrator as a participant in a situation and a social environment. There, the researcher is perceived and interacts through discursive actions that constitute her role as the facilitator of a pedagogical strategy that simultaneously serves as a setting for the encounter with young people who are the protagonists of new searches and trajectories. As noted, the three conceptual references converge in terms of the social character from which the discursive actions are conceived and the possibilities of producing meaning for the agents. Not from the development of individual psychological skills but from the broader horizon of higher psychological capacities derived from participation in the various everyday social practices that people develop.

Methodology

Popular Narrative: Deep Voice as Territorial Chanting

I like peace processes; for me, peace is like the bird that sings in the morning: resplendent and fresh. It is like the sunrise after the rain. It is like the smell of wet soil or like the smell of mom's food. It is that hug that makes you think that everything will be fine. (Arlenis Genis, young man belonging to CORJUP, 2022).

Approaching rural communities, where people's needs are perceived as far away, is a kind of resistance space in which the risk of speaking other languages is taken. Through Participatory Action Research (IAP), it was possible to listen to the deep voice of the reality brewing from the collective resonances, which have expanded over the years. Young people are that portion of the population between the ages of 17 and 24 who are finding their identity through interaction with others. Youth is to have the possibility of opening their minds to new ways of conceiving the world, using everyday spaces to build scenarios that move towards peace. This was the population participating in the creative writing workshop, from which the development of this writing emerged. The group with which the workshop is carried out, rather than having been chosen under comparable selection criteria, was consolidated by affinity and taste for writing; its particularity is that in their free time, they work on sweet pepper, yam, and other crops in family plots. However, in their youthful life and leadership, they have found the power to unite, not to stop creating ways that lead them to think about the territory.

On the one hand, there are some first-semester students of Philosophy and Business Administration, a young woman who likes crafts and jewelry; on the other hand, there are young people who are just graduating from school, and, like a seed, there is a 12-year-old boy who takes part in the workshops and who begins to learn how a social or youth organization can be achieved. As a particularity evident in the group, there is the desire to express, be able to talk, and recognize that their community space and the region where they live, Montes de María, are more than war and fateful stories, as evidenced by the media. There is a fondness for ancestral identity and self-expression, discovering that many actions can be transformative; in this case, writing can transform individual and collective realities.

These young people's stage of action is the village of Villa del Carmen, better known in the municipality of Ovejas as «La Santa». We find the need of young people to narrate their territory to recognize that they are interested in artistic environments, such as the ability to externalize sensations and experiences. This led to the creation of the pedagogical strategy "Creative Writing Workshop", which is the main instrument for consolidating information. It all started in the Youth CORJUP (Youth Corporation Promoting Peace) group that emerged in 2021. Additionally, because they belong to the Ecumenical Network of Women for Peace (REMPAZ), the young people decided to form an alternative and inclusive project that would allow them to work for the shepherd youth. For them, it was important to find a space where they could express themselves and be independent of any political or organizational flag since, as some say, "[...] we had already been working a lot, but we did not find reasons to continue; sometimes the leaderships are not clear or good" (Youth of CORJUP, 2022).

After listening to the reasons and finally observing the shortcomings and limitations in the territory, the workshop was installed in February 2022 to unleash the creativity of young people. The main objective is to foster, through writing, narrative spaces for literary creation around the peasant and individual memory of the territory. In a context of silence, where many things are not told, speaking perhaps has been denied because only the elderly are heard, and silencing youth and childhood has been part of the "urbanity of Carreño". It is essential to recognize that, given young people's absent oral capacity, this proposal sets a precedent for written and oral expression. While writing creatively gives rise to reflection and inner experience, it is important to develop the power of language to read what is written and to share. For the young people of CORJUP, it becomes important to co-create and be part of the planning of activities; there, they found the Sunday meeting the power to redefine the role of social projects in the territory.

In addition to the above, inclusive activities need to be co-constructed and designed from the territorial symbols present in the territorial altar. Space was designed with objects for the recognition of the territory and observations of practices, which allowed observing and recognizing knowledge and trades such as weaving hats, chairs, and backpacks; the preparation of typical dishes such as the mote de queso, eggplant salad, bean rice, and chili pea; products cultivated in the region such as honey from bees, tobacco, garlic, sweet chili, avocado, yam, sesame; among other foods and objects that are of importance in the construction of collective and symbolic representations for the inhabitants of the municipality of Ovejas.

