Public Policies as Mechanisms for Peacebuilding in Territories 1

[English version]

Las políticas públicas como dispositivos para la construcción de paces en los territorios

Políticas públicas como dispositivos para a construção da paz nos territórios

Received 14 October, 2022

Accepted 29 August 2023

|

How to cite López, M. H et al., (2024). Public Policies as Instruments for Peacebuilding in the Territories. Ánfora, 31(57), 222-247. https://doi.org/10.30854/anf.v31.n57.2024.1013 |

Mario Hernán López Becerra2 https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6265-5382 CvLAChttps://scienti.minciencias.gov.co/cvlac/visualizador/generarCurriculoCv.do?cod_rh=0000567752 Colombia Ana María Durango Gómez3 https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0914-1320 CvLAC https://scienti.minciencias.gov.co/cvlac/visualizador/generarCurriculoCv.do?cod_rh=0001650440 Colombia Daniela León Castaño4 https://orcid.org/0009-0002-8767-2506 CvLAC https://scienti.minciencias.gov.co/cvlac/visualizador/generarCurriculoCv.do?cod_rh=0001381844 Colombia

Lorena Delgado Enríquez5 https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2385-4821 CvLAC https://scienti.minciencias.gov.co/cvlac/visualizador/generarCurriculoCv.do?cod_rh=0000018075 Colombia |

Abstract

Objective: To strengthen political capacities for transitions in territories, based on democratic mediations of social conflicts, oriented towards reconciliation and the construction of stable and lasting peace. Methodology: The research was framed within the framework of Research-Action-Participation (IAP), which involved the design, formulation, implementation, and evaluation of processes articulated between communities, public and private institutions, and social organizations, mainly using qualitative methods. Results: This article explores public policies as an ambiguous field of a transdisciplinary nature, and then reviews their connections with concepts such as 'participation,' 'deliberative capacity,' and 'mediation,' assumed as central axes in the formation of public policies. Likewise, it delves into different notions of peace (paces, in a broad sense), which allows us to highlight how different epistemological and methodological conceptions in pacifism determine approaches and devices in social construction. Finally, it examines the links between public policies as devices (strategies) for social mediation, and peacebuilding as a route for the agency of multiple social processes. Conclusions: The central conclusion revolves around the assertion that public policies acquire a peaceful nature insofar as they involve non-violent forms of social interaction. With them, those involved seek to achieve the highest possible level of well-being based on the resources and contexts in which they find themselves.

Key words: Public policies; participation; public deliberation; peace; pacifist mediations (obtained from UNESCO and OIT thesaurus).

Resumen

Objetivo: gestar capacidades políticas para las transiciones en los territorios, con base en mediaciones democráticas de los conflictos sociales, orientadas hacia la reconciliación y la construcción de paz estable y duradera. Metodología: la investigación se enmarcó en la Investigación–Acción–Participación (IAP), lo cual implicó el diseño, formulación, puesta en marcha y evaluación de procesos articulados entre comunidades, instituciones públicas y privadas, y organizaciones sociales, haciendo uso principalmente de métodos cualitativos. Resultados: en este artículo se indaga en las políticas públicas como un campo ambiguo de naturaleza transdisciplinar, para luego revisar sus conexiones con conceptos como ‘participación’, ‘capacidad deliberativa’ y ‘mediación’, asumidos como ejes centrales en la formación de políticas públicas. Asimismo, se profundiza en distintas nociones de paz (paces, en sentido amplio), lo cual permite poner en evidencia cómo distintas concepciones epistemológicas y metodológicas en el pacifismo determinan enfoques y dispositivos en la construcción social. Finalmente, se examinan los vínculos entre las políticas públicas como dispositivos (estrategias) para la mediación social, y la construcción de paz como ruta para el agenciamiento de múltiples procesos sociales. Conclusiones: la conclusión central gira alrededor de la afirmación según la cual, las políticas públicas adquieren una naturaleza pacífica en cuanto involucran formas de interacción social no violentas. Con ellas los involucrados buscan alcanzar el mayor nivel de bienestar posible en función de los recursos y contextos en los cuales se encuentran.

Palabras clave: Políticas públicas; participación; deliberación pública; paces; mediaciones pacifistas (obtenidos del tesauro UNESCO y OIT).

Resumo

Objetivo: desenvolver

capacidades políticas para transições nos territórios, com base em mediações democráticas de conflitos

sociais, orientadas para a reconciliação e a construção de uma paz estável e duradoura. Metodologia:

a

pesquisa foi enquadrada na estrutura da Pesquisa-Ação Participativa (PAR), o que implicou o projeto, a

formulação, a implementação e a avaliação de processos articulados entre comunidades, instituições públicas

e privadas e organizações sociais. Foi empregado principalmente métodos qualitativos Resultados: este

artigo investiga a política pública como um campo ambíguo de natureza transdisciplinar e, em seguida,

analisa suas conexões com conceitos como "participação", "capacidade deliberativa" e "mediação", os quais

são considerados como eixos centrais na formação da política pública. Além disso, explora diferentes

concepções de paz (pazes, em um sentido amplo), permitindo destacar como diferentes abordagens

epistemológicas e metodológicas do pacifismo influenciam as estratégias e dispositivos na construção social.