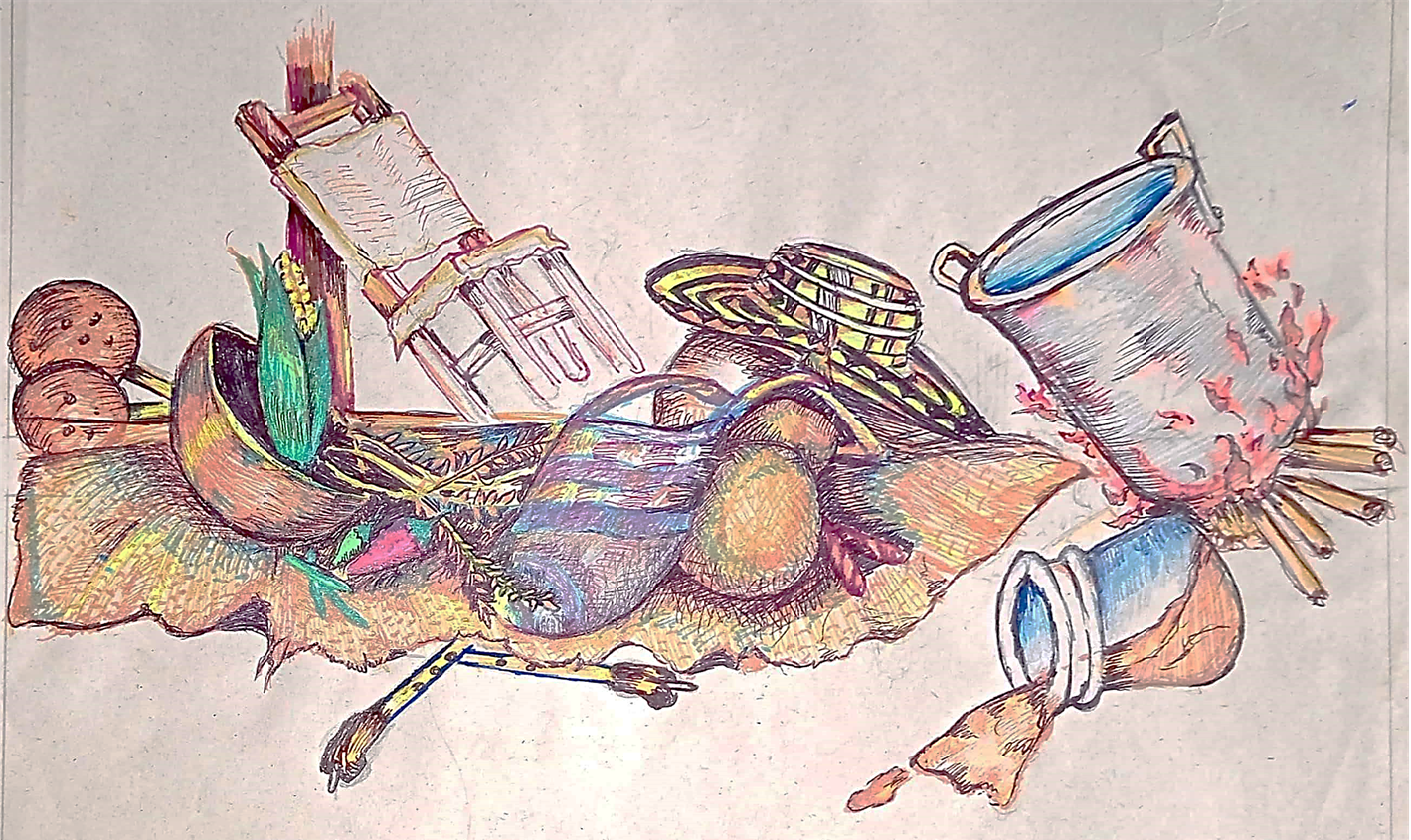

The path of writing and understanding their environment was just beginning. All roads led to Ovejas, like the land that forged their peasant spirits and identities. "[...] if you ask me, I am a peasant. I do not deny it. I feel part of my tradition" (Youth of CORJUP, 2022, own translation). With this expression, the work began. Thinking about the power of the symbols that appear on the territorial altar, each one chooses their food or object, giving it an origin and some characteristics (Figure 1).

Figure 1.Illustration inspired by the territorial altar.

Source: prepared by José Aníbal Rivero Salcedo for the Booklet "Popular Narratives for Peacebuilding," 2022.