Por fim, examina os vínculos entre políticas públicas como dispositivos (estratégias) de mediação social e a

construção da paz como um caminho para a agência de múltiplos processos sociais. Conclusões:

a

conclusão central gira em torno da afirmação de que as políticas públicas adquirem uma natureza pacífica na

medida em que envolvem formas não violentas de interação social. Por meio delas, os envolvidos buscam

alcançar o mais alto nível possível de bem-estar, levando em consideração os recursos e os contextos em que

se encontram.

Palavras chave: política pública; participação; deliberação pública; pacificação; mediações de paz (obtidas do tesauro UNESCO e OIT).

Introduction

This article is the result of a systematic process of literature review, as well as theoretical and methodological reflections from a research group and social agency group within the framework of the project «Hilando capacidades políticas para las transiciones en los territorios» (Spinning political capacities for transitions in the territories). The aim was to generate political capacity for transitions in the territories based on democratic mediation of social conflicts towards the stable building and lasting peace. Thus, the project leads to:

[...] subjects acknowledging, on the one hand, their conflicting realities that were attempted to resolve by armed violence and the damage it caused, and on the other hand, the realities of resistance, strategies of healing and mutual care, and the organizations and creations that enabled them to survive and persist as individuals, families, communities, and institutions. (Sánchez-Jiménez et al., 2022, p. 49, own translation).

Project actions are carried out in areas affected by the recent armed conflict in Colombia: The departments and municipalities of Caldas (Samaná and Riosucio); Sucre (Chalán and Ovejas), and Chocó (Riosucio and Bojayá). According to the methodology, this study is framed in the Participation Action Research (PAR) framework that demands to design, formulate, implement and evaluate articulated processes between communities, public and private institutions, and social organizations by qualitative methods, as a contribution to the collective construction of stable building and lasting peace in the territories. RAP demands:

[...] a political commitment to the territory, to the community, and to ourselves; at the same time, it invites us to dialogue and foster democratic practices that strengthen networking, consolidation of identities, and collective work towards peacebuilding. (Sánchez-Jiménez et al., 2022, p. 140, own translation).

The project «Hilandocapacidades políticas» proposes two main routes for research and social agencement: 1) to recognize the damage of armed conflict by more than 50 years, the capacity of individuals, institutions and communities to survive, resist and innovate socially towards the transition to non-violent forms. 2) to strengthen the political capacities of organizations, support public policy (PP) generation, and build proposals with the communities, public institutions, and social leaders to promote democratic transitions towards greater achievements in social, cultural, and political peace in the territories.

One expected result is the design and consolidation of public policies that guide the peaceful transition in the territories. Hence, the importance of addressing the analyses related to concepts, approaches, methodologies, and content of public policies, and their relationship with the construction of several peace experiences and actions. To do this, it is necessary to search theoretically about the issue and propose a reflection to check the categories, and appropriate approaches and designs for the process in the municipalities.

The first part analyzes public policies as an ambiguous field of transdisciplinary nature, then reviews their connections with concepts such as ‘participation’, ‘deliberative capacity’ and ‘mediation’, as central axes in the formulation of public policies. The second part has to do with different concepts of peace (peace, in a broad sense), to highlight how different epistemological and methodological conceptions in pacifism determine approaches and tools in social construction. And the last part analyzes the connection between public policies and territorial peace as the working route.

As a conceptual precision, the concept ‘instrument’ is used in a close sense to Negri’s. (2008). The public policies seen as instruments for peace consist of strategies of resistance, articulation of elements and orientation of practice in frameworks of power. There are collective and individual joints with the design of pacifist resistance instruments to transform conflicts and eradicate violence. The same author states: “[...] thus we subjectivize the power relationships that face the world, the society, institutional decisions and individual practices” (Negri, 2008, p. 45, own translation).

From Government Action to Participation and Collective Impact

After decades of research about public policies, there is no univocal concept that is generally accepted by researchers and policymakers. However, the ambiguity of the concept and its growing connection with the processes of participation, political mobilization, social and citizen impact allow us to identify several relationships with collective peacebuilding processes in the territories affected by the armed conflict in Colombia.

To research further the conceptual and methodological connections, there is a review of PP to the territorial approaches of peace.

An important issue in conceptual ambiguity is stated by Aguilar (2015), the lack of consensus around PPs generates consequences for the concrete identification of actors’ responsibilities, both in the social and political systems. This makes it difficult to distinguish from other type of State intervention instruments, such as programs, laws and projects, among others.

One of the main reasons for the lack of consensus of PPs is the polysemic nature of ‘policy’ and ‘public’, it enables different interpretations and working hypotheses (Rodrigues de Caires, 2018). In Spanish, there are at least three main meanings of 'policy': activities carried out to gain power, the execution of programs by public authorities, and activities related to corporate governance. (Roth, 2002). About the public, it can be understood as something that the private sector conceives as general interest and, therefore, leads through several means. (Aguilar, 1992). The fields of political science, administration, and sociology, among other disciplines, provide definitions that foster the lack of consensus.

The ambiguity in the conception causes that public policy proposals are not to be free from errors, and can be characterized by a certain degree of uncertainty. Under this perspective, on the origin and development of PP discipline, it is necessary to review different researchers who aim to clarify the scope and limitations of the concept. To this end, a review of the main approaches towards transdisciplinary configuration is presented.

Traditionally, much of the PP analysis focuses on the role of government institutions, which actions aim at achieving certain objectives and/or public problems that become public policy. (Montero et al., 2015). Meny and Thoenig (1992), define their study as the action of public authorities within society (p. 7), and consider the means to the results and the expected outcomes of public action.

In a challenging way, some authors believe that not only government action on solving social demands should be considered a public policy. The absence of such actions can also be considered within the definition. A public policy can also be what the government decides to do or not to do (Dye, cite by Ruiz, 1996). Oszlak and O’Donnell (1976) defines it as:

[...] a set of actions and omissions that expresses a particular modality of State intervention in relation to an issue that attracts the attention, interest or mobilization of other actors in civil society. From this intervention, it can be inferred a certain directionality, a certain regulation, that will predictably affect the future of the social process so far developed around the issue. (p. 14, own translation).

Thus, not doing and not making decisions to the social demands and situations as problems has consequences on contexts, actors and their expectations. Some authors ignore or omit the role of other non-state actors in the stages of the public policy cycle. Aguilar (2015) argues that the different definitions should start not only from the nature of the regime but also from the political system, the management of resources, and the mobilization of actors of several types around the needs and demands of the society.

From a broader perspective, this latter researcher gives three definitions that can be summarized as follows: 1. Government action led to social demands, include actors in both the problem and the solution. 2. The orientation of the State through government agencies to fulfil the guarantee of the State purposes and citizens' rights. 3. The result of joint action between the State and non-state actors using budgets and regulations to place a topic on the public agenda.

Another trend for thinking about peacebuilding in Colombia, is presented by Roth (2002), who argues that a public policy is built by the integration of both actions and collective necessary or desirable goals. They are fully or partially addressed by the organization of the Government to generate changes on a problem.

However, the ambiguity of some terms is not the only reason to explain the difficulty of reaching a univocal definition of the concept. In addition, public policies are changing. According to Majone (cited by Torres-Melo & Santander, 2013), public policies have a dynamic-peripheral component, it is made of actions to be changed, such as programs and projects; and a static-core component of ideas, values and other meta-political elements. Thus, according to Torres-Melo and Santander (2013), it justifies the relevance of designing flexible policies that adapt to changes of the population and to social dynamics without forgetting continuity in action.

Another point of interest that obscures these conceptions, is the intervention and interaction of other actors different from state actors in formulating and implementing public policies. It means, the perspectives by private actors and the community as a whole can affect and influence or not the decisions by the State (Oszlak & O’Donnell, 1976). The latter complex the approach to this type of policy, considering that through different instruments, the governments lead their actions to justify the social base and to satisfy the interests of actors holding decision-making power.

Therefore, it must be considered that interaction between actors with particular purposes, and in some opposite cases, should be carried out in the context of cooperation. Tensions arise due to the difficulty of adapting these particularities to the common interest or general welfare, and, therefore, state actors must agree on their strategies to articulate these perspectives to solve the problem. Therefore, state actors become more directors, mediators and articulators than decision-makers within the process. They start from the need to consensus plans and strategies in the management of resources limited for the demands of several types in the interaction among different actors (Torres-Melo y Santander, 2013). There is a definition that covers these parameters that according to public policies can be defined as follows:

[it is] a more or less wide set of actions, decisions and omissions; they generally involve both public and non-public actors; and they respond to situations that are seem as problematic through social and political constructions and therefore, they are listed as issues on the public agenda. (Rodrigues de Caires, 2018, p. 3, own translation).

Velásquez (2009) identifies three types of failures in defining the concept. The first one refers to those that have left out phenomena that could be public policies. Their normative nature should always reach a common goal or interest, and it is not clear if particular interests can take power due to the actors, against the general well-being. The second failure is the unknown or no inclusion of essential elements in the public policies to be seem as government instruments. They do not consider, for example, the goal of policy, the ways to achieve it, the participation of several actors, and processes of dialogue and concertation. The third failure, contrary to the first, focuses on too broad definitions to interpret and classify the instruments, activities and decisions as public policy, that are not, and generate confusion about what public management and other government functions are. Velásquez (2009) proposes an integrating definition to mitigate the confusion and inaccuracies caused by the three types of failures; for the author a public policy is:

An integrated process of decisions, actions, inaction, agreements, and instruments, promoted by public authorities with the eventual participation of individuals to solve or prevent a situation defined as problematic. Public policy is part of a particular context which it nourishes and seeks to modify or maintain. (p. 8, own translation).

While Velásquez’s definition groups together many of the elements that had been left aside by other authors (non-action, the inclusion of non-State actors in the process, the context, etc.), it does not make the appropriate emphasis of citizen participation in public policy making.

In this regard, it is necessary to deepen into the concept of ‘participation’, understood by Nuria Cunill (cited by Pérez, 2019), as the intervention that social agents perform directly in public activities that from bases on rules for interaction, citizenship can be built, and public management can be improved.

Participation can have two approaches: in the management and transformation of conflicts for the tensions between the institution and the actors who demand greater inclusion in decision-making, and the consensus that looks for the implementation of formal and informal mechanisms to promote citizen participation from legislation or political will in many cases generates legitimacy in public management (Pérez, 2019).