Subsequently, and with the creation of characters, it is invited to know what a story is, to socialize some that allow working on famous and peasant narration, and the inner voice as a possibility of healing. For example, to address the recognition of the territory and the popular voice, it was proposed that the story "The Arrows" by David Sánchez Juliao be read. The reading inspired the young people to let their voices come to the surface; popular expressions like no joda’ , erda, mondá, «pelao,ven te echo un cuento», among others, arose to generate a more pleasant dialogue in which they had no prejudices about expressing their feelings and internalizing who they were and what we were. «Costeñol», a term that identifies the way of speaking and expressing oneself in the communities located on the Atlantic coast of Colombia (and which the Caro y Cuervo Institute recognizes as a dialect that corresponds to a variation of Spanish in the Colombian Caribbean) some words denote a meaning in this particular context, and are used with an innate ability to transmit an identity characteristic or, as pointed out in the work carried out by De la Ossa and De la Ossa (2021), "[...] a 'sentipensante' dialect, that is, the 'costeño' speaks feeling and feels speaking; hence it's linguistic and bodily expressions that escape the understanding of those who do not have Caribbean roots" (p. 25).

Thus, through the language and its dialect, Costeñol, young people had more confidence in those who guided the process, not because we were the «seños» (Name given to teachers in the municipality), but because it implied making known our practices and our ways of speaking to name the world. Therefore, the capacity of writing as a mediator from various socio-cultural and psychosocial aspects was evident since the dialogue from the territorial perspective began to grow. The young people enunciated their practices, and each time, it was more fun for them to write, share, and resignify what their characters were narrating, in addition to the meanings they discovered in their narratives. While this happened, the researcher's body was charged with meaning, words, and actions typical of the inhabited environment. Here, autoethnography makes sense as a space for dialogue with the community, as the power to bring universities and academia closer to community scenarios, understanding that reality from the researcher as a body that interacts. Thus, "[...] the body is a sort of expressive space that intertwines with other human bodies, with the living and with other things, which ultimately corresponds to the world itself" (Ferrada, 2019, p. 161, own translation).

In this sense, joint work with young people increasingly involved intertwining individual thoughts with collective ones; thus, writing was taking shape. In this way, creative writing and research were woven around autoethnography as a power to glimpse and allow for an expanded "[...] conception to accommodate both personal and/or autobiographical narratives, as well as the experiences of the ethnographer as a researcher - whether separately or combined - situated in a social and cultural context" (Blanco, 2012, p. 55, own translation).

In addition to this latent need to understand the world of young people, beyond just carrying out actions from scriptural encounters, it is preponderant to recognize the power of popular education in social fabric reconstruction contexts. This implies understanding that there is not only one reality in the world since there are many worlds, many lives, and many bodies. There are as many readings of the context as bodies walking and living the heartbeat of their territory's identity. It makes sense that those who work in or have approached these contexts, to paraphrase Mejía (2014), are endowed with a critical education that can be implemented throughout society. An education that helps to understand that if we work hand in hand with communities from their “oppressed” realities and locations, a transformation of that location can be achieved to co-construct more just societies (Mejía, 2014, pp. 5-6).

At this point, the perspectives from social research and the researcher's position in the workshop strengthen with the exercises elaborated on during the practical, creative writing sessions. There is no premise to write, no writing savvy where the feedback that was co-constructed is judged; simply, as the writing styles were distinguished, some horizons were unfolded to achieve a narrative of their own, with an inner voice the size of the youthful realities of the participants.

As previously related, the construction of the emerging stories and popular narratives had each participant's stories as protagonists; in their individualities, they allowed themselves to express what they felt regarding the reality of the world, their world. So, sharing the experience was a significant constituted space within the community-academy relationship, which supported a learning scenario around the fact that "[...] it is the individual himself who generates and builds his learning" (Chapel, 2016, p. 52, own translation). In this sense, each participant in their creative writings learned to narrate and, finally, built their way of internalizing what their writings wanted to convey about their places of enunciation.

Recognizing the narratives of the context is necessary to contribute to the transmission of social and cultural knowledge in the territories. These, in turn, are constituted as scenarios of social interaction that lead to the exchange of thoughts, actions, and individual conditions to clarify the powers of bodies in constant interaction with others. "Visible and mobile, my body is situated among the things; it is one of them. It belongs to the fabric of the world, and its cohesion is that of a thing" (Merleau-Ponty, 1964, p. 17, own translation); it is at this point that the interrelation between phenomenology and autoethnography becomes meaningful. Therefore, the experience of others could not be narrated without linking the feeling and being of the researcher in the field, without glimpsing that individual writing triggers collective writings of common territories, conversations, and social constructions that become constituted cultural practices.