Moreover, Holguín (cited by Castillo, 2017) considers that this concept refers to the processes through which citizens are individually or collectively included in decision-making that affect different dimensions, and that can contribute to the human being and collective development. In the same text, Velásquez and González (cited by Castillo, 2017), highlighted the intentional action of one or more actors (directly or indirectly) from their interests and power, to generate changes or maintain the state of the political and social organization. In this area, there are important connections with territorial approaches of interest and peacebuilding.

Certain features of a public participation process can be highlighted, as it was mentioned, is a decision-making process that involves non-governmental actors with some influence. It is planned according to institutional processes and is expected to result in public policies based on social demands and needs. (Baba et al., 2009). As it will be seen, the connection between social demands, advocacy and peacebuilding is at the base of PPs in the territories.

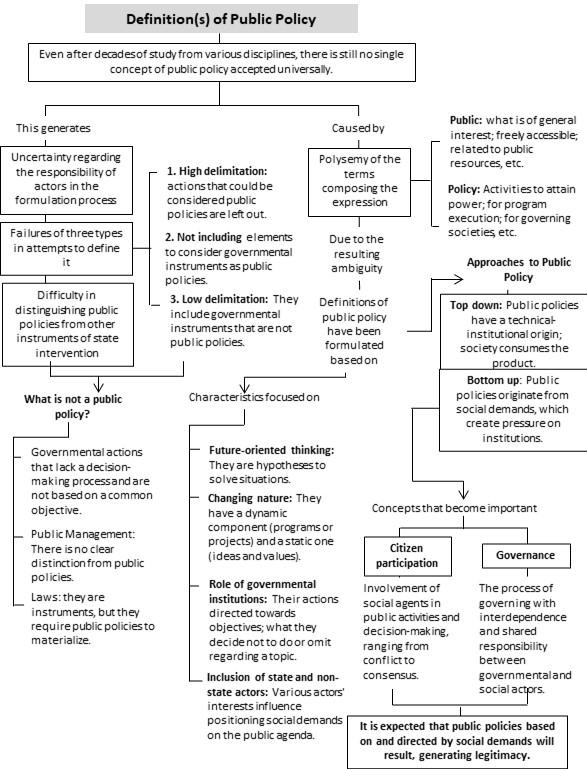

Thus, with the concept of ‘social participation’, and its growing importance in the decision-making process in private and political issues, the public policies overcome the government intervention and involve the explicit consideration of active social actors that differentiate the concept of ‘public action’ (Chac, 2008). The next paragraph will address in more detail the deliberative perspective and the role of trust-building and its connection to participation. The following diagram summarizes the most relevant approaches and statements.

Figure 1. Summary GraphDefinition of Public Policy.

Public Policies Based on Trust, Decision-Making Capacity and Governance

While public policies are often conventionally defined as instruments for guiding public-state action, from other perspectives their role as a social mediator for the regulation, management and non-violent transformation of conflicts is also recognized. Hence, its connection with concepts such as ‘trust’, ‘deliberation’ and ‘governance’, as well as its transdisciplinary connection with communicative rationality, deliberation, argumentation, dialogue, discourses, and narratives, among others.

Trust can emerge from dialogue scenarios and become an articulating factor as a mediator in public policy-making. Brugué et al. (2018), state that doing community-building efforts —and promoting an organizational culture that favors citizenship— empower a common bet. According to these authors, it is necessary to build a double trust: both in the ability of citizens to participate in decision-making and the capacity of people with authority from government to make their own decisions (p. 3). This double condition is expressed in the connection between public authority and citizen participation.

In this way, double trust becomes a basis for collective decision-making: “the predisposition to trust others helps to reduce social complexity and offers a solution to the problem of strangers” (Brugué et al., 2018, p. 17, own translation). In terms of governance, this is a fundamental relationship for building political democracy and the ability to govern effectively. Trust among participants is a key factor in the deployment of deliberation.

While there is a reconceptualization in the political value of trust, public deliberation stands as a powerful strategy for building the common. This is a main practice of participation, in which an idea of the policy is implicit, as French (2016), states, it intends to create conditions of justice from public discussion and the negotiation of interests for the common good. This approach and decision-making capacity of citizens, without ignoring the forces and dynamics involved in the social order and whose analysis, introduces public policies to the fields of the power configuration. According to Barber cited by Chapa (2014), citizenship goes hand in hand with participation, deliberation and community. A citizen who does not participate in the deliberative process generates fake consensus. It is far from unleashing collective capacity for building fair and more democratic societies.

The proposal is for the construction of public policies based on trust, one that strengthens and re-thinks the link between institutions and subjects. For Cruces et al. (2003), the act of trusting implies the creation of a connection; that is, it forces the other subject by the deposited trust. Thus, it is based on the recognition of the other as a legitimate other, as a political subject. It is about repersonalizing the subject, but as a being in “community-unity” that allows to restore the social fabric and weave bridges between the institutions and the world of life.

According to Cruces et al. (2003), trust is not considered as the one produced from faith or “dense truth” (it is given over time by face-to-face interaction) nor as “conformed”, with metaphors created as falsehoods, with rhetorical discourses as an “imitation” of trust. On the contrary, it would start from the assumption of cooperative suspicion, where the relations between institutions and users are viewed as a field of interest; but it is not limited to it, trust is proposed from recognition as a deliberative possibility for the exercise of governance.

In general, two approaches to public policy formulation can be identified: Top down and bottom up. The approach proposed for the project Hilando capacidades políticas para las transiciones en los territorios con la IAP, is articulated with the constructivist perspective (bottom up). PPs have as their starting point social demands and conflicts of interest that generate pressure on the institutions to look for alternatives of collective solution (Chac, 2008).

In the approach of social demands, citizen participation is sine qua non in the formulation, design and implementation of public policies, that provide to the direct or indirect actors, the possibility to influence decision-making and direct the action towards the demand of interests that they consider public, and to improve problematic situations. It is a process of democratic deliberation, at the different stages of the process that looks for the strict balance of technical, instrumental, or institutional characteristic of the prevailing approach.

Public policies, as a collective process, are an essential part of democratic governance. According to Beltramin (2016), governance refers to:

[…] specifically to the procedures that enable the horizontal interaction between the public, private and social actors, in the broader context of an institutionality on large social agreements. (p. 5, own translation).

This essential interaction to the development of good governance can be achieved in participation and impact scenarios through negotiations between various actors. These can also generate networks in processes of policy production, self-government and democracy from the bottom.

According to Aguilar (2007), ⸺in the approach defined by the author as ‘post-govermental governance’⸺ social capabilities are seen useful for the leadership of society, in the face of the government's inadequacy as a leadership agent. Thus, taking into account the current social conditions, the limitations in managerial, technical and financial resources that demand capacities from the goverment and other non-governmental actors. Thereby, governance is understood as a new management process of government, it includes the society in a non-vertical relationship, in a process framed in governability; whereas action must be effective and competent to interdependence between the actors at different levels who will deliberate and have co-responsibility in the process.

For the research purposes of the article, public policies involve actions, omissions, measures, instruments, and strategies of social interaction, that are materialized through the joint action of social and governmental actors (in a decision-making and mobilizing process that involve both participation and influence of several actors), to respond to social demands in several territories and levels of articulation to modify unjust, conflict or problematic situations. This complex and transdisciplinary understanding of public policies enables it to be connected to peacebuilding processes in the territories, as it will be seen below.

Peace and Public Policies: Two Categories in Territorial Dialogue

A main point of departure for clarifying the relationship between public policies as a transdisciplinary field and peacebuilding as a category for the analysis and guidance of social agencement is the differentiation between research for peace and research of peace. For classical authors such as Galtung (2003), the first refers to social science studies focused on values that promote solidarity, cooperation, social fabric and justice, among others. From this perspective, any applied social research that promotes, generates or contemplates the deployment of potential human creators fits within the range of work for peace. The research of peace focuses on human and social constructions that have achieved the highest possible level of well-being, even in conflict and violent contexts. In this latter category, research conducted by pioneering researchers, such as Muñoz and Molina (2004) and Martínez (2000) can be included.

The research phases of and for peace can be traced in several authors. Martínez et al. (2009) and Jiménez (2009) identify and know routes of peace recognized as a field of study due to the political and academic concern for understanding triggering factors of wars during the twentieth century. Jiménez (2009) states:

During the nineteenth century, when war conflicts seem to shape social reality, the concept of peace begins to emerge, but without a theoretical articulation. With World War I and World War II the theory of peace begins to be developed. (p. 148).

The same authors identify three stages or phases in the research of and for peace. The first one was carried out between 1930 and 1959. In epistemological terms, this is a period focused on the deployment of a violent-logical and polemical approach to research the scientific understanding of war. The study focuses on the causes, dynamics, impacts and strategies of wars to avoid analyzing research. Peace (expressed in singular) is associated with the absence of direct violence, its conceptual correlate will be the negative peace, defined by Galtung (2003) as the lack of direct violence.

At the end of the Second World War in 1945, a new international institution was created with the original purpose of recovering the devastated areas by the conflict, and create scenarios for dialogue between states to avoid wars. With the creation of the United Nations and a set of global institutions responsible for driving a version of progress on the prevailing ideologies of economic growth and social modernization processes, public policy agendas were designed to implement mechanisms for the promotion of economic development and modernization. (Escobar, 1996).

During the same period, in Latin America, the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) was responsible for designing and implementing policies that led the creation of developing states. In the same post-war scenario, political and institutional changes took place in a period of international political tensions, social revolutions in the periphery and arms races. In these contexts, social debates, and mobilizations around growing demands for policy for development were decisive in the content of pacifist movements and research.

With the establishment of the Peace Institute in Oslo, Norway, in 1959 studies of peace represented a political breakthrough. The concept of 'positive peace' was introduced, it connected pacifist struggles with the purposes of social justice and the integral development of peoples. The expansion of the meaning of peace constituted a central slogan for the demands of social movements, and announced its potential for the design, formulation, and implementation of public policies to eradicate poverty and transform inequalities that inhibit or constrain human and social capacities.

In the 1990s, fruitful and suggestive transformations in pacifist concepts and practices occurred. In the social science research, there were more frequent studies conducted on cultural and symbolic violence. The growing response dynamics of feminist movements, and multiple demanding expressions from sectors and groups of the population, traditionally excluded or marginalized, expanded the field of research related to violence, conflict and peace. The concept of ‘cultural peace’ achieved international status during the period with the purposes of the United Nations, while the content of peace cultures was expanded in multiple possibilities for work in education and communication.