From what is proposed in this article, the human condition, by relating, exchanging thoughts, and co-constructing, implies that human cognition is not seen from the subjects' individuality but is naturally mediated by interaction with other individuals. That is where the power of coming together, collective creation, and famous and community education lie as transformative settings and facilitators of narratives that enable socio-cultural exchange. Thus, it can be said that the psychic does not merely correspond to individuality; on the contrary, it could be argued that we recognize ourselves in "[...] a dialogical world that crosses the threshold of the subject as an individual being, insofar as its construction as a social being carries with it the identity of the collective, its actions and connected movements" (Sánchez-Jiménez et al., 2021, p. 97).

In addition to this and starting from the importance of creative writing as a space for exchange, interaction, and creation among young people, it is essential to express that writing as art allows individuals to mediate their internal and external, public, and private, community or family conflicts to solve any psychosocial damage that may emerge from some events. In the case of Ovejas, they are framed in the armed conflict as a scenario of territorial dispute and armed violence until now.

Writing heals, saves, transforms, transfers, and installs itself in the minds of those who practice it; it is not lucky for those who risk writing that they can transmit to rural communities the learning and explorations about writing they have acquired over time. This is the power, the gain, and the learning: to go beyond the reality already perceived, already built, and already planned for a subject, to get out of that mold of life where from the instituted forms one cannot do one thing or another. Expressing is thus here the power of writing as a psychosocial mediator, as mentioned by Sánchez-Jiménez et al. (2021)

[...] a relational world goes beyond the individual as a psychic being and is isolated from its interactive context. To say that someone or something acts from the psychosocial point of view is to speak of a construction of coordinated actions through which every creation, or the result of said creations, is responsible for the interacting parties. (p. 97, own translation).

This relationship between individuals and bodies recognized from a common history creates scenarios of exchange where they increasingly find meaning in resolving conflicts, making the territory's problems visible, and finding answers to some of the youth's unknowns.

Results

Creative Writing as a Mediator of Peace

Peace is transparent, it is not seen, but it exists.

Peace tastes like water, “to nothing”, but everyone likes it and it is vital.

Peace is like a dog, if it is your inner peace, it is your best friend.

Peace is like smoke, the one that comes from Mom's stove.

Even if they are always the same ingredients, it gives things a special touch "similar to love." (Marlon Genis, young man belonging to CORJUP, 2022, own translation).

Multiple learnings arise from community life. Thinking about academia at the service of people has to do with the present educational resistance, from the places that it is up to researchers and professionals from various disciplines to investigate. Contrary to other ways of producing knowledge, this article emerges from the narratives created by the young participants of the creative writing workshop, nurtured among the mountains, and always interested in narrating the other ways of conceiving culture and its territory.

The Territorial Altar as a Device for Creativity

The practices inherent in the identity of Ovejas played a fundamental role in designing the pedagogical strategy. In this sense, the workshop's execution was framed in the altar as a power of identity and community fabric, which manifests itself as a symbolic narrative to fill the sacredness of the territory with meaning through objects and representative and identifying foods of the place. From there, a narrative collage is crafted, which, in turn, is a "patchwork quilt"; fragments of identity are woven from the word to the writing. This allowed the participants whose identities have been embodied in this article to display their imaginations since it is considered essential to bring their essence and voice to their literary creations and thoughts. By bringing objects and food to life, describing rice as a "[...] blond-haired character [...] who likes to be in the countryside a lot, feels very comfortable there" (Marlon Genis), or talking about tobacco as a "[...] big, humble old man, well-presented as a politician in the campaign" (Brayan Palencia, own translation), important creative elementswere involved, as expressed by Vygotsky (1990), "[...] imagination is always structured with elements taken from reality" [own translation]. Thus, we saw how young people's previous experiences, in relation to these elements of the territorial altar, made possible materials for their imagination and the display of scriptural skills that even they did not know.

Finally, a narrative collage was built that became part of the essence of the workshop since it is not only reached as a product of the pedagogical strategy but also allows a retrospective of the altar in a creative narrative. The short film "The Unnamable: The Makeup of Reality" also comes from this collage. It was directed by Katherine Andrea Vidal Pino and presented at the Manizales International Film Festival in November 2022. This narrative collage highlights the individual stories of the participants in the workshop, where there are narratives such as Maxwell José Duque Escobar by Marlon Genis, Meanwhile in the Game by Arlenis Genis, Stories and Memories by Osnaider Ortega, The Burning Tobacco by Brayan Palencia Peña; White joy, by Dina Peña; and Maraca Maraquín Mercado, by Andrea Mercado.