Perhaps one of the most suggestive approaches in that period is the approach of imperfect peace (Muñoz & Molina, 2004, 2009). The core of the approach is to make an epistemological change apart from research on peace defined as the end of violence. In imperfect peace, making peace involves thinking and acting on the basis of human and social capabilities to regulate and transform conflicts. The non-violent transformation of conflicts (as a feature of life) attracts researchers and communities to the social and political capacities of humans to settle them on the basis of mediation. Under this conception, violence is understood as a type of conflict in which the means are instruments to impose the will and interests of one party, and to sacrifice the well-being of the other.

To control conflicts by non-violent means demands that actors in stressful situations look for the highest possible level of collective well-being (Muñoz and Molina, 2004). In this context, peace unfolds in innumerable fields and possibilities; in several contexts and situations, it is possible to transform conflicts to move towards conditions of political, environmental, interpersonal, internal, social, family, international peace, among others.

In the field of research and social agencement, imperfect peace opens up the possibility of working in peaceful mediation actions to alternatives to territorial conflicts. This enables the implementation of public policies and other social strategies based on local realities and demands, created and expanded by communities and individuals who have developed capacity to make peace in adverse scenarios.

Conflicts, Peace, Public Policies and Territories

Since 2002, in the context of the implementation of the democratic security policy that managed to militarily weaken the guerrillas (along with countless victimizing acts against the civilian population), humanitarian, national, and international organizations have promoted legal frameworks for the state action, humanitarian assistance, and re-establishment of people rights and populations victims of the conflict. Pécaut (2001) identified a feature of paradoxical appearance analyzing the role of the State and the deployment of public policies during the heaviest period of the confrontation:

The armed conflict takes place in rural areas and has not yet reached the cities. There are urban spaces such as Bogotá, where effective public policies aimed at changing living conditions have been pushed forward. (p. 17, own translation).

During the following decade, the military action of the State ⸺implemented within the framework of security policy⸺ and the paramilitary deployment in the territories altered the strength correlations of the armed conflict against guerrilla organizations. The war caused enormous humanitarian costs (forced displacement, kidnappings, confinement, recruitment of children, among other violations of International Humanitarian Law that victimize the civilian population, to more than nine million people). At that time, the current Government the core of the policy was to create security conditions to restore the investor trust, what is known as liberal peace.

In the second decade of the twenty-first century, the national political agenda was reoriented towards the generation of non-violent solutions to armed conflict, through direct dialogue and the signing of a peace agreement between an insurgent sector and the government of President Juan Manuel Santos (2010-2018). The national public policy agenda was substantially modified with initial steps towards the implementation of the agreement content. One criticism of the process has been the low involvement of territorial actors in the design and formulation of agreements.

At the end of the government of Juan Manuel Santos, and the possession of Ivan Duque as President supported by the most critical political sector of the peace process, the government policy was directed at introducing adjustments and changes in the content and scope of the agreements. However, uncertainty and widespread crispation in Colombian society, and the relationship between peacebuilding and public policies with territorial approaches has oriented to the action of organizations, institutions and communities committed to create different life alternatives.

After the signing of Peace Agreements in 2016, between the national government and FARC-EP, there have been fractures, leaps and continuity in the transitional processes. At the same time, in some regions and territories such as El Chocó, Bajo Cauca, Arauca, South East and Catatumbo, the armed conflict over the control of legal and illegal economies has intensified. In municipalities in Montes de María, and in other regions of the Caribbean and the south-east of the country, dynamics of expanding paramilitary control and armed conflict between different armed structures are present.

The design, formulation, and implementation of public policies for peace involves recognizing different transitional processes (continuities, leaps and fractures), and different state agency group, community, national and international agencies that must be recognized and coordinated. Nowadays in Colombia, the relationship between public policies and peacebuilding with a territorial approach is the subject of academic debates and different analyses that can still be considered as preliminary. Some work paths are found in the relationships between peacebuilding social processes and local-solidarial governance strategies; such strategies are based on the generation of political capacities based on individual and community potential.

Consequently, the territorial approach of public policies in several transitional processes implies assuming PPs as useful instruments for the generation of other realities, understanding the differential causes and implications of armed conflict, and the subjective, institutional and community potential for peacebuilding. In this regard, political capacities (organization, interlocution, resistance, non-violent transformation of conflicts and social leadership, among others) are the drivers of collective work that promote peaceful management and transformation of conflicts in territories affected by armed conflict, and the eradication of structural violence and other conflicts during the transition.

One main issue for the territorial peacebuilding on getting human and social responses ⸺as alternatives to the conflict⸺ can grow, multiply and sustain over time through the implementation of active policies that generate public value and base democratic practices; such as the generation of new institutions, social impact, empowerment, public-community coordination and public deliberation.

Methodological Framework for Research in the Territories

While the territories have suffered huge humanitarian impacts from armed conflict (it must remain a research topic and intervention to stop and prevent it), it is also necessary to coordinate and implement work agendas to support, communicate and strengthen resistance processes and collective experiences of non-violent conflict transformations.

From a methodological point of view, research towards the recognition of peacemaking capabilities in territories can be supported by a design that integrates components of the public policy cycle, and elements of the routes designed in the work focused on imperfect peace. As an example, López (2013), proposes a methodological process into four phases that can be adapted as follows:

1. Conflict recognition: For research it is essential that participants characterize, debate, examine and understand territorial conflict. It is about recognizing the roots of conflicts, their actors, interpretations and actions. This involves the generation of knowledge dialogues and collaborative research processes involving multiple governmental, institutional and community actors.