In these stories, it was possible to show that creativity as an innate aspect of human beings stands out as a call to continue transforming the territory through art. In this regard, Vygotsky also proposed different ways of representing reality when reaching adolescence. Activities typical of childhood, such as play and drawing, migrate towards creative expressions such as writing and music, which are related to more subjective and personal experiences (Vygotsky, 1990) that also enhance the imaginative capacity. In the words of Limiñana (2008), "The richer man's experience, the greater the material his imagination will have" (p. 40, own translation).

These writings were authored by young men and women or pelaos, as they are usually called, triggered in the visibility of their perceptions regarding the reality of their territory; for example, in Stories and Memories, the author Osnaider Ortega shows his perception regarding how to name a group of bagpipers:

[...] By changing the subject and remembering Benvolio's old stories, he said he was part of a piping group called Los Desterrados, a group of veterans. While there, the old man told us that he had a beautiful maraca, and even the condemned man gave it a name: he called it macaraquita. Until now, they are inseparable; they are for each other (p. 18, own translation).

The importance of the territory and culture in the lives of the young people of Ovejas is evident, as they form the foundation of what they learn and how they acquire such knowledge. As Ocampo (2011) states, the study of the learning process should include the study of culture, the body, and emotions.

Finally, the creative writing workshop allowed the development of cognitive skills such as creativity, understanding, and expression and became a space for meeting, interaction, and motivation. Along the same lines, Tacca (2016) describes some approaches to how young people learn and concludes that learning is linked to the frequency of stimuli and emotions they experience. He argues that when a class (or in this case, an encounter) is accompanied by positive emotions, it becomes a priority for young people, as indeed was the creative writing workshop.

Metaphor as a Way of Narrating the Unnamable

The exiles are a way of mentioning how, in many contexts, the possibility of sowing the land was snatched away. In times of conflict, many moved from the vicissitudes suffered and were banished; there, immersed in writing, is the writer's interpretation of his environment and the stories he narrates. Other stories, like this one, show that we are talking about the time of the armed conflict; only for young people, it is more feasible to do it from a literary story, using metaphors, synonyms, alliterations, and other resources that possibly make the way of naming what they or their families lived less dense. In this regard, Zambrano et al. (2019) argues that "[...] creative imagination allows them to feel the "freedom" to alter everything that is already known and to enter a new context of many possibilities" (p. 70, own translation).

Thus, writing allowed young people to express themselves from their subjectivity, not only to address negative experiences but also to tell stories of hope. In the story Meanwhile, in the game, Arlenis Genis reveals that it is always possible to give second chances.

At the end of the story, I can tell you that Zoe can do great things and knows very well that she is made of body and soul, so she can know and give herself the opportunity to trust others. Zoe knows that she is a crybaby to show that there are good people, and she knows that she is almost scrawny and dwarfed to make it known that with those qualities, she can change the world.

In his language (Costeñol), he shows that it is possible to bring everyday life into the story, writing giving voice to his context. A space that conveys security and protects what the workshop intended, making visible the multiple ways of perceiving reality. Emotions occupied a main place in the workshop; allowing them to be expressed gave greater meaning to the young people's experiences, who found in it a space to feel understood and recognized. As Martínez and Vasco (2011) mention, "[...] by understanding feelings, better ethical and political principles can be formulated capable of reducing affliction and increasing the well-being of society" (p. 193, own translation)

In essence, this narrative gift allows us to observe that, although, in the beginning, none of their individual stories mentioned the time of dispossession, conflict, violence, and displacement that they lived in the Montes de María, these events were reflected in the memories of their families; the legacy of their ancestors impresses on them the need to show what happened. In such a way, it was found that metaphorical language served as a resource for expression, which also enhanced, as Valenciano (2019) mentioned, other skills such as motivation, creativity, and reflective thinking. In the fragment of the reader's guide that was co-constructed with the pelaos, they wanted to explain to whoever read some elements that are found throughout the story:

To camouflage (metaphorize) the period of the armed conflict in the Montes de María, it was decided that each game represents a way of responding to the victimizing events that occurred in the territory, which in the collage is represented as the elephant.