2. Strengthening mediation: Mediation plays a main role in peacebuilding and cultivation of peace, when it comes to people, organizations and institutions that have expanded social and political capacities to understand and transform their conflicting realities. Mediators are constructors of other realities often use several social skills that contribute to the transformation of conflicts and provide countless learnings for public policy.

3. Recognition of peace experiences: A main issue in the imperfect peace approach lies in supporting public policies for peace in the territories, from the transformative experiences of communities and social organizations. The systematization approaches and methods used by social researchers can support communities and organizations in generating strategies to expand their policy capabilities.

4. Expanding policy capacities: The territorial peacebuilding demands to understand the conflict, recognize the capacities, and to broad the possibilities of collective political action. These capabilities involve the generation of leadership in democratic territories, trust, organization, and design of routes for the positive transformation of conflicts based on lively public policies.

Final Discussion

At a level of normative formulation, public policies can be thought and implemented as “[...] a set of actors and institutions that shape the development of the territory” (Eslava, 2011, p. 24, own translation). In the field of social agencement, PPs could be considered expressions of agreements and disagreements that, in their heterogeneity, manage to be generators of collective values to positively transformations of conflicts. The opposing interests in the policy-making process indicates that there is a matter of tension and controversy and that can be regulated or transformed in a peaceful way.

As communicative strategies for mediating social conflicts, public policies adopt a peaceful nature. As they involve forms of interaction in which participants look for the highest level of well-being depending on their own resources and contexts (Muñoz & Molina, 2004).

In the project «Hilando capacidades políticas para las transiciones en los territorios», three dimensions can be identified in which public policies are twined with peacebuilding with a territorial approach:

1. Public policies, understood as useful instruments for social mediation processes, make sense to the extent that, as Berlin (2010) warns, policy is essentially a conflict of means, ends and interests. In this case, the media are not technical instruments, they build and expand actions for the generation of trust, capacity for deliberation, social and political impact.

2. The project «Hilando capacidades políticas para las transiciones en los territorios» carries out its actions in scenarios that have been or are hurt by the recent armed conflict. These are municipalities in which governmental political management is determined by clientelism processes, apparent and ineffective ways of citizen participation and involvement, founded distrust in the institutions and multiple expressions of old and new inequalities that involve developing the project with a sense of political reality.

In the framework of conflicts and multiple violences of the territories «Hilando Capacidades» considers the organization actions, men and women leaders, and several community and institutional actors ⸺in countless processes of collective resistance to violence, and in social innovation processes to transform adversities and regulate social, economic, cultural and environmental tensions⸺ to turn public policy approaches on the needs of individuals towards public policies based on collective potential achievements.

3. If the public policy cycle is understood as a set of policies and management operations useful for the collective construction or reconstruction of territories, it can be said that each of the phases of the cycle is, at the same time, a methodological route, and a space for conflict resolution learning. As literature states:

The positive notion of conflicts allows us to define them as situations of change to the overcoming of tensions and the creation of new objectives to future relationships. (Paris, 2009, p. 31, own translation).

In the territories in which the actions of «Hilando Capacidades» are carried out, the positive notion of conflict involves two tasks. The first involves alternatives based on dialogue, reconciliation and reconstruction of human relations to face the conflicts between radicalized actors. The second must be oriented towards supporting and co-creating spaces and processes to contribute to the transformation of conditions of injustice, inequality and lack of substantive democracy. This involves expanding collaborative education processes based on knowledge dialogues with participants.

The growing interest in the evaluation of public policies, the analysis of the performance of institutions and the active state action based on citizen incidence are relatively recent concerns in Colombia. It has become apparent in the context of the State reforms in the 80s, and with the adoption of the new Political Charter in 1991.

While civil society organizations have been driving public policies for human rights for years, it can be said that the community and institutional interest in linking public policies with territorial peacebuilding is much more recent. These initiatives largely arise from the agreements signed between the National Government and an armed insurgency sector in 2016.

References

Aguilar, L. F. (1992). Estudio introductorio y Edición. El estudio de la Políticas Públicas. Colección Antologías de Política Pública.

Aguilar, L. F, (2007). El aporte de la política pública y de la nueva gestión pública a la gobernanza. Revista Del CLAD Reforma y Democracia, 39, 5-32. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/3575/357533693001.pdf

Aguilar, L. F. (2015). El concepto de política pública. En J. I. Cuervo (Ed.), Ensayos sobre políticas públicas II (pp. 35-86). Universidad Externado de Colombia.

Baba, C., Cherecheş, R., Mora, C., & Ţiclău, T. (2009). Public Participation in Public Policy Process-case Study in Seven Counties from North-western Region of Romania. Transylvanian Review of Administrative Sciences, 26, 5-13.https://rtsa.ro/tras/index.php/tras/article/viewFile/199/195

Beltramin, J. B. (2016). Around the Sense of Governability and Governance: Definition and Scope. Revista Internacional de Filosofía, 67, 149–162. https://revistas.um.es/daimon/article/view/202011/191031

Berlin, I. (2010). Dos conceptos de libertad y otros escritos. Alianza.