In this case, metaphor is more than a literary resource; as Pousa et al.mention, it becomes a bridge to what is meant. (2020) “[…] writing is, in turn, riddled with metaphors and images that disguise what is sometimes difficult to remember, say and feel” (p. 58, own translation). The foregoing refers and alludes to the following section:

And so Maxwell believed that all people were good, but when he grew up, he realized that was not true because neither cassava, yam, corn nor life grows under the shade of the elephant. That is why he defends agriculture like a fine hen that passes by, watching that the sparrow-hawk does not take her chickens (Marlon Genis, 2022, own translation).

Creative Writing as a Form of Psychosocial Mediation

The creative process managed to give context to the story, setting the stage for the Montes de María. In the fragments created by the young people, it is possible to perceive that the psychosocial mediations created by individuals begin to become spaces for common encounter, where weaving is the key to recognizing the vitality of belonging to the same space, feeling part of the network of the world where every act associated with an individual touches an entire community; understanding the reality of those who have had to suffer other realities.

The written word became an element of psychosocial mediation, as mentioned by Pousa et al. (2020), “Words have the power to bring about change, change that happens when awareness of who we are and who others are is broadened” (p. 64, own translation). This was precisely what the participants could evidence: changes in their way of perceiving, narrating, and interacting in their present realities. Creative writing spaces became environments of self-knowledge and recognition of others.

As the collective writing narrates, "And yes, the shadow of the elephant grows when the evening falls, and with it, the earth darkens... but not hope!" The bodies do not cease to want to dress in another reality, to exclaim that it is possible to find other words, other lands, and other airs that renew the past and transform the future. In a context affected by violence, peacebuilding appears as a prevailing need, as expressed by the young people who participated in the creative writing workshop:

Pelao 11: Let history remain in history.

Pelao 12: And that history does not repeat itself.

Pelao 13: Interior cleaning to be able to clean the territory.

Traveler: What are you looking for?

Maxwell: Peace. (CORJUP et al., 2022).

Starting precisely from the needs of the context, peacebuilding is one of the first order. In this sense, emotions, and feelings around it emerged in the meetings; translating them into writing allowed us to corroborate that for young people peace is a daily decision. Understanding that every human decision is the product of both emotional mechanisms and cognitive processes, the young people expressed that they could define what actions to carry out and what not to avoid repeating the history of violence and bet on a future of peace. As Damasio (2005) puts it: "[...] emotions and feelings do not have a crystal ball to see the future. However, deployed in the proper context, they become harbingers of what may be good or bad in the near or distant future.” (p. 143, own translation).

"What would have happened if the violence had not reached Ovejas?" With this question, one of the young people highlights the vitality of writing: that space to extol the present, to turn one's eyes and mind to other realities, to understand that peace is in a mote of cheese, or the honey cultivated by the farmers of Chengue, and in the narratives of the farmers of Ovejas. It could not be overlooked to recognize that it is possible to install a capacity, to recognize the innate knowledge of narrating through common languages, of knowing that it is possible to transform the past, the present, and the future. The creative writing workshop is then consolidated as a form of psychosocial mediation, enhancing the capacity.

[...] to build forms of transformation of conflicts, and they are possible when communities come together to find alternatives that generate life and new forms of language to relate to others and favor psychological, social, cultural, and political coexistence (Sánchez-Jiménez et al., 2021, p. 93, own translation).

The Power of Collaborative Writing

Juntanza appears as a power to transform social reality. It was evident the possibility of weaving through language the realities of silence and institutional precariousness. It is possible to resist and let oneself be found by inspiration in the Ovejas-style breakfast with cassava and sesame seeds, or in lunch with eggplant salad and pumpkin rice, and what to say about a good meal of spicy turkey with cassava and yam! The mountain breath accompanies all this, the smell of wet earth, and the edge of the machete with which, in the sun and water, the parents and these "peelers" go to the mountain to look for that piece of sky that gives them the hope that a different future is possible. Creating that future in complicity with others was a possibility in the workshop. It became evident that creativity is not a solo task but a process that is socially distributed and participatory (Clapp, 2019).

Young people showed a deep interest in the social, political, cultural, and economic issues of their territory, so it is considered necessary, as raised by Espinel-Rubio and Feo-Ardila (2022), "[...] that adults and institutions recognize the agency capacity of young people in the region as transformers of their realities" (p. 64, own translation).

Intercultural dialogue is categorized under La Ceiba, the tree that, for eight months, received, listened to, and protected the bodies they wrote and narrated to build peace (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Members of the creative writing workshop under La Ceiba.

Source: Luisa Fernanda García Guzmán, 2022

Loaded with anecdotes, smiles, and recognition in others and with others, young people recognize that what has been called the social appropriation of knowledge does not result only from the idea of recognizing that there are institutions that arrive, intervene, and leave. Here, as one of the young people said while traveling to Manizales to present the short film, The Unnamable: The Makeup of Reality, "[...] with you we were able to do something, to travel, this is the beginning for many things” (Young personal conversation CORJUP, 2022, own translation). Appropriating their abilities is the capacity left, transited, and exposed; it becomes evident and leaves the clarity that other worlds already exist. In this sense, it can be said that the creative writing workshop constituted for the young people the opening to a journey in which not only the ultimate destination made sense but also the journey taken to reach it.

Conclusions

Posing a question such as, "What would have happened if violence had not reached Ovejas?" from the perspective of the youthful body inheriting the spoken word that names the conflict can also be understood as the opening to a different horizon an option not previously mentioned; a spoken word that inaugurates another perspective, which bets that the future time could be thought of without the necessary mention of the terrifying past. Perhaps creative writing and words that name other optimistic realities can be opportunities for the youth body to value the quota of silence that the previous generation of inhabitants of the Montes de María paid because of violence. Then, that young body can face the needs of the future and the contradictions of trying to live in peace.

In this sense, a sociocultural dialogue around creative writing allows us to transcend stories and practices rooted in family traditions to lead them to narratives that can superimpose nearby realities, the other possible ways of inhabiting the world. Those phrases, situations, and practices that directly influence young people's individual actions are still implanted in their minds.

Therefore, socio-cultural practices invite us to reflect on the body as a system, not only biological but also cultural, that has developed ways of absorbing and internalizing the information, stories, or marks that have passed through the ancestors. They, who from their own lives, bodies, and spirits, occupied a place in the world that positions them as thinking beings, seers, creators, and narrators of their reality and territories. As mentioned in other sections, creative writing is a kind of lucky expression, a way for people to come together, cooperate, and transform themselves and their reality. It is not free for young people to try to transcend the discourse, silence, and self-absorption that result from practices prior to them and that, thanks to creative, artistic, and innovative spaces, position them as builders of their lives.

The creative writing workshop was then assumed to be a space for developing thought, a scenario of shared social learning. It is conducive to putting into practice and strengthening certain cognitive resources such as memory, attention, self-awareness, and problem-solving by enabling a place for creation and thus achieving what was thought impossible; as one of the participants put it, “[…] I never thought I could write”, and the research team witnessed that it was able to do so. This was also a scenario for free expression, to say what you want to say and be what you want to be.

Likewise, the process of creative writing has allowed young people, in Arendt's words, a kind of birth, to emerge in the world, to feel recognized, and to be the main actors who assume themselves as part of the history and the present they are building, not as mere spectators. This workshop has made it possible, as Carmona (2019) would say, for young people to position themselves politically in their community and their context, to assume and be assumed as cognitive subjects with the capacity for agency and with the possibility of contributing to the establishment of a new course of action in the reality of their territory.

References

Aguilera, M. (2013). Montes de María: una subregión de economía campesina y empresarial. Banco de la República- CEER. Documentos de Trabajo Sobre Economía Regional y Urbana, No. 195.https://repositorio.banrep.gov.co/handle/20.500.12134/3033

Alcaldía Municipal de Ovejas. (2020). Plan de Desarrollo Municipal 2020 - 2023. Un gran propósito para renovar Ovejas. Ovejas-Sucre.Gov

Blanco, M. (2012). Autoetnografía: una forma narrativa de generación de conocimientos. Andamios, 9(19), 49-74.https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=62824428004

Capilla, R. M. (2016). Habilidades cognitivas y aprendizaje significativo de la adición y sustracción de fracciones comunes. Cuadernos de Investigación Educativa, 7(2), 49-62. https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=443649571004

Carmona, D. E. (2019). Paisajes de la niñez rural, posicionamientos políticos de niñas y niños de una municipalidad del departamento de Caldas (Doctoral Thesis). Universidad de Manizales, Manizales, Colombia.https://ridum.umanizales.edu.co/xmlui/handle/20.500.12746/4032

Clapp, E. P. (2019). La creatividad como proceso participativo y distribuido: implicación en las aulas. Vol. 149. Narcea Ediciones.

Cobaleda M.D. & Agudelo G. M. G. (2017). La lectura y la escritura. Una dimensión cognitiva. Ánfora, 5(10), 103–112. https://doi.org/10.30854/anf.v5.n10.1997.373

CORJUP, Vanegas, D. & Vidal, K. (2022). Cartilla Didáctica «Narrativas populares para la construcción de Paz». Programa Colombia Científica. Reconstrucción del tejido social en zonas de Postconflicto en Colombia. Editorial Matiz.