Brugué, Q., Gelis, J. F. & Güemes, C. (2018). Confianza democrática y proceso de formulación de políticas públicas: el caso de la política hídrica de Cataluña. Revista de Sociología e Política, 26(67), 129–152.https://doi.org/10.1590/1678987318266707

Castillo, M. (2017). El papel de la participación ciudadana en las políticas públicas urbanas, bajo el actual escenario de la gobernanza. Revista CS, 23, 157–180. https://doi.org/10.18046/recs.i23.2281

Chac, M. C. (2008). Gobernanza y participación ciudadana en las políticas públicas frente al reto del desarrollo. Política y Cultura, 30, 9–37.https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=26711160002

Chapa L. A. (2014). El retorno a la política Incertidumbre, deliberación y acción política en la teoría de la democracia de Benjamin R. Barber. Veritas, (31), 31-47. https://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0718-92732014000200002

Cruces, F., Díaz de Rada, Á., Velasco, H., Fernández, R., Jiménez de Madariaga, C. & Sánchez Molina, R. (2003). ¿Confianza, cosmética o sospecha? Una etnografía multisituada de las relaciones entre instituciones y usuarios en seis sistemas expertos en España. Alteridades, 13(25), 77-90. https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=74702508

Escobar, A. (1996). La invención del tercer mundo. Construcción y deconstrucción del desarrollo. Norma.

Eslava. A. (2011). El juego de las políticas públicas. Reglas y decisiones sociales. Universidad EAFIT.

Francés, F. J. (2016). La interacción deliberativa en los procesos de participación vinculados a las decisiones públicas. Revista de Sociología, 102(1), 53-72. https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/papers.2149

Galtung, J. (2003). Paz por medios pacíficos. Paz y conflicto, desarrollo y civilización. Gernika Gogoratuz.

Jiménez, F. (2009). Hacia un paradigma pacífico: la paz neutra. Revista de Ciencias Sociales, 16, 141-189. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/105/10512244007.pdf

López, M. H. (2013). Concepciones y enfoques de políticas públicas para transformar la crisis cafetera en el departamento de Caldas –Colombia– como parte de una agenda para la paz positiva e imperfecta (tesis de doctorado). Universidad de Granada, Spain.https://digibug.ugr.es/bitstream/handle/10481/30791/21946541.pdf?sequence=1

Martínez, V. (2000). Saber hacer las paces. Epistemologías de los estudios para la paz. Convergencia, Revista de Ciencias Sociales, 7(23), 49-96.https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/105/10502303.pdf

Martínez, V., Comins, I. & Paris, A. (2009). La nueva agenda de la filosofía para el siglo XXI: los estudios para la paz. Convergencia, 16, 91-114.https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/105/10512244005.pdf

Meny, Y. & Thoenig, J.-C. (1992). Las Políticas Públicas. (A. S.A, ed.).

Montero, L. A., Herrera, Á. & Abril, L. (2015). Análisis comparado de las políticas públicas de defensa de México y Brasil. Retos de una nueva contrainsurgencia. Papel Político, 19(2), 631-655.https://doi.org/10.11144/javeriana.papo19-2.acpp

Muñoz, F & Molina (Eds.). (2004). Manual de paz y conflictos. Universidad de Granada.

Muñoz, F. & Molina, B. (Eds.). (2009). PAX ORBIS. Complejidad y conflictividad de la paz. Universidad de Granada.

Negri, A. (2008). La fábrica de porcelana: Una nueva gramática de la política. Paidós.

Oszlak, O. & O’Donnell. G. (1976). Estado y políticas estatales en América Latina: hacia una estrategia de investigación. CLACSO. https://repositorio.cedes.org/handle/123456789/3332

Paris. S. (2009). Filosofía de los conflictos. Una teoría para su transformación pacífica. Icaria.

Pécaut, D. (2001). Guerra contra la sociedad. Editorial Planeta.

Pérez, M. E. (2019). La participación ciudadana de los movimientos socioambientales en América Latina. Rev. Colomb. Soc, 42(1), 135–156.https://doi.org/10.15446/rcs.v42n1.73023

Rodrigues de Caires, C. M. (2018). Políticas públicas: bases conceptuales, evolución y actuales desafíos. Universidad Central de Venezuela.

Roth, A.N. (2002). Políticas públicas: formulación, implementación y evaluación. Ediciones Auroras.

Ruiz, C. (1996). Manual para la elaboración de políticas públicas. Plaza y Valdés.

Sánchez-Jiménez, M. H., Delgado, L. P., Quintero, J. A., Lugo, N. V., Pinilla, V., López, M. H., Cifuentes, M. R., Hurtado, D., Rodríguez, Z. E., Loaiza, J., León, D., Salazar, M., Buitrago, J., González, G. A., Arango, L. J., Conto, B., Sánchez, R., Bonilla, F., Sánchez A. M. & Rincón, P. N. (2022). Hilando capacidades políticas para las transiciones en los territorios. Fundamentos epistemológicos, teóricos y metodológicos. Editorial Universidad de Caldas, programa Reconstrucción del Tejido Social en Zonas de Posconflicto en Colombia.

Torres-Melo, J. & Santander, J. (2013). Introducción a las políticas públicas: conceptos y herramientas desde la relación entre Estado y ciudadanía. IEMP Ediciones.

Velásquez, R. (2009). Hacia una nueva definición del concepto política pública. Desafíos, 20, 149–187. https://revistas.urosario.edu.co/index.php/desafios/article/view/433