Damasio, A. (2005). En busca de Spinoza: neurobiología de la emoción y los sentimientos. Crítica.

De La Ossa Guerra, L. & De La Ossa Guerra, J. (2021). ¿Asociarnos pa’ qué?: aproximación etnográfica a la acción colectiva rural de Ovejas, Sucre. (Caso de los corregimientos de San Rafael y La Peña) (degree project). Universidad de Caldas, Manizales, Colombia.https://repositorio.ucaldas.edu.co/handle/ucaldas/16940

Espinel-Rubio, G.A. & Feo-Ardila, D. (2022). Territorio e identidad de resistencia en jóvenes del Catatumbo (Colombia), constructores de paces imperfectas. Investigación y Desarrollo, 30(1), 40-68.https://doi.org/10.14482/indes.30.1.303.661

Ferrada, J. (2019). Sobre la noción de cuerpo en Maurice Merleau-Ponty. Cinta de Moebio, (65), 159-166. https://dx.doi.org/10.4067/s0717-554x2019000200159

Freire, P. (2004). La importancia de leer y el proceso de liberación. 16a. ed. Siglo XXI.

Limiñana, R. M. (2008). Cuando crear es algo más que un juego: creatividad, fantasía e imaginación en los jóvenes. Cuadernos de la Facultad de Humanidades y Ciencias Sociales (35), 39-43.https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/185/18512511004.pdf

Martínez, M. & Vasco, C. (2011). Sentimientos: encuentro entre la neurobiología y la ética según Antonio Damasio. Revista Colombiana de Bioética, 6(2), 181-194. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/1892/Resumenes/Resumen_189222558012_1.pdf

Méndez, F. (2017). El conflicto armado y la violencia en Ovejas 1997-2007: «Memorias de la guerra» (tesis de maestría). Universidad de Cartagena, Colombia. https://repositorio.unicartagena.edu.co/bitstream/handle/11227/9090/TESIS%20FINAL%20.pdf?sequence=1

Merleau-Ponty, M. (1964). El ojo y el espíritu. Paidós.

Merleau-Ponty, M. (1985). Fenomenología de la percepción. Trad. Jem Cabanes. Planeta.

Mejía, J. M. R. (2014). La educación popular: una construcción colectiva desde el sur y desde abajo. Education Policy Analysis. Archivos Analíticos de Políticas Educativas, 22(62), 1-31.https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=275031898079

Ocampo, A. A. (2011). El contexto educativo y los procesos atencionales: una aproximación desde la cultura, las emociones y el cuerpo. Revista de Educación y Pensamiento, (18), 9-22.https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=3884425

Pousa, V., Pereda, M. & Paniagua, I. M. (2020). Lectura grupoanalítica de un taller de escritura creativa: la escritura como vehículo de interconexión. Revista de la Asociación Española de Neuropsiquiatría, 40(138), 55-66.https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=265065260011

Sánchez-Jiménez, M.H., Rodríguez, Z.E., Loaiza, J. & Rincón, P.N. (2021). Mediaciones Pacifistas. In: Sánchez-Jiménez, M.H., Delgado, L. & Quintero, J. (Editores). Hilando capacidades políticas para las transiciones en los territorios (pp. 93-110). Universidad de Caldas.

Tacca, D. (2016). ¿Cómo aprende el que aprende? La importancia de las emociones en el aprendizaje. Revista Peruana de Psicología y Trabajo Social, 5(1) 53-65. https://es.scribd.com/document/463341046/Como-aprende-el-que-aprende

UARIV. (2021). Boletín Fichas Estadísticas. Ovejas-Sucre. Unidad para las Víctimas.

Valenciano, G. (2019). La metáfora como alternativa metodológica para investigar y reflexionar acerca de la práctica pedagógica en la enseñanza de la lectoescritura. Revista Electrónica Educare, 23(1), 158-180.https://dx.doi.org/10.15359/ree.23-1.9

Vigotsky, L. (1990). Imagination and Creativity in Childhood. Soviet Psychology, 28(1), 84-96.https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.2753/RPO1061-0405280184

Zambrano, L.K., Fuster, D.E., Damian, E. F., Inga, M. G. & Gallardo, C. P. (2019). La imaginación creativa de estudiantes universitarios de la especialidad de Psicología. Apuntes Universitarios. Revista de Investigación, 9(1), 67-78 https://doi.org/10.17162/au.v1i1.